Joint discovery

David Plunkert

A study of joint pain has opened up a new route to treatments that could stop the inexorable advance of osteoarthritis, which affects 30 percent of people over age 60.

“People in the field predominantly view osteoarthritis as a matter of simple wear and tear, like tires gradually wearing out on a car,” says associate professor of immunology and rheumatology William Robinson, MD, PhD, who published the study in the December 2011 issue of Nature Medicine. It also is commonly associated with blow-outs, he adds, such as a tear in the meniscus or some other traumatic damage to a joint.

But researchers noticed that inflammatory cells and some of the substances they secrete were higher than normal in osteoarthritic joint tissues, even before symptoms were evident. That got Robinson and his co-authors thinking that inflammation might be a driver, rather than a consequence, of the disease.

Their new study showed that, indeed, initial damage to the joint starts a chain of molecular events that escalates into an inflammatory attack on the damaged joint by one of the body’s key defense systems against bacterial and viral infections, the so-called complement system. This sequence of events triggers a chain reaction called the “complement cascade,” and it begins early in the development of osteoarthritis.

Drugs thwarting inflammation induced by the complement system may someday prove useful in preventing the onset of osteoarthritis after an injury, says Robinson, a staff physician with the Veterans Affairs Palo Alto Health Care System. Toward that end, he has begun a pilot study of the effects on osteoarthritis of an anti-inflammatory drug that’s already available. — Bruce Goldman

Anthrax variations

Stanford researchers have discovered that people vary widely in their sensitivity to the anthrax toxin, which could explain why some weather infection by the deadly bacterium Bacillus anthracis with no symptoms.

Their study, which looked at blood cells collected from 234 people, found that cells of three people were virtually insensitive to the toxin, while the cells of some were hundreds of times more sensitive than those of others.

The study was published Feb. 21 in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

More in Inside Stanford Medicine. — Krista Conger

Log on

David Malan

Think of it as Facebook for Stanford‘s medical minds. The School of Medicine now has a social network of its own. The school’s information technology team believes it’s the first fully deployed social network at any U.S. academic medical center.

The network, launched in October, combines the medical school’s Community Academic Profiles system, known as CAP, with a collaboration platform that allows users to share status updates, customize profiles, follow colleagues, form groups, share documents and even find research collaborators and mentors. CAP Network provides full profiles for all students, faculty and staff at the School of Medicine, bringing the total number of individuals in the system to nearly 10,000. So far, about half of the group’s members have activated their accounts.

“The users of CAP Network will be bound by a ‘social-networking honor code,’ based on university policies,” says Henry Lowe, MD, senior associate dean for information resources and technology. “Operating within that framework, we leave it to the community to decide how they want to use CAP Network on a day-to-day basis. It should be interesting to see how they use the platform.” — John Stafford

Women feel more pain?

Women report more intense pain than men in virtually every disease category, according to Stanford investigators who mined a huge collection of electronic medical records — 160,000 pain scores reported for more than 72,000 adult patients.

“We saw higher pain scores for female patients practically across the board,” says Atul Butte, MD, PhD, the senior author of the study, published in the March Journal of Pain.

“In many cases, the reported difference approached a full point on a 1-to-10 scale. How big is that? A pain-score improvement of one point is what researchers view as indicating that a pain medication is working.”

However, it’s not clear that women actually feel more pain than men do, says Butte. “But they’re certainly reporting more pain than men do. We don’t know why. But it’s not just a few diseases here and there, it’s a bunch of them — in fact, it may well turn out to be all of them. No matter what the disease, women appear to report more intense levels of pain than men do.” — Bruce Goldman

Computing cancer

David Plunkert

Since 1928, the way breast cancer characteristics are evaluated and categorized has remained largely unchanged. It is done by hand, under a microscope. Pathologists examine the tumors and score them according to a scale first developed eight decades ago. These scores help assess the type and severity of the cancer and calculate the patient’s prognosis and course of treatment.

Now computer scientists and pathologists at Stanford have trained computers to analyze breast cancer microscopic images better than humans can. They report this in the Nov. 9, 2011, issue of Science Translational Medicine.

