FALL 2013 CONTENTS

Home

Hello in there

Seeing the fetus as a patient

Gone too soon

What's behind the high U.S. infant mortality rate

The children's defender

A conversation with Marian Wright Edelman

Too deeply attached

The rise of placenta accreta

Labor day

The c-section comes under review

Changing expectations

New hope for high-risk births

Inside information

What parents may – or may not – want to know about their developing fetus

DOWNLOAD PRINTABLE

ISSUE (PDF)

Plus

Almost without hope

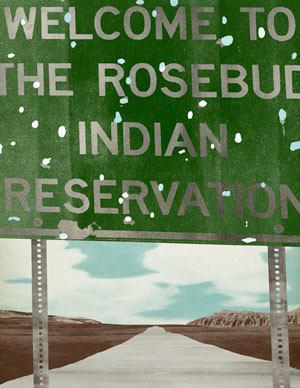

Seeking a path to health on the Rosebud Indian Reservation

By Tracie White

Illustrations by Jeffrey Decoster

In the emergency room of the Rosebud Indian Health Service Hospital, suicide attempts by drug overdose are seen nearly nightly. Alcohol-related car accident injuries fill many of the small hospital’s beds, competing for space with tuberculosis, pneumonia and liver and kidney failure. Diabetes is common, leading to loss of life and limb.

The physical complications of poverty, joblessness and epidemic rates of alcoholism, diabetes and depression spill over into the wards here at the only hospital on the Rosebud Reservation, which has a population of 13,000 and stretches across 1,970 square miles of South Dakota prairie. Life is short, violence high and health care lacking in Todd County, the second poorest county in the nation.

“There are three ‘spiritual’ paths here: Native Lakota, Christian or alcoholism,” says Rick Emery, a physician assistant here for the past 13 years. He’s hunkered down in command central, a small office in the ER, awaiting the arrival of an assault victim. It’s late March — spring break for the local schools. Drug- and alcohol-related cases are up. The staff morale, down.

“Bath salts, meth, Sudafed, anything that’s cheap,” Emery says. His hair is gray, his kind face weathered. “It’s worse when school’s out, when kids on the reservation have nothing to do. We get young people, 17, 18 years old, coming in with chest pains.” Sometimes they’re drug-induced, sometimes not. The night before, a 16-year-old came in with a severe anxiety attack. The night before that, a 25-year-old male who had hanged himself arrived too late to save.

Cursed with some of the highest suicide rates in the country, tribal leaders declared a state of emergency here back in 2007 making headlines in The New York Times. But today, six years later, not much has changed. Across the United States, American Indian and Alaska Native youth ages 15 to 24 are still committing suicide at rates three times the national average of 13 per 100,000 people for their age group, according to the U.S. surgeon general. On the Great Plains, the suicide rate for Native Americans is 10 times the national average. Unemployment hovers at 80 percent, and the life expectancy for males is in the upper 40s, about 30 years lower than the U.S. average.

The ambulance arrives with the assault victim — a middle-aged Native American male with a blood alcohol content of 0.2 and a wide gash across his skull. Someone attempted to choke him, then bashed him in the head with a piece of firewood. The patient before him was a 26-year-old woman and former meth addict suffering severe vaginal bleeding. The patient after him: a 2-year-old boy with a raging dental infection who will have to be helicoptered out to a hospital hundreds of miles away to get the care he needs.

“These were all Sioux land from the Missouri River in South Dakota west through eastern Wyoming into southern Montana,” says Emery, referring to the wide swath of land that stretches across the northern Great Plains. Emery is a member of the Lakota Sioux. He worked as an Army medic for 17 years before returning home to his reservation and this hospital. The military has provided a way out of poverty for many here. “Lakota were nomadic tribes who followed the buffalo. Then the government put us in these desolate places. ‘We’ll take all this land in exchange for health care forever,’ they told my people. They just didn’t say what standard of health care that would be.”

I can only wonder: How did things get so bad out here in the middle of the windswept prairies, land of majestic sunsets and home to once-proud warriors? Is there any hope for the future?

I’ve found my way into this emergency room as a writer covering Stanford students in a class on rural health care and Native American health disparities. The course ends with a weeklong trip to the Rosebud Reservation, where students volunteer in the hospital and help build low-income housing for Habitat for Humanity [see sidebar on the right].

Few communities in the United States, perhaps some in the outer reaches of Montana or Alaska, are so isolated. To get here, I fly from San Francisco into Sioux Falls, one of the two major cities in South Dakota, then rent a car and drive west across hundreds of miles of empty ranchland, Laura Ingalls Wilder territory. Traveling Highway 90, I cross the Missouri River, then turn left at the town of Murdo, population 468, and head into Indian Country. The Rosebud Reservation is at the end of a highway, down a road, around a bend that leads to nowhere.

