Upfront

Garbage strike

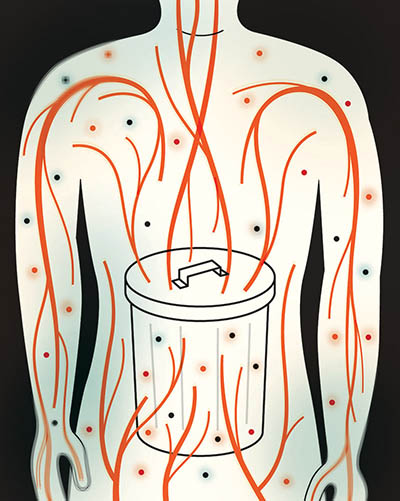

Normally, the body is extremely efficient at taking out the garbage. Two hundred billion cells die every day in our bodies, and most get cleared out within a matter of seconds. But when this process breaks down and garbage, in the form of dead cells, starts building up in the walls of blood vessels, it’s not a good thing.

Researchers led by Nicholas Leeper, MD, assistant professor of cardiovascular medicine and of vascular surgery, now have evidence that faulty garbage disposal explains why variation in one particular stretch of chromosome 9 increases risk for a wide range of cardiovascular diseases, including stroke, heart attacks and aneurysms.

Their research, published in the Journal of Clinical Investigation, shows that disturbing the usual genetic sequence at chromosome location 9p21 leads old cells and debris to build up in the walls of blood vessels.

In studies with mice with atherosclerosis, the researchers showed that this genetic variation leads to impaired “efferocytosis” — from the Latin for “take to the grave” — the process by which dead or necrotic cells are removed. Mice with this genetic variation showed an increase in buildup of these dead cells, further advancing their atherosclerosis.

“If you were born with genetic variation at the 9p21 locus, your risk of heart disease is elevated, though we haven’t understood why,” Leeper says. “This research gets at that hidden risk. You can be a nonsmoker, be thin, have low blood pressure and still be at risk for a heart attack if you were born with this variant. This work may help explain that inherited risk factor, and more importantly help develop a new therapy to prevent the heritable component of cardiovascular disease.”