Sculpting bones

A technique that requires precision, artistry and, from the patient, true grit

In a little red Hello Kitty bag, 7-year-old Giana Brown kept her surgical adjustment tools: two small wrenches, six colored pencils and a printed adjustment prescription sheet. Two or three times each day for more than six months, she sat down, took out her tools and checked which settings she needed to change on the brace affixed to her lower left leg.

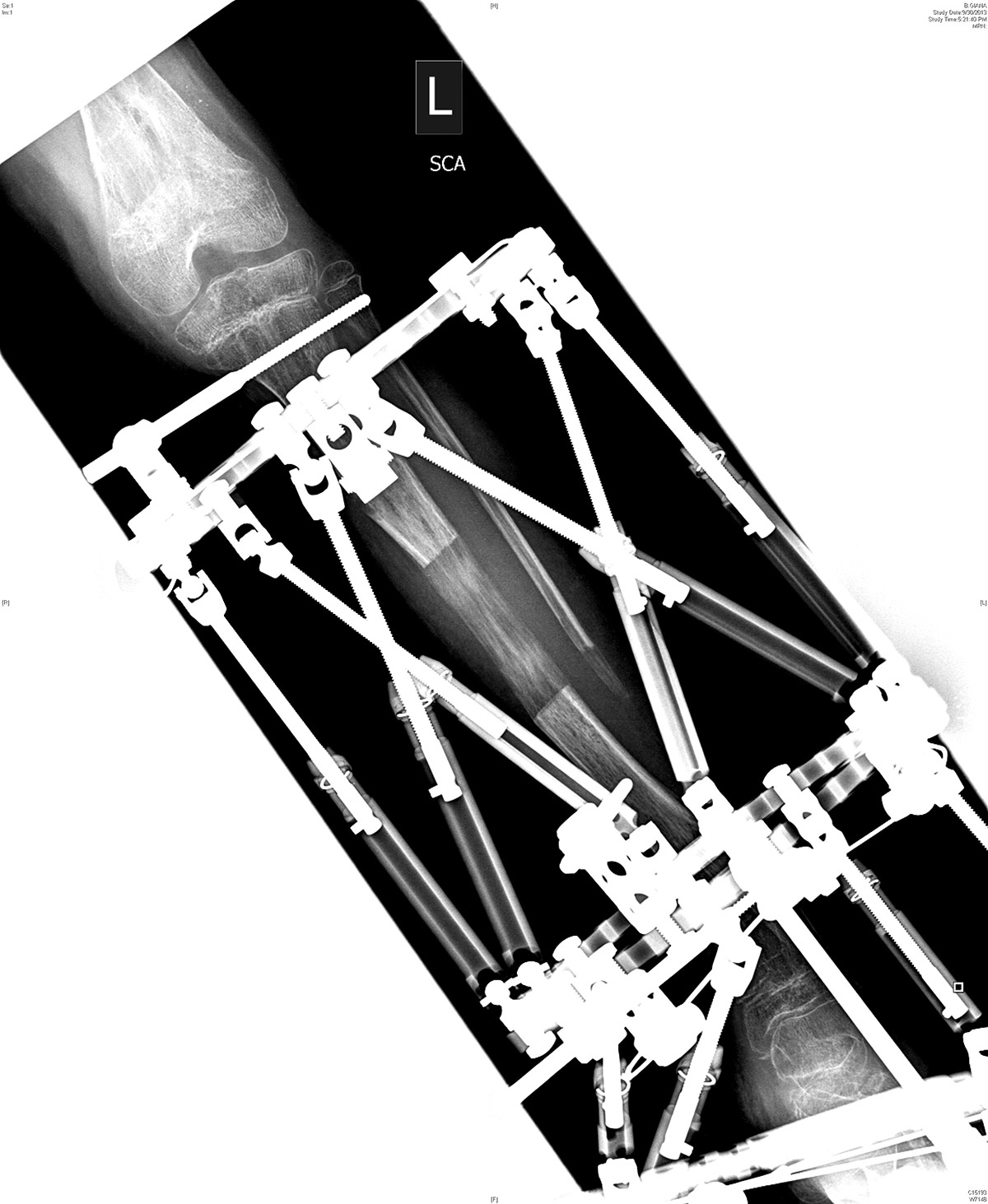

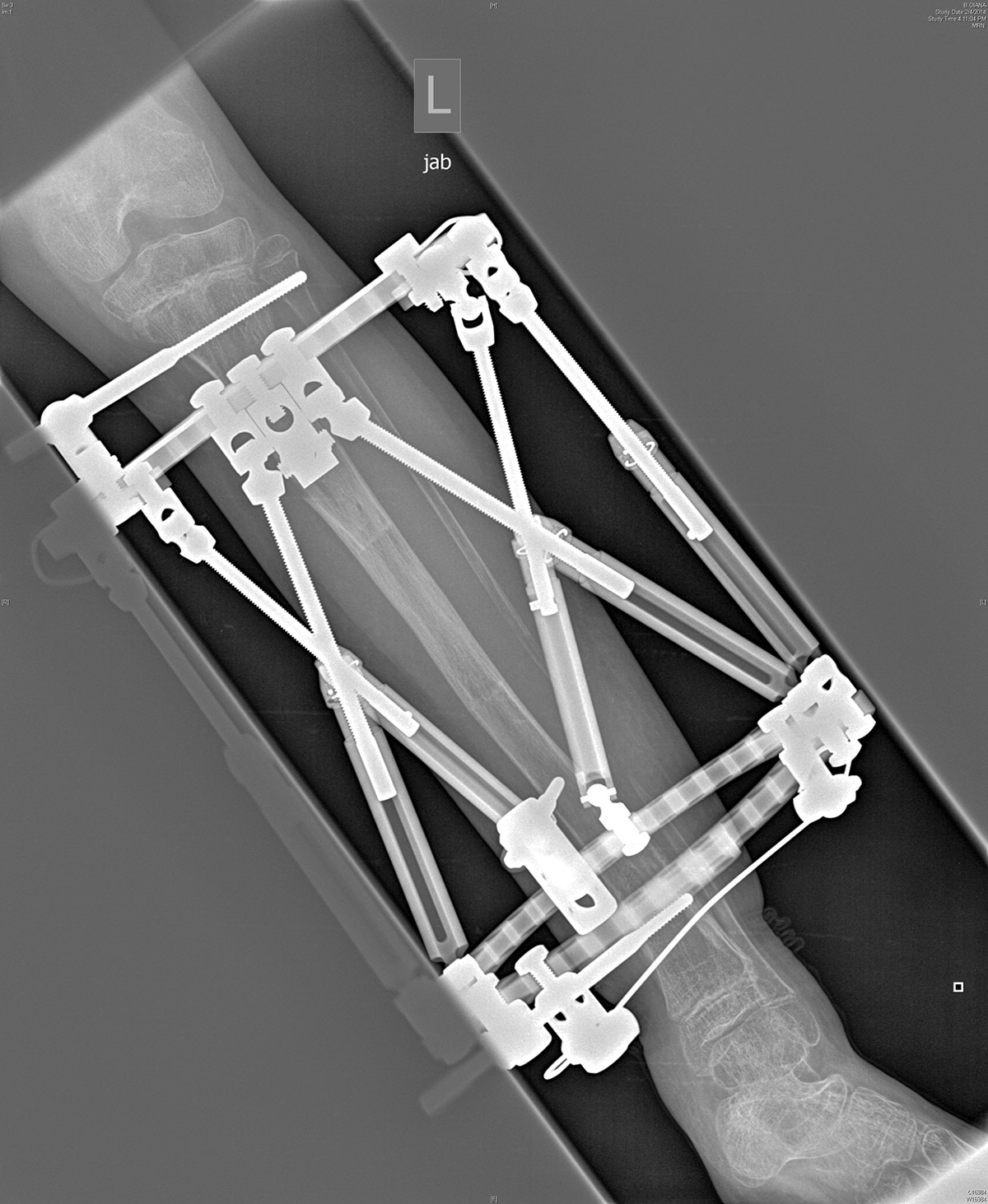

The brace, known as an external fixator, formed a cage around her limb, with six color-coded, extendable metal bars, called struts, connecting two flat, metal rings — one encircling her leg just below her knee, the other near her ankle. The rings were fastened to her leg by long, thin pins that went into her tibia, the larger of the two long bones in the lower leg. Giana, with temporary flower tattoos encircling her wrists, used one of her wrenches to turn adjustment knobs on the struts to the prescribed numeric setting, checking each one off with a matching colored pencil.