Humans, in the form of pathologists, use three specific features to evaluate breast cancer cells — what percentage of the tumor is comprised of tube-like cells, the diversity of the nuclei in the tumor’s outermost cells, and the frequency with which those cells divide.

On the other hand, the program, called C-Path, assesses 6,642 cellular factors to reach its conclusions. C-Path yielded results that were a statistically significant improvement over human-based evaluation.

“We’re looking at a future where computers and humans collaborate to improve results for patients across the world,” says Matt van de Rijn, MD, PhD, a professor of pathology and co-author of the study. The study’s lead author was Andrew Beck, MD, a doctoral candidate in biomedical informatics. — Andrew Myers

Historic trial halted

David Plunkert

“Spending Persian New Year with family. I can’t complain. I’m alive, relatively healthy, and loved :),” tweets 23-year-old Katie Sharify in March, four months after she became the fifth and final participant in a study of an embryonic-stem-cell-derived treatment for severe spinal cord injury.

Sharify, paralyzed from the waist down in a car accident, learned on Nov. 14, 2011 — just two days before her treatment — that the multisite trial’s sponsor, Geron Corp., was ending the trial early for financial reasons. They had initially planned to enroll eight to 10 patients.

“At that point I felt very let down and didn’t know if I wanted to go forward with the procedure,” recalled Sharify in a December interview. “But then I decided that five patients were still better than four, and that I could still have some sort of an impact.”

Stanford’s chair of neurosurgery, Gary Steinberg, MD, PhD, performed the procedure at Santa Clara Valley Medical Center on Nov. 16.

The Geron trial was the first to implant cells derived from human embryonic stem cells into human patients. As a trial participant (the second at Stanford), Sharify received an injection of about 2 million specialized cells to the injured area of her spinal cord. The cells, oligodendrocyte precursors, had been coaxed to develop from human embryonic stem cells. Damage to the sheath of oligodendrocyte cells that normally wraps nerve cells is a common cause of paralysis. The trial was the first phase of an effort to see whether the cells could repair the damage. The patients will be monitored for the next 15 years, according to the company.

The trial’s end is a disappointment but not a calamity, says Steinberg. “We should remember that five of the anticipated eight total patients were successfully transplanted with no adverse effects noted to date. Since this was designed as a safety study, the outcomes are very encouraging.” — Krista Conger

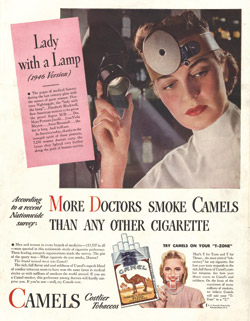

Blowing smoke

Robert Jackler

Tobacco companies conducted a decades-long campaign to manipulate throat doctors into calming the public’s concerns that smoking harmed health, according to a new study by Stanford researchers. Starting in the 1920s, this campaign continued for over half of a century.

“The companies successfully influenced these physicians not only to promote the notion that smoking was healthful, but actually to recommend it as a treatment for throat irritation,” says the study’s senior author, Robert Jackler, MD, professor and chair of otolaryngology.

Jackler and co-author Hussein Samji, MD, published the study in January’s The Laryngoscope. — Tracie White

More from Jackler about physicians working for Big Tobacco on Stanford’s 1:2:1 Podcast

Twins separated

Ginady Sabuco has to run to keep up with her twin toddlers, Angelina and Angelica, who are racing around a San Jose, Calif., park in opposite directions.

She’s not complaining, though.

The girls, now 2 1/2, were born joined at the chest and abdomen with fused livers, diaphragms and breast bones. The chance for them to grow up as individuals is a dream come true, she says.

During a 10-hour surgery at Lucile Packard Children’s Hospital on Nov. 1, 2011, the twins’ sternums were completely removed and reconstructed with resorbable plates that will gradually dissolve as the bones take over.

Recovery was faster than expected, with the girls going home Nov. 15 and walking independently less than a week later. Their balance and strength have continued to improve.

The girls have distinct personalities: Angelina is quiet, Angelica more talkative. They still love playing together and wearing matching dresses, but as their happy parents are discovering, they also like exploring on their own. — Erin Digitale