SPRING 2009 CONTENTS

Home

The demonization of immunization

Shots get the once-over

What is a vaccine?

Immunization demystified

Asking How

Vaccine Side Effects Probed

When science gets hijacked

NBC News chief medical editor tells why she broke her silence

Insourced to India

A vaccine for a scourge of the developing world

Peet’s passion

The medical education of Amanda Peet

Field yields

Can genetically engineered plants provide vaccines?

Shoot it, donít smoke it

An injectable tobacco-grown vaccine

Golden needles

Vaccines for seniors

Grow up

Can vaccines built for kids work in older immune systems too?

Insourced

to India

A Vaccine for a scourge of the developing world

By Tracie White

Illustration by Matt Bandsuch

Each night, the young pediatrician entered a battle zone. Babies — 50, 60, sometimes 70 babies — limp from dehydration due to days of vomiting and diarrhea, filled the pediatric ward at the largest public hospital in India. Some were unconscious, many hovered near death.

Many were malnourished babies from poor families who had traveled long distances at great expense to get to New Delhi’s All India Institute of Medical Sciences, considered an oasis for India’s poorest. Many others, with no transportation, died at home. Rotavirus was the primary cause of the dehydration. It’s an infection easily contracted and easily treated, but deadly without proper care.

“I remember nights putting IV drips to treat the dehydration in the first baby beginning at 9 p.m. and not finishing with the last baby until 6 in the morning,” says M.K. Bhan, MD, looking back 30 years or so to his residency days. “There were that many babies. I can’t describe it to you. It was like a bazaar. I realized at the time, this is madness. This is utter chaos.”

Now Bhan serves as India’s secretary of biotechnology and battles health-care shortfalls throughout the country, home to a third of the world’s poor. And his confrontation with rotavirus continues.

Trujillo-Paumier

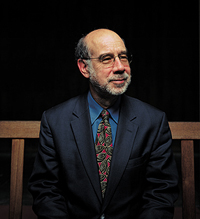

Harry Greenberg, MD

Worldwide, the rotavirus kills half a million children annually, a third of those in India. Improved hygiene and cleaner water don’t stop the virus. It infects all children across the globe but it’s most deadly in developing countries where malnourished children, poorly educated parents and limited medical care create a recipe for disaster. In India, where 25 million children are born each year and nearly half of all children are clinically malnourished, it’s no surprise rotavirus continues to be a public-health nightmare.

The solution is simple. Indian babies need an affordable vaccine. The United States, where only 20 children die each year from rotavirus, has two rotavirus vaccines on the market. But immunization with these runs nearly $200 per child — far too much for India, which needs a vaccine priced at less than $2 a dose, says Bhan.

Could the nightmare be ending? One team of researchers dares to hope that its rotavirus vaccine has a shot. After years of testing in the lab, collaboration across time zones and intense training of scientists at a small Indian biotech firm, the vaccine is ready to begin large-scale testing.

“The goal is to market a rotavirus vaccine that is developed, tested and manufactured in India that will not only be effective in India, it will be affordable,” says Harry Greenberg, MD, the Joseph D. Grant Professor of Medicine and Microbiology and Immunology at Stanford, who with Bhan is one of the research collaborators. “It’s an amazing experiment.” It would also be the first vaccine developed in India in at least 100 years.

“The goal is to market a rotavirus vaccine that is developed, tested and manufactured in India.” — Harry Greenberg

The global team includes scientists and health-care experts at Stanford, the National Institutes of Health, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, the Seattle-based nonprofit PATH, the government of India’s department of biotechnology, the Indian Council of Medical Research, and multiple Indian public health agencies. Its product could be on the market within three years.

Not only could the vaccine save tens of thousands of lives, it could become a model program for how to create vaccines within the developing world to be distributed first to the children who need them most.

The seeds

Setting out to create a vaccine is never a slam dunk. Part scientific calculation, part leap of faith, it takes skill, knowledge, luck and good timing. Not to mention a steady infusion of cash, which explains why most vaccines are developed in the West where there’s more advanced technology and more money.

