Special Report

Sleuth of the mind

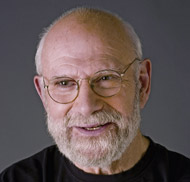

A conversation with Oliver Sacks

Illustration by Joe Ciardiello

Oliver Sacks has opened the eyes of the world to neurological maladies that defy easy medical explanations. In his practice as a general neurologist, patients mistake their wives for hats, long- dormant minds inexplicably recover consciousness and rare brain disorders afflict individuals out of nowhere.

In his latest book, The Mind’s Eye, Sacks writes of a variety of visual abnormalities that stem from neurological accidents. Besides detailing the unusual nature of these disorders, Sacks unveils the miraculous ways that human beings often adapt and compensate for their illness. He also writes of confronting his own neurological malady, a condition known as prosopagnosia or face blindness. And he describes how he has coped since experiencing a radical change in his vision seven years ago.

Diagnosed with ocular melanoma in 2005, Sacks has lost vision in his right eye along with the ability to see in three dimensions, a sad irony for someone who has long been a member of the New York Stereoscopic Society. He works surrounded by blown-up copies of documents and magnifying glasses, putting the final touches on his next book, which will be about hallucinations. The Columbia University Medical Center physician continues to see patients and still swims every day. He spoke with Paul Costello, chief communications officer for the School of Medicine, who gets the sense from talking with him that he’s always swimming upstream.

Costello: In The Mind’s Eye, people surmount incredible challenges: an art dealer whose strokes leave her without language but is still able to communicate, a novelist who loses his ability to read but not to write. They seem almost superhuman, with great courage and unusual perceptual skills. Does coping with neurological problems hone survival instincts?

Sacks: Well, it can. I think any disadvantage can. What do they say, what doesn’t kill one strengthens one? But I may be guilty of some selection in writing about people who have one way or another dealt with or transcended their conditions, rather than being beaten down by them. Obviously, in real life, one sees both.

Costello: The people you write about compensate in many ways. What do we know about the biological basis of compensation?

Sacks: Living organisms will find ways of accommodating to adverse circumstances. With bacteria, it’s sort of genetic. In a few generations, you’ll find bacteria that can get nourished by an antibiotic that would have killed them 20 generations earlier. But in the individual, there’s this tremendous power to go on regardless, even if you break a leg on a mountain and no one else is there.

But in particular, the brain is enormously resourceful and has all sorts of tricks up its sleeve. For example, the Canadian novelist who became unable to read: He started to read again and wondered if his brain was healing. It turned out he was still visually totally unable to read, but unconsciously he had started to move a finger and then his tongue [on the roof of his mouth], copying what he read. Since, in this condition, one can write even though one can’t read, he was in effect reading by writing with his tongue. That sounds weird and wild, but...

Costello: It does. It sounds so wild.

Sacks: But it worked. There was one point at which he bit his tongue and it got sore and swollen and he said he couldn’t read for two weeks because of his tongue.

Costello: Would you talk more about the plasticity of the brain?

Sacks: First, one needs to say that the brain and nervous system in general has more ability to recover and even generate new nerve cells than some of us realized. But also there’s this capacity to develop new paths in the existing machinery. I encourage patients to explore this and to try to do things a different way — although, they often discover this for themselves. I will say to patients, “I’m not sure that I can cure you or I can help this directly. But let’s think about other ways of living, other ways of doing things, and think positive.”

Costello: When you lost vision in your eye, you began having hallucinations. Do you still have them?

Sacks: Oh, I do. If I sit here and look up at the ceiling, it is covered with what look like runes or hieroglyphics. They vaguely resemble English letters or numbers or Greek letters. But I’m used to that, as I’m used to my tinnitus hissing in my ears, and I pay no attention to it.

Costello: I read that your vision loss also led to a loss of stereovision. How are you coping with everything looking two-dimensional instead of 3D now?

Sacks: I was rather dangerous pouring wine or tea for some people because I would miss the glass and pour it into their lap. Sometimes, when shaking hands, my hand would miss their hand by a foot or so. I think I’ve become more skillful at making judgments with one eye. I mean, people who lose an eye early can become ball players and aviators. In one’s late 70s, you don’t adapt so easily. I’ve had particular dangers going down stairs, and I will hold a rail or I will count, I will feel for the next step with my toe. But even so, I may have an overwhelming sense that there isn’t another step, so I have to learn to disbelieve my eyes.

Costello: You also write about your face blindness. How did you come to realize that was a disorder?

Sacks: I don’t think that was until I was an adult and met my brother in Australia whom I hadn’t seen for 35 years. He was also quite unable to recognize faces, including his own, and places. Then, after I published The Man Who Mistook His Wife for a Hat, I got many, many letters from people saying they’d had this sort of thing all their lives and it was often in the family. At that point I realized that this must be something quite common, but almost never discussed. I think one of my reasons for writing is to open up a subject so it can be discussed.

Costello: When I read reviews of your new book, critics wrote first and foremost about survival and compensation and less so about the individual disorders. Is facing adversity what you want people to focus on?

Sacks: Well, yes, I think survival is my theme, but I can only explore the theme in a highly specific way. I think both impulses are there. There’s a great physician, William Osler, who once said, “To talk of diseases is a sort of Arabian Nights entertainment,” which sounds like a hideous thing to say. But there is something very interesting about what happens to people, and that’s also very frightening. It’s also inspiring to know how people deal with it.

This interview was condensed and edited by Rosanne Spector.

1:2:1 Oliver Sacks

Listen to the interview.

Photo by Elena Seibert