Three hours of driving brings me to my destination, the town of Mission. The Indian Health Service hospital is situated midway between the two largest towns on the reservation, Mission and Rosebud, both with populations of about 1,500. The students are staying in the Habitat for Humanity dorms, and I plan to meet with Shane Red Hawk before connecting with them. Red Hawk is a community leader who, along with his wife, Noella, helps at-risk teens at the Buffalo Jump Cafe and Teen Center near the center of town. It won’t be hard to find, I’ve been assured. It’s on the street corner next to the only stoplight in town.

Downtown Mission is about half a mile long with few landmarks. There’s a Wells Fargo, a Subway sandwich shop, a few express loan businesses, an Episcopal church and a post office. The buildings look both temporary and unfriendly — lots of aluminum siding, few windows — like a community was forced to move here that didn’t plan on staying long. There are no malls, no movie theaters, no bowling alleys. Leading into town, there’s a large, tribal-owned grocery store empty of both food and customers — no one seems to be able to tell me exactly why. The parking lot, on the other hand, is busy. Cars line up at the drive-through alcohol kiosk, and teenagers and families hang out, chatting. One young man, his boot resting on the bumper of a pickup, wears a T-shirt that catches my attention: “Not just another Third World country.” I drive on, turn right at the stoplight and park in front of Buffalo Jump.

The sounds of video games ping from the corner of the dark, cozy cafe. Two teens laugh together. Red Hawk, tall and imposing, with a long, brown ponytail, sits alone at a corner table. He nods me over and waits for questions. Red Hawk grew up on the reservation, then left to join the Navy at 17. He returned home in 2006 after hearing about how young people were killing themselves here. He came back with Noella, opening the center as a safe place for kids to hang out and to introduce them to the forgotten ways of Native spirituality.

“I’ve had kids brought to me after being cut down from trying to hang themselves,” he says. “It’s humbling when a teenager arrives with swollen lips and fingers still blue.”

He continues: “My heart’s always been here. But dysfunction and oppression, alcoholism are a way of life here.” Our interview ends abruptly, interrupted by a phone call. Red Hawk apologizes; he has to leave for the funeral of a child in a neighboring town. For the rest of the week, a sign hangs in the Buffalo Jump window: “Gone to funeral.” I head off to check in to a hotel.

‘For tribes here, health care is a right. They were promised health care “for as long as the river is running.”’

The next morning, I wake to the sound of native drumming from the radio alarm clock. I’m staying in the Quality Inn Rosebud Casino near the Nebraska border, about 40 minutes from the hospital, and worry about finding my way there before dawn in the dark. The weather’s turned colder, spitting icy rain on the windshield of my rental car. Tumbleweeds skitter across the highway as dawn breaks, a long, thin orange line drawn across the horizon. There are few addresses on the reservation, mostly P.O. boxes; GPS rarely works, and cell phone service is spotty. Mostly I rely on friendly tips for directions.

The Rosebud hospital is a modern building constructed inadvertently on top of a rattlesnake nest, surrounded by open land. Patients travel sometimes 100 miles over rough roads to get here, though finding transportation often isn’t easy. Still, the 35-bed hospital is consistently over capacity. Getting an appointment can be difficult to near impossible because of a lack of staff and an overabundance of patients.

I join the Stanford students at the morning staff meeting, listening to Ira Salom, MD, chief medical officer, talk about impending cutbacks of about $200,000 due to the automatic budget cuts known as sequestration which have hit the already underfunded Indian Health Service hospitals and clinics especially hard.

“We’re looking for quarters under seat cushions,” says Salom, who was recruited to the hospital from New York City where his wife still lives. “If I don’t make these cuts soon, we’re going to run out of money.” A staff member pokes his head into the room to inform him that the technician who runs the CT scanner is out sick with a migraine, leaving no one to fill in. Also, there’s no night staff available to cover the first week of April in the ER. He sighs and turns the meeting over to the chief pharmacologist, who discusses options for cutbacks, such as lidocaine patches, Lubriderm lotion and statins — non-lifesaving supplies.

The Rosebud hospital is run by the Indian Health Service, which is part of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. The IHS is responsible for providing health care to 2 million Native Americans and Alaskan Natives who belong to more than 557 federally recognized tribes in 35 states. It was set up by the federal government to honor a long history of treaties in which Indian tribes exchanged land with the United States in return for food, education and health care.

