A year and a half after the ABC newsman's injury in Iraq

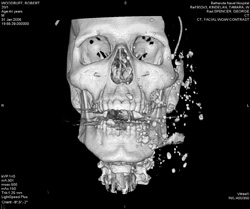

In an instant, Bob Woodruff’s head was blown apart by an IED in Iraq. In January 2006, the newly installed co-anchor of ABC’s World News Tonight was on a high-profile trip to Iraq when he and his crew, embedded with the military, encountered a roadside bomb with a remote-controlled device.

Stefan Radtke |

|

|

|

Bob and his wife, Lee, a former PR executive, will tell you that the IED devastated more than the military convoy; it shattered the Woodruff family too. Astonishingly, 17 months later, life is now returning to normal for the Woodruffs and their four children. We caught up with Lee and Bob at home in Rye, NY, shortly after they returned from a book tour for their national best seller, In an Instant. Here, with the School of Medicine’s Paul Costello, they talk about love, healing and the brain’s amazing ability to recover from traumatic injury.

When I phoned earlier today and caught you at the soccer game watching one of your children play, it all sounded pretty normal. Normal must be really welcome.

Bob Woodruff: You know, every week, every month, I’m getting back to the way that I used to be. To get back with my kids, to go watch them play sports, see them go to school, studying with them. Even as a journalist — I just came back from Cuba, returned from my first overseas reporting trip.

I was going to ask you about that.

Lee Woodruff: I have to be honest. I think there’s a part of Bob that was feeling a little naked heading out to do this.

Bob: I was very nervous when I first went down. Would I be able to deal with subjects that I hadn’t been reporting on in the last several months? Could I still do it like I could before? You know what? It came back.

Easily?

Bob: Nothing is easy. I’m always going to have some difficulties with remembering names and words. That’s just part of my traumatic brain injury. And I understand that. And that’s always a little bit of a worry. Does that mean that I’m not going to be able to do my stories the same way that I did before? Or will I just do them differently? It’s just so unsure exactly what’s going to happen.

A year ago would you have thought this was possible?

Lee: I don’t think so. A year ago at this time, I was lower than a snake’s belly, as I like to say. I hoped that he would be returning to work, but he was still really putting things together. And of course he was still missing his skull. And so we were still kind of hiding out on the old ranch here fending people off. It was a grim scene in many ways.

How has this injury changed the essence of Bob Woodruff?

Bob: I really have to spend a lot more time with my wife and my kids and my family now. I don’t feel bored when I’m around them — which happened to me sometimes before. I would need to hit the road again and start reporting on something else. Now I feel like I really need to be with them. I even told Lee (laughs), that, you know, I was a little bit of a jerk before. You know what? I’m not anymore. Whether or not that’s true, who knows. But, it’s changed me.

Can you describe what it’s like to have words lost in your brain?

Bob: It’s frustrating. I mean, my job is to be able to speak. I have to be someone who can tell a story, sometimes for an hour at a time. The good news is that my words are coming back a lot more. And there’s work in journalism that I can do without having to do live reporting. I still understand everything that I see, and I understand what’s been said. I just can’t necessarily get the words. Some day I may even get that back.

Are there words that are more difficult than others?

Bob: Yeah, I think that’s true. So many names, of friends even, I sometimes can’t remember. For example, for eight months at least I couldn’t even say Tony Blair, from England. But I could say Mahmoud Ahmadinejad, the president of Iran. Why? I don’t know.

There was no silver lining in this. Is that right?

Lee: I think the best way to say this is there are a lot of little gifts. But the people who subscribe to the theory of there’s always something good in everything, or things happen for a reason — I still have a hard time swallowing that one. I can find good things that have come out of this. But, I’d go back to January 28th in a heartbeat and trade that for anything in the world, frankly.

|

|

|

Bob, right after the IED went off you had a “white light” experience. What do you make of that?

Bob: I can only explain what I saw. And that was just me floating down below me. It only lasted about a minute. I didn’t see much beyond that. It’s probably the way it’sgoing to look when I do it again, and this time go the other direction.

So do you think that that’s the line of demarcation between life and death?

Bob: I don’t think we can really know until something happens later on. I will say that it looks pretty comfortable to me and I don’t really have much fear of death because of it.

