In the groove

Behind the scenes in the OR

Dawn was breaking outside Stanford Hospital, but in the OR the team in suite No. 4 was wrapping up a 12-hour aneurysm clipping. Everyone was spent but still focused. They began to fall into a rhythm, which visibly recharged the entire team.

Extras

More on checklists in medical care at the The New Yorker

Within 30 seconds, they were all operating from the same groove: Heads began to bob, toes tapped, the scrub tech strummed his air guitar with a pair of forceps, and off to the side the circulating nurse did a little Michael Jackson spin-a-roo as she notched up the music.

The OR can be a gnarly place. Same for the emergency room and the catheterization lab. But in the OR, gnarly can go on for hours and hours and hours. Knowing how and when to tame the tension is invaluable, and surgeons consider it an art form.

“It’s a fine balance,” says Gary Steinberg, MD, PhD, professor and chair of neurosurgery at Stanford. “You relax people enough so that they can perform their best, but not so much that they start missing details.” He says that Stanford’s OR is consciously working toward a more relaxed attitude, and that music plays a big role. He shakes his head: “We never used to play music in the operating room when I was training.”

It was during the ’80s that Steinberg went through his training at Stanford. In those days, the hierarchical mode of teaching was as much a rite of passage as it was an education. Ridicule, hazing and tirades were par for the course. These days, the training leans more toward team dynamics, building an esprit de corps. This is partially because the newer generation of surgeons seeks a more realistic work-life balance. “In the old days, you killed yourself to be a doctor or a surgeon,” says assistant professor of vascular surgery Venita Chandra, MD. “Everything else was put on hold. Today, that’s no longer acceptable.”

Let’s backtrack 12 hours to the start of the procedure in suite No. 4. Neurosurgery chief resident Anand Veeravagu, MD, mulls over the music menu that will accompany this long-haul procedure. To get the team teed up, he puts on Pink’s Let’s Get This Party Started and it sparks the desired effect. The anesthesiologist’s focus is on the patient, but you can see he’s feeling the beat. Neurodiagnostic technologist Jackie Varga two-steps around him, attaching electrodes to the patient’s legs. A nurse rhythmically swabs the patient’s head with antiseptic, and the circulating nurse glides in and around them all. This group works together so frequently that the bustle around the table looks choreographed. And even though they’re all grooving to the tunes, the care and safety of the patient is deeply ingrained and permanently paramount. Abruptly, Veeravagu turns off the music and the sudden silence grabs everyone’s attention. He calls for the timeout and review of the surgical checklist, procedures that happen before every surgery at Stanford.

Photo courtesy of Jackie Varga.

Step by step, they verify that everything necessary for the patient and the surgery is at hand. Everyone, regardless of seniority or position, is encouraged to ask questions or voice concerns. Then, a quick round of introductions — including the surgical team and observers alike — concludes the timeout. The timeout and checklist were instituted about seven years ago with the goal of improving patient safety. But one can see how they also knit the group together, bolstering team dynamics.

With his scalpel, Veeravagu makes the first incision, then fires up the bovie, an instrument that cauterizes as it cuts. It makes a staticky hum, and a thread of smoke spirals up from the patient, producing the vaguely off-putting smell of burning flesh. The visitors around the periphery watch with arms folded, trying to ignore the chilly air, but the team around the table is oblivious to the temperature. They’re focused on the procedure as they stand under bright lights, swaddled in blue surgical gowns and gloves atop the standard-issue blue scrubs worn by everyone (other than the patient) who enters Stanford’s OR.

Not all OR attire is blue, though. Clogs have been the OR’s go-to shoe for decades, and Chandra is sporting a new hot-pink pair. She says she got them “just to have a little fun.” Not too good for rock climbing, but their generous arch support makes them great for long bouts of standing and toe-tapping to the tunes.

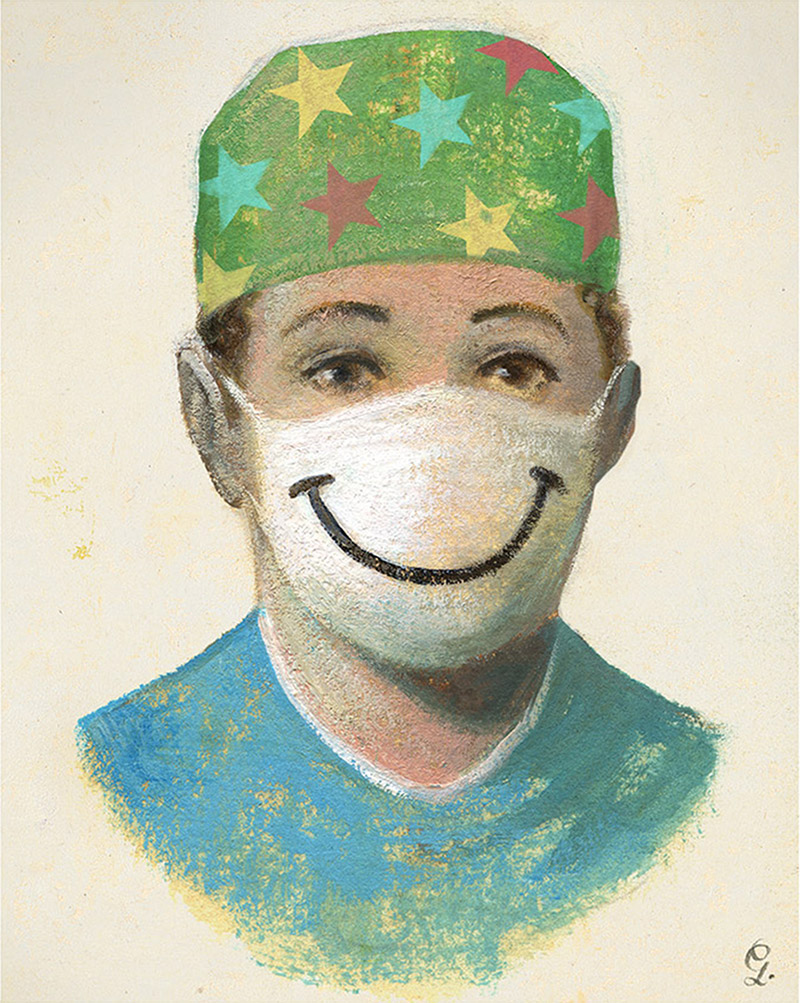

As for the hats everyone in the OR must wear to cover their hair, colorful toppers can be a tip-off to the personality of the soul below. Varga, the neurodiagnostic tech and a kind soul, is a serial hatter. The ubiquitous shower-cap style is good for covering long hair, but bad for flattering the face. Varga decided to make her own hats and soon co-workers began to request them. Now she makes them as gifts. “I go crazy with all the fabric choices. When I see a fabric, and it reminds me of a person, I think: Well, they just have to have a hat.” She guesses she’s made at least 200 over the years.

Photo courtesy of Jackie Varga.

In suite No. 4, it’s the seventh hour, and the action has ebbed. Now, the surgeons can finally step out to give their kidneys a break. The music picks up, as does the conversation. There’s playful banter, and wisecracks zing between Veeravagu and scrub tech Chip Hamilton. Hamilton has worked closely with the surgeons for nine years, anticipating their next moves, being at the ready with the proper instrument, device or dressing. He says the OR is much less intense than it once was. “There’s no longer room for aggression or embarrassment.” He smiles and adds, “it’s more like family now.”

He calls to a nurse who’s fiddling with the music, “Cue up Sister Sledge!” and he goes back to ribbing Veeravagu. In the background: We are family. Get up everybody and sing....