“For tribes here, health care is a right,” says Sophie Two Hawk, MD, CEO of the hospital and the first Native American to graduate from the University of South Dakota medical school, in 1987. “They were promised health care ‘for as long as the river is running.’”

It’s well-documented that the government’s attempts to meet its obligations to the Native Americans have failed miserably; the primary cause is insufficient funding. Currently, prisoners receive significantly higher per capita health-care funding than Native Americans. The U.S. Commission on Civil Rights reports the federal government spends about $5,000 per capita each year on health care for the general U.S. population, $3,803 on federal prisoners and $1,914 on Indian health care.

One of the most pressing inequities of the federal government’s attempts to meet these obligations, according to advocates such as the National Indian Health Board, a nonprofit in Washington, D.C., is that while the biggest federal health and safety-net programs such as Medicare, Social Security and veterans’ health are protected from sequestration cuts, the IHS is not. It stands to lose 5 percent of its $4 billion budget this year, a percentage that is expected to increase next year if sequestration continues, IHS administration officials say. These cuts will be devastating for many tribes.

Other Native health-care advocates, led by the Association of American Indian Physicians, push for greater funding for the federal government’s student loan program for health professions.

‘If someone shows up with a torn ACL, we can’t afford to fix it. He will walk with a limp.’

“One of the main goals of the AAIP is to increase American Indian representation in the health-care workforce,” says Nicole Stern, MD, AAIP president and Stanford University graduate, who points to the perpetual labor shortages faced on reservations, which hover at 15 to 20 percent for physicians.

IHS administrators say they are hopeful that the passage of President Obama’s health-care law, the Affordable Care Act, will ease these ongoing budget and staff shortages. The law, which began providing government-subsidized insurance plans Oct. 1 to low- and middle-income individuals, makes permanent the reauthorization of the Indian Health Care Improvement Act, which authorizes Congress to fund the Indian Health Service — a positive step, Native health advocates say.

Also, by providing health insurance to many of the same low-income patients that the IHS currently cares for, the new law should allow the IHS to seek reimbursement for services that it would otherwise pay for itself.

“The act should free up more funding for referred inpatient and specialty care,” says Margo Kerrigan, California area director of the IHS. “We hope it does, but Indian people will need to apply for these alternate resources.”

One afternoon during a visit to the hospital, I walk from the ER to a separate wing to find the CEO, Two Hawk. Her door’s ajar, and she waves me in. She’s dressed in the military-style uniform of the U.S. Public Health Service Commissioned Corps, her long, gray hair pulled back in a braid that drops down her back. She’s doing paperwork — denying a pile of requests from her physicians for additional care for their patients. The requests are appropriate, she says, but the hospital just doesn’t have the money to pay for the care.

“If someone shows up with a torn ACL, we can’t afford to fix it,” she says. “He will walk with a limp.”

Two Hawk, like many others, links the poor health statistics of Native Americans not only to the lack of adequate IHS funding but to the community’s tragic history. The hopelessness, the despair — it’s rooted in history.

For Rosebud, that history began in 1868 when under the terms of the Fort Laramie Treaty the Lakota Sioux, known as Sicangu, were placed on one large reservation that covered parts of North and South Dakota and four other states. After defeats in the Plains Wars of the 1870s, 7.7 million acres of Indian land were taken by the federal government and smaller reservations were created. The Sicangu Lakota were sent to live on the Rosebud Reservation. It’s a familiar story, repeated over and over again, throughout the American West: massacres, followed by relocations, followed by broken treaties. About 500 reservations remain today spread across the nation.

The term “historical trauma” is used to name the psychic wounding caused by massacre, destruction of culture and dislocation of the Native Americans in the name of Manifest Destiny. This history is still felt strongly on the reservation, Two Hawk says.

‘I grew up in a community where you are related to hundreds of people. We take care of one another. We perform ceremonies together. There are real deep ties with home.’

The forced relocation of Native American children to faraway boarding schools is a particularly ugly chapter in this history, which deeply damaged the Sioux. Native children were sent to boarding schools where they were forced to wear white man’s clothes and were beaten for speaking their native language. Almost every Lakota had a close relative who had been taken from home by white government agents in the early 1900s and sent to one of these schools. For decades, there were reports of abuse and malnourishment.

The long-term effects on health have been disastrous. The National Rural Health Association in a 2006 study reports: “The forced relocation of children into Bureau of Indian Affairs boarding schools ... led to cultural distortion, physical, emotional and sexual abuse, and the ripple effect of loss of parenting skills and communal grief.”