When Giana turned the knob, it lengthened the fixator, thereby widening a surgically created gap in her bone. In that gap, bone-producing cells called osteoblasts were collecting across a bridge of collagen that the bone itself had created in the first days after surgery. Stretching this gap gradually, exactly 1 millimeter a day, fostered the process of cellular generation, called “distraction osteogenesis,” which ultimately increased the length of her tibia bone by nearly 3 inches.

Though it’s not a stretch to say an external fixator resembles a medieval torture device, orthopaedists and patients alike see it as a modern technological wonder. The apparatus on Giana’s leg, called a Taylor Spatial Frame, makes possible highly precise, computer-guided bone lengthening and repair. But it’s not for the faint of heart.

“Sometimes it would take us 15 minutes to get to the number we needed,” says her dad, Greg Brown. Giana was particularly sensitive to even the slightest pain, but like all patients using the brace it was up to her or her caregivers to make the daily adjustments. “She’d move it a little, feel it and stop for a moment. But she was in control.”

For best viewing with faster connections, watch in full-screen mode, with resolution setting (lower right) at 720p.

Produced by Lighthaus Inc.

Suki and Greg Brown first noticed an increasing unevenness in their daughter’s legs when she was about two and a half. “The first sign was when she was running,” says Greg. “Her left foot looked like it was pointing out way off to the left, more than 45 degrees, and her left leg wasn’t as long as the other.”

Her parents began by putting inserts in her shoes, and eventually had lifts — platforms that would equalize her leg length — added to the soles of her shoes. “We realized that her hips weren’t lining up,” says Greg. “It was getting worse.”

Shortly after Giana’s fifth birthday, her primary care doctor referred her to Lawrence Rinsky, MD, chief of pediatric orthopaedic surgery at Lucile Packard Children’s Hospital Stanford and professor of orthopaedic surgery at Stanford’s School of Medicine. The X-rays Rinsky ordered for Giana showed benign tumors inside her bones, mostly at the ends of her long bones — the femur (in the thigh) and tibia (in the shin). He also found some in the middle of her femur. Rinsky diagnosed her with “non-ossifying fibromas,” a disorder that would make her bones vulnerable to fracture.

Just a few months later, in October 2011, it became clear that Giana’s bone disorder was more rare and complex than anyone had suspected. At her school’s after-care program, she slipped on a book and fell, and in the next moment she was curled in a ball on the floor. “She wasn’t screaming or crying. She just wouldn’t budge,” says Greg. “It was frightening because I couldn’t help her. So we called an ambulance.”

1. When first getting the frame: "It's kind of hard at first, but you'll get used to it. It's a little scary, but you'll be fine if you're brave."

2. "Take your clothes and get snaps put in them."

3. When sleeping: "Put a pillow under your foot so it doesn't just hang there."

4. When taking your first step: "Start with the foot without the brace and take your brace foot and try a little weight at first."

5. "Turning the struts was painful and scary. Turning them myself made it easier because I could stop when it hurt and start again after I took a break."

6. Dealing with pain: "If you're having a hard time dealing with your pain, just take a few deep breaths and it will feel better."

At the hospital, Rinsky was out of town, so orthopaedic surgeon Jeffrey Young, MD, took the case. X-rays revealed a spiral fracture that twisted smoothly down Giana’s femur, splitting it clear through. “We couldn’t believe it,” says Greg, who quickly learned a lot about bones. “That’s the strongest bone in the body, and it broke so easily.” The fragility of Giana’s bone, and skin pigment marks known as “café au lait” spots, led Stanford pathologist Jesse McKenney, MD, to make the rare diagnosis of Jaffe-Campanacci syndrome.

Jaffe-Campanacci can include a range of symptoms, from non-ossifying fibromas and café au lait spots — both of which Giana had — to intellectual impairment, eye and heart malformations, failure of one or both testicles to descend in boys, and, in both sexes, diminished or absent sex hormone production that can result in infertility. “Fortunately,” says Greg, “Giana didn’t seem to have these other aspects of the syndrome.”

