SPRING 2014 CONTENTS

Home

Fresh starts for hearts

Cardiovascular medicine looks to stem cells for answers

Hiding in plain sight

A high-cholesterol gene

A change of heart

A conversation with Dick Cheney

Switching course

Untangling a birth defect decades later

Dear Dr. Shumway

A boy, two frogs and an airmail letter

Easy does it

Aortic valve replacement without open-heart surgery gains ground

DOWNLOAD PRINTABLE

ISSUE (PDF)

Special Report

Dear Dr. Shumway

A boy, two frogs and an airmail letter

By M.A. Malone

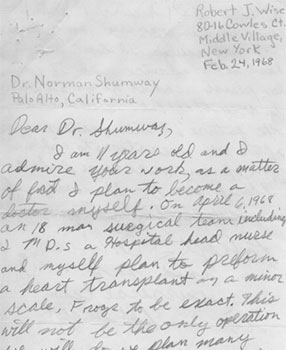

The envelope was addressed in pencil, postmarked March 25, 1968, with 2 cents postage due, and was simply addressed: “Dr. Norman Shumway, Stanford, California.” For 45 years, it lay in the archives of Stanford medical center’s communications office, one document among thousands that intern Jerome Macalma was charged with scanning in the summer of 2013.

The enclosed letter got right to the point: “Dear Dr. Shumway, I am 11 years old and I admire your work.” Two months earlier, Shumway and his team had performed the first successful human heart transplant in the United States, and the pioneering surgeons were celebrated worldwide.

The 11-year-old went on to say that he “and his 18-man surgical team” were planning to perform a transplant six weeks hence, and he would be most grateful if Dr. Shumway would impart a bit of advice. The letter was signed, “Robert J. A. Wise, 1st Surgeon.” Below his John Hancock-sized signature were the signatures of the “2nd, 3rd and 4th” surgeons on his team.

These many years later, those of us in the office who read the letter were instantly charmed. Here was a kid who’d clearly been served a couple extra helpings of chutzpah, and we were dying to discover where his audacity had taken him. We had to track him down.

So Macalma turned to Facebook: Using the names of the four “surgeons,” he zeroed in on the correct Robert Wise. We were ecstatic. We emailed him the letter, and asked if he’d be willing to talk with us. He was. In fact, he said he “was flabbergasted to discover that anyone actually had a record of the letter.”

We called the following afternoon. “Of course, I remember writing the letter!” he laughed. “I haven’t opened the attachment yet, but I’ll do it right now.” Enthralled, we listened as he worked his way through the letter, and the 56-year-old fondly re-connected with his 11-year-old self. His memories poured out, and our mystery began to dissolve away.

His interest in medicine went back to age 4 when his grandparents lived with his family. Their poor health required frequent visits from the family physician. He was a gentle, patient man and Wise was his shadow, “rounding” with him as he did his exams.

For this youngster from Middle Village, N.Y., medicine was mother’s milk. While most kids opened a newspaper to find the funnies and check the box scores, Wise scoured the papers for medically related articles. Instead of a tree house or fort, he built a lab in a corner of his basement where he did his chemistry experiments, surrounded by animal specimens in jars, and Frank Netter anatomical drawings on the walls. He devoured medical books and journals, but had little taste for schoolbooks and homework. His obsession with medicine was legendary. “I was something of a kooky celebrity at school,” he remembered with pride.

At age 16, he began volunteering in the emergency department at LaGuardia Hospital in Queens, N.Y. He developed X-rays, set up suture trays, took vitals and tagged along with the doctors. “That was my wheelhouse,” he said. “That’s exactly where I wanted to be.” He practically lived there during the summer, working 16 to 18 hours at a stretch. By age 18, he was certified as an emergency medical technician. He worked his way through college and medical school, and eventually became a — what else — physician in emergency medicine, with a clinical interest in cardiovascular emergencies.

So, now we knew that this letter to Shumway wasn’t just an 11-year-old’s slice of pie in the sky — Wise really had become a bona fide doctor. But we still wanted to hear about that transplant, and we wondered if Shumway had ever written back. Unfortunately, he hadn’t. But Wise had also sent letters to Christiaan Barnard, MD, and Adrian Kantrowitz, MD, two other transplant pioneers. Within a week, he received a long, encouraging letter from Kantrowitz. “I remember standing in the living room in complete disbelief that someone had actually responded!”

So now we knew that this letter to Shumway wasn’t just an 11-year-old’s slice of pie in the sky — Wise really had become a bona fide doctor.

As for that scheduled transplant, word travelled fast in the ’hood, and it was quickly SRO in the operating theater, a.k.a., the Wises’ garage. The two patients were prepped and positioned on the table. The scalpels, hemostats and sutures were at the ready. They’d been donated by “2nd Surgeon” T. Bower, MD, the father of one of Wise’s friends, and an ardent supporter of his medical zeal. He also donated a bottle of ethyl chloride, which they used in combination with hypothermia to anesthetize the patients. “We filled a Planters Peanuts can with the ethyl chloride,” Wise explained, then put the patients — two backyard bullfrogs — “into the can and shut the lid to induce anesthesia, after which the frogs were kept on ice-filled trays.”

Plastic insulation from fine-gauge copper wiring was used to connect the frogs’ circulatory systems. They split the insulation, removed the wire, then sterilized it in alcohol. “We laid the vessels next to each other, then slipped them into the insulators and tied them off with sutures.” Using blue and red, they color-coded them to the arterial and venous connections. Gloved and gowned, the team of five worked its way through the procedure. “It wasn’t so much a heart transplant,” Wise recalled. “It was more like a heart-swap.”

Without a doubt, this is a story with a happy ending. The airmail letter launched a mystery that turned into a terrific tale; the boy really did grow up to be a doctor. And the two frogs? They made their mark in the annals of neighborhood history, but, alas, they croaked on the table. SM

M.A. Malone is the director of broadcast and new media in the School of Medicine’s Office of Communication & Public Affairs. Contact M.A. Malone