Leaving Two Hawk, I head to the office next door where another Native American hospital employee, psychologist Rebecca Foster, PhD, works. When I knock on her office door, she’s taking a break to cradle her week-old grandson. Foster and her husband, Dan, also Native and a psychologist at the hospital, have 14 children — seven of those adopted from relatives on the reservation who were unable to care for them. All seven of those children are special needs, like the baby’s father, who was born with fetal alcohol syndrome.

Foster’s goal was always to get an education, then return to help her people. She has served as a role model over the years. Young people gape at the degrees she’s hung on office walls, she says.

“They are always amazed to see a Native person who has accomplished things. I went to reservation schools. My parents stressed education. We came back to the reservation. ... There are a lot of very positive and wonderful things on the reservation, the strength of the community’s ties, the connections with ceremonies and traditions. I grew up in a community where you are related to hundreds of people. We take care of one another. We perform ceremonies together. There are real deep ties with home.”

She, too, attributes much of the destitution and despair on the reservation to history.

“I’m Blackfeet Dakota, from Montana,” she says. “We had Glacier Park. The government took it. The population was decimated from 60,000 to 6,000 from disease. ... We are the only group in the U.S. still under the jurisdiction of the federal government. We didn’t become U.S. citizens until 1924; freedom of religion was not granted until 1978.”

Tribes like the Sioux that followed the buffalo lost both their way of life and their food source due to western expansionism. Forced to live on the most desolate land and to turn to unfamiliar agrarian lifestyles, they were left with food from the government’s commodity program — flour, pasta, rice, peanut butter, canned food — a diet distributed from warehouses on reservations, devoid of fresh food. Today, it’s still nearly impossible to find fresh fruit and vegetables on the Rosebud Reservation.

The relocations of masses of people onto the least profitable lands in South Dakota have resulted in some of the lowest living wages in the country. The average family income is $18,000. Housing is poor, with family members crowded into unheated trailers; there are few jobs beyond some in minor agriculture and ranching; the difficulty recruiting teachers to the isolated location has resulted in poor schools with high school dropout rates of 50 to 60 percent. For the few Natives who do make it to college throughout Indian Country, a staggering 98 percent return within the first two months, homesick for the close community and culture that doesn’t exist for them in the outside world.

“I see a lot of kids who are depressed, who talk about suicide,” she says, then pauses to look into the eyes of her grandbaby. “And yet, kids are still resilient. They still have a desire to have a good life, to be happy, to accomplish things. No matter where you come from, you can never completely destroy that. There are very few kids here who don’t have a dream.

“What I tell young people is that there is a difference between having to stay here because you are trapped and choosing to be here because you have something to give. One’s a prison, the other is a home.”

Nearing the end of the week, the Stanford students make bison fajitas for dinner at their dormitory and discuss their experiences — the good and the bad, the tragic and the heroic.

“It opened my eyes,” says Roxana Daneshjou, an MD/PhD student. “I don’t think I had a very good understanding of what living on a reservation was like. It was shocking. Just seeing a health-care delivery system not working. We are not taking care of our people.”

Daneshjou talks about the patient she helped treat who had returned to the hospital after suffering a severe fracture in her arm two months ago. Because of the lack of orthopedic care, the patient was back again, her arm still in pain.

“It’s just awful. If we were at Stanford, she’d go see a very good orthopedic surgeon and it would be fine. It’s the worst feeling in the world to know that the ability exists to fix something, and just not see it get done.”

But undergraduate Layton Lamsam, Osage, who grew up getting care at Indian Health Service clinics on a reservation in Oklahoma, felt differently about his day. The hard-working, short-staffed professionals who provided the best care they could in some of the worst circumstances impressed him. His goal: to help improve this care someday.

During my flight home, my thoughts wander back to the Buffalo Jump Cafe and a 15-year-old Native American girl who walked in just before I left, a pink-strapped travel bag thrown over her shoulder. Two years ago, the girl had threatened to hang herself. School officials sent her to Shane and his wife to talk. She joined us at our corner table. When I asked about suicide, she covered her face with her hands. Tears leaked slowly between her fingers.

Since she was too upset to talk, we left the cafe to walk around the neighborhood, past the worn-out drunks, the church, the high school basketball courts. She’s more hopeful about the future now, she said. She’s thinking about becoming a nurse. But it’s hard to get to school most days. She lives with a large family in a small home with little money. Alcohol use is high, and family support low. She desperately wants to leave the reservation some day. But, then again, this is her home. It’s all she’s ever known.

“This is where my heart is, where I belong,” she said. “Of course I want to leave. But I want to come back and help my people.”

The wide open prairies disappear from