Giana needed two repairs: to have her broken left femur set and her left tibia lengthened and straightened. Although this would not make her bones less fragile or prone to breaking, it would make her more stable on her feet in a way that shoe platforms could not. Her surgeon knew that these corrections would each take several months to heal, but would require different approaches: for the femur, an internal fixator that would be bolted directly alongside the bone; for the tibia, the Taylor Spatial Frame, which could lengthen and straighten at the same time. He explained the process. Then it was up to the family to decide whether to do both repairs at the same time. “I told them I would be there for them every step of the way,” says Young, a clinical assistant professor of orthopaedic surgery at Stanford.

“We could have started the lengthening right then,” says Suki. “But mentally we didn’t have our heads around this yet.”

Giana’s parents decided to let her femur heal first — which would take about a year — and then begin the lengthening and straightening process the following summer.

“Between two and seven people per 10,000 in the United States are affected by longitudinal deficiencies,” says Young, referring to conditions of unequal limb length. But the Taylor Spatial Frame is used for a variety of conditions, he explains, including deformities that happen after a bone break or injury, such as when bone growth stops, when there is bone loss, or when a broken bone heals incorrectly (also called “malunion”). Orthopaedic surgeons also use the frame to heal limb deformities caused by infection, which can cause bones to stop growing or grow at the wrong angle, or cause areas of bone loss. Some surgeons use the frame to extend limbs for people with achondroplasia, also known as dwarfism. In California, Young says, only a handful of surgeons are trained to use the spatial frame, and even fewer use it on children.

“Approximately 1 percent of surgeons nationally are qualified to use the Taylor Spatial Frame, with the community growing slowly given what it enables the surgeon to address,” says Mark Waugh, vice president, extremities and limb restoration for Smith & Nephew, the company that distributes the device. “It’s not a surgery you do and step away from,” he adds. “Surgeons tend to build a relationship with the patient and their family given the interactive nature of the healing process.”

On July 12, 2013, Giana went into surgery. Young had already planned where to affix the frame, and where to cut her tibia to minimize complications from her bone disease. Once Giana was asleep and anesthetized, Young cleaned her leg and placed a 1.8-millimeter stainless steel wire — called the reference wire — through her leg and bone. This wire served as a guide for the most important part of the frame: the reference ring. Acting as the point of origin for all the measurements that would go into the prescription, the reference ring also served as the top of the frame. Young further secured the ring with three metal pins that poked through skin and flesh to reach the bone.

With the top ring affixed, Young set about cutting the tibia, making two 1- to 1.5-centimeter incisions about an inch apart, halfway between the top and bottom of the frame. He then passed a wire, called a Gigli saw, through one incision, into Giana’s leg, circling most of the bone, and back out the other incision. “Using that wire like a cheese slicer,” Young explains, “I cut the bone, sawing back and forth. We avoid using a motorized saw because the heat can burn and kill the bone cells, effectively cauterizing the areas we need to heal.” Around every bone is a thin membrane called the periosteum — meaning, literally, “around the bone” — which Young was careful to keep in place. “It creates a safe boundary and is important for the bone healing as well.”

Young completed half the cut, affixed the rest of the frame, then finished cutting with the bone fully stabilized by the frame. He also placed a second frame on Giana’s foot to support her ankle. The resulting apparatus looked like the steel frame of a giant, open-air boot.

Although Giana didn’t have the full spectrum of symptoms often seen with Jaffe-Campanacci syndrome, she was extremely sensitive to pain. She spent a few nights recovering at the hospital, but at home the pain was unbearable. “She didn’t leave her bed for five days,” says Greg. “We were supposed to be able to move her, but she was in so much pain that we couldn’t.” She’d reached her limit on pain medications, and they didn’t seem to be working. Suki and Greg were deeply concerned, so they called Young, who did what few surgeons are known to do: He went to Giana’s house to assess her, and helped the family decide to bring her back to the hospital.

“I’ll always thank him for that,” says Suki. “He knew what was good for that child.”

That night, Young connected the two braces — the one on Giana’s foot and the one on her tibia bone — which he had originally left separated to allow her ankle to move. Connecting them relieved the pressure on Giana’s ankle. “Once that was fixed, it seemed to help,” says Greg.

Greg, Suki and Giana all learned how to turn the struts to the prescription settings for each day. “After the first two weeks, Giana didn’t let anybody else turn the struts. She had to turn them herself,” says Suki. “She had two little wrenches, like they were made for kids’ hands. Every day at a certain time, she would turn them, then mark the paper with a little colored pencil. She never complained, just got on and did it.”