“It’s an incredibly risky endeavor,” says George Curlin, MD, who became a supporter of the India vaccine project early on in the process. He’s now at the NIH where he helps oversee vaccine clinical trials. “It’s an industry characterized by failure. Only 10 percent of bright ideas even make it into a clinic for study. Fewer still make it into some kid’s arm.”

The story begins with a scientific discovery. The idea for the India vaccine first germinated back in the mid-1980s, when two different groups of scientists working in India discovered unusual strains of the rotavirus, which infected newborns in hospital nurseries without making them sick. Bhan happened to be among the scientists at the All India Institute of Medical Sciences who discovered one of these strains during routine testing of newborns. He recruited Roger Glass, MD, PhD, a diarrheal expert, to join in the study of the strain. About the same time, another scientist, Durga Rao, MD, contacted Stanford’s Greenberg, a rotavirus and vaccine expert, to collaborate on a similar discovery in newborns in Bangalore. The two groups were originally competitors that became collaborators.

“The strains were really like natural vaccines,” says Glass, director of the NIH Fogarty International Center. “We realized that the nursery strains could be vaccine candidates for India.”

Early testing showed that both strains were human-bovine gene reassortments — that is, they were viruses that contained genetic components from both human and bovine rotavirus strains. This might explain why they caused no symptoms. The troublesome portions of the human virus had been exchanged with a rotavirus that usually infects only cows. The switch robbed the virus of its ability to wreak intestinal havoc in humans.

The plan was to use these naturally occurring, weakened strains to develop a vaccine for babies that would give them exposure without symptoms. The researchers would follow the usual logic of vaccine development but had the added benefit of a naturally occurring gene reassortment that they didn’t have to make themselves. This could save both time and money.

Now all they had to do was develop the vaccine and test it several times in thousands of babies at an incredibly low cost so that it would be affordable in India.

One step forward…

From the beginning, the vaccine plan was a collaborative effort, which was both challenging and key to its success so far, collaborators say.

“Working like a family, all investigators and agencies stayed connected through monthly conference calls, periodic meetings, e-mails and negotiations with as many as six institutional review boards, which was at times a nightmare,” writes Nita Bhandari in an e-mail. Bhandari, PhD, has been the Indian scientist responsible for conducting clinical trials initially through AIIMS and then through the Society for Applied Studies in India, a nonprofit that she now co-directs. “At the same time, the togetherness, working for a purpose across the globe was inspiring.”

Early on, major defense contractor DynCorp produced a pilot lot of the two vaccines for clinical testing. When the New Delhi strain of the virus provided the greatest immunity to the disease, the team decided to move forward with only this variant. Although his variant wasn’t chosen, Greenberg continued with the team, committed to its goal of producing a safe, effective and affordable vaccine for India.

In the late 1990s, the project stalled. Funding had run out. About the same time, the first-ever rotavirus vaccine had entered the U.S. market, which seemed to reduce the urgency of the India team’s mission. The 1998 release of Wyeth’s RotaShield vaccine in the United States, which Greenberg also helped develop, met with initial success. But a year later, the company recalled it when it was linked to a sometimes-deadly bowel condition called intussusception.

A later study by the NIH argued that RotaShield was not responsible, but the damage had been done. Once the vaccine was deemed unsafe in the United States, it was politically impossible for Wyeth to sell it even in countries like India where it might have caused a handful of deaths while saving 100,000 lives. Plans to release it next in India were canceled.

Meanwhile, Indian children remained without a vaccine and continued to die.

The push

It’s often difficult for Americans to grasp how so many children worldwide can die from a virus that causes so few deaths in America. Malnutrition is key, experts explain, making children too weak to withstand the constant diarrhea and vomiting. Glass, who spent four years treating children with rotavirus in Bangladesh early in his career, explains it like this:

“Usually if you can rehydrate children with an IV you can save a child. But if they remain at home untreated, they can die of dehydration. They lose too much fluid and electrolytes. First they’re thirsty, then they lose consciousness, they go into shock. Their skin color changes. The body’s functions cease. They become wilted like a flower. If children lose 10 percent of body weight, they’re considered severely dehydrated. They can’t drink. They die.”