Neither of you is from a military family. Now you’ve been thrust in a military environment. What was it like for you at the hospital, Lee?

Lee: At first it was disorienting, and then I really relaxed into it because, in the end, doctors are doctors and hospitals are hospitals and people are people. We began to feel the rhythm of the “ma’am” and the “sir” and all of that. And understand how truly lucky and grateful we were to have had this happen in the arms of the military because there was no better place for Bob to be.

Didn’t one of your friends, neurosurgeon Peter Costantino, say that Bob was in the best hands in the military?

Lee: He did. That was so comforting. Because my first thought was: What are we going to do? You know, he’s in the military hospital — and the image in my mind was government incompetence, quite frankly. And Costantino, who had been an Air Force surgeon for 15 years, called and said, “I know what you’re thinking. And I want you to know that Bob could not be in better hands than he is in the military. Because with a brain injury, it’s about numbers. And these guys are seeing these blasts every single day and they know exactly what to do and they do it without hesitating.”

Were both of you really shocked when You heard about the trouble some vets had getting care once they returned home?

Lee: Yes, I was. I think many people were shocked. That was the takeaway from Bob’s hour-long documentary as well. I think most of us assumed that the war machine had prepared the hospital system and outpatient end of things as well. Over and over again Vietnam vets have come up to us as we’ve been on the road talking about our book saying, “The system was so broken when were going through it. And we’re so disgusted to learn that nothing’s really changed.”

What have you heard from Iraq war vets and their families?

Lee: Frustration and anger. Especially among those who were brain-injured. I think that most everybody feels that great work is done in the acute care phase, certainly at the polytrauma centers. But it’s in the smaller VAs that aren’t used to dealing with head injuries and who are ill-equipped to deal with outpatient services and cognitive rehab and so forth. That’s where things really break down for these people. And the amount of paperwork that we’re making everybody do is shameful.

Bob: The VA has four post-trauma brain treatment centers, and they’re the most decent ones within the VA. But the sad thing is that so many of these military guys want to be close to their homes and their families. So to have just four of them around the country doesn’t really quite answer the need. Meanwhile, there often are good hospitals right around where they live, but since they’re not part of the VA, their benefits don’t necessarily give them the right to go to them. And that’s got to change.

What would you say to medical students if you were to meet with a class today or tomorrow?

Lee: Our favorite doctors were ones who could couch things in human terms, who could look us in the eye, who could understand our pain, who could say to us, “You know what, this does suck [laughs]. We get it. And we wish we could make it better. And I’m gonna tell you the worst-case scenarios but I’m gonna tell you to just keep hoping in there too.” Doctors don’t talk about hope. And they don’t talk about faith. And I understand that. Not everybody has faith. But in a hospital, people are clutching for something. And there’s a feeling in the room when the doctor comes in of collectively sucking in your breath and thinking: OK, what now?

There was a physician in the hospital who we called Dr. Downer. And it seemed like every time she came in with even the most positive things to say, she had to put the caveat on there right out in front — God forbid we had a little too much hope. And I still to this day feel traumatized. There are moments I’m sitting there waiting for Bob just to blow up with some kind of seizure because of all the collateral damage that she did to me by being so completely careful to tell me everything that could happen.

There should be a course in just forcing people to confront the human side of what it means to deliver bad news. Or to give somebody a prognosis but do it in a way that saves everybody’s dignity.

When a loved one has a brain injury you have to wonder: will they love me, will they be the same. Did you confront this?

Lee: I really did. For me, what it came down to was I wanted Bob’s sense of humor to be intact. I wanted his ability to display love for his family to be there. I wanted his intelligence to be intact. And I thought if I could have those things, the other stuff really didn’t matter.

So is love the great healer?

Bob: Our love for each other is just much more than it was before. And it was gigantic even before.

What next?

Lee: I think we’re all moving forward, we’re putting one step forward and one step further away from that day each day. The foundation’s incredibly exciting. It’s the Bob Woodruff Family Fund for Traumatic Brain Injury (bobwoodrufffamilyfund.org). Initially the focus is on traumatic brain injury and administering money to individuals and organizations that are in the rehab world and providing that extra link that a lot of these guys don’t have access to once they’re discharged. But our big goal is to do a help-a-hero program where we’re reaching out to all wounded vets and their families.Comments? Contact Stanford Medicine at