The greater challenge was cleaning the pin sites, which needed to be done at least every other day. “It was extremely painful,” says Suki, “far worse than adjusting the struts.” The frame’s size was also somewhat cumbersome, causing some bumps and bruises on her healthy leg, sometimes on other people’s legs, and often bringing unwelcome stares from other children.

“It was draconian-looking,” says Greg, “and horrible to imagine what it was doing to her leg. But it was also magnificent, extending her leg and bringing her foot forward in one operation.”

For Young, the frame stands alone as an ideal tool for healing his pediatric patients. “I really like how the technology allows me to basically sculpt the bone,” he says. “It’s the perfect blend of engineering and art.”

The technique was discovered by chance more than 60 years ago, by a doctor working alone in a remote province of Siberia, Russia.

In Limb Lengthening and Reconstruction Surgery — a textbook for orthopaedic surgeons practicing this approach — Svetlana Ilizarov, MD, tells the story of her father’s discovery. Gavriil Ilizarov, MD, PhD, started out as a general practitioner, but learned orthopaedic surgery by necessity as the only doctor in an area “the size of a small European country.” For his patients, many of whom were Russian soldiers returning from World War II with a variety of bone injuries, he developed a new type of external fixator device. Unlike previous models, his completely encircled the limb, with parallel bars screwed to rings above and below the break. By tightening the bars on the fixator, bones with missing fragments or gaps could be healed using grafted bone and compression to encourage the pieces of bone to fuse back together. Just as Giana would decades later, and as the majority of patients using an external fixator still do, Ilizarov’s patients were also responsible for adjusting the screws on the fixator — only their job was to tighten, not lengthen, the screws to increase compression until the bone healed.

On one occasion in the early 1950s, a patient turned the screws in the wrong direction, separating the bone pieces instead of closing them, writes Svetlana Ilizarov. Her father was shocked to find that new bone had grown in the gap. This accidental discovery led to his method of distraction osteogenesis, through which non-healing fractures could be corrected, deformed limbs straightened and uneven limbs lengthened. Only muscles and tendons — which can stretch only so far — set the limits.

“The Ilizarov method … revolutionized the process of deformity correction,” writes Svetlana.

Ilizarov’s method did not reach the United States until the late 1980s. When it did, two early adopters, Charles Taylor, MD, an orthopaedic surgeon in Memphis, Tenn., and his brother, Harold Taylor, an engineer, redesigned it. In the early 1990s, they replaced the long, parallel bars that screwed into the frame with hinged struts that could change length like a telescope, one end fitting inside the other. They set the struts at angles to each other, making three triangular formations that encircled the limb in a zigzag. Each strut could be adjusted individually, allowing complete flexibility of the rings in relation to each other, with no equipment changes required during healing.

The new design also greatly increased the complexity of the device’s settings. So, with the new Taylor Spatial Frame came a computer program that used the exact settings planned before surgery to generate a prescription for correction in the weeks or months following surgery. “The computer program is mathematically accurate to within a millionth of an inch and a ten-thousandth of a degree,” writes Charles Taylor in Limb Lengthening and Reconstruction.

Stanford’s Young, who was first introduced to the device during his residency at Northwestern Memorial Hospital, has also used the frame to treat patients during orthopaedic medical missions in Nicaragua and Haiti. “The computerized prescription sits on the spatial frame website, so it provides the ability to share cases and adjust prescriptions remotely,” he says.

In October 2013, Young removed the frame on Giana’s foot. Physical therapy helped her get her ankle back in motion again. Then, on Valentine’s Day 2014, with her left leg lengthened by close to 3 inches and rotated so that her foot was aligned, Giana’s spatial frame was removed and a cast was put on for one month. From the cast, she graduated to a boot, which she could remove at night — a welcome relief.

Giana will need to be assessed again when she’s in her early teens, and her left leg may need further lengthening if it continues to grow at a slower pace than her right. Because the fragility caused by her rare bone disease will continue, she’ll need to steer clear of the highest impact activities like gymnastics or soccer, but still has a lot to look forward to.

“I want to do cannonballs into the water,” Giana says. “I want to climb up onto the play structure and swing from the monkey bars and run and play tag. I want to go to the beach — that’s what I want to do most of all.” And now that her leg is healed enough that there’s no risk of sand getting into the wounds left by the pins, that’s exactly what she’s ready to do.