American parents awake in the middle of the night with a sick baby will call their pediatrician, who’ll send them on a drive to the local drugstore to buy an oral rehydration solution before it reaches this scenario. A poor Indian parent has no phone, pediatrician, car or local drugstore. And a parent lucky enough to obtain rehydration solution might still be out of luck: If a child is malnourished to start with, dehydration can come on so swiftly and severely that the solution won’t help. With a new sense of urgency, the India rotavirus project returned to the drawing board.

The team of scientists went in search of a new funding source and a commercial partner for the next stage of development: producing prototypes of the vaccine in India for advanced clinical trials. That’s when the Gates Foundation stepped in and the Hyderabad-based firm Bharat Biotech International joined the team.

A decade ago, Bill and Melinda Gates began directing Gates Foundation resources to address the severe time lag between development of vaccines in the West and availability in poor countries — as long as a decade or even more. In 2001, the nonprofit PATH, a recipient of Gates support, became the India project’s new funding source. In addition to providing money for the clinical trials, the agency backed the new commercial partner, Bharat Biotech.

Since 2001, PATH has provided a total of nearly $10.5 million to the project. “It was a completely new process for Bharat,” says N.K. Ganguly, MD, former head of the Indian Council of Medical Research. “When you create a prototype vaccine you need to work on stability, to develop special harvesting techniques, to use cleaner preparation methods. It’s not easy for a new company to master all these requirements.”

This is where the American scientists’ expertise was essential. “We had more knowledge of the actual virus,” Greenberg says. “I had been in the industry. I knew quality control for clinical trials.” India’s medical regulators follow World Health Organization guidelines — which the rotavirus team is aiming to meet throughout the manufacture and testing of the vaccine.

Results from the next round of clinical trials in 400 Indian infants were impressive. The vaccine was found to be safe and produced immunity in close to 90 percent of the babies after three doses.

“This was above our criteria of success,” says Georges Thiry, PhD, director of PATH’s Advancing Rotavirus Vaccine Development project. In fact, in these early studies, the vaccine candidate appeared to be more immunogenic than either of the two licensed vaccines.

The final round of clinical trials, scheduled for this summer, will involve 6,000 infants. If the results are positive and the vaccine is both safe and effective in preventing severe diarrheal disease, the vaccine could be on the market within a year or two.

Local virus does good?

The vaccine developers have achieved their goal of keeping production costs low. Manufacturing in India was the key. Packaging and dispensing of the vaccine is simpler, the cost of goods is lower. The need for profit is lower for an Indian-based manufacturing firm, Greenberg explains. And the support from international aid agencies has helped.

“The total price, if successful, will probably be under $50 million — so this vaccine could be a bargain,” Glass says. It costs $500 million to $1 billion to develop a vaccine in the West.

Now in the final phases of development, the team admits challenges remain. Next up is determining how best to deliver the vaccine to all the children who need it.

Meanwhile, more rotavirus vaccines are being tested for use in India. Merck and GlaxoSmithKline, producers of the rotavirus vaccines on the U.S. market, are working with PATH to conduct clinical trials in Africa and Asia to accelerate introduction of their vaccines into developing nations. Also being developed in India is a third vaccine, which was discovered by scientists at the NIH including Greenberg, who began his career there.

“The more the better, the sooner the better,” Thiry says. “By having more options we will increase capacity, the volume will create competition, which will hopefully reduce cost and make it more affordable.”

But the unique method of product development, producing a vaccine within the developing country where it’s needed most, will make this product particularly suited to meet the needs of Indian babies, the team’s researchers say.

“It’s been a tremendous team effort,” Bhan says. “It’s inspired so many people in India. Creating a vaccine at low cost sends a message that through innovation, you can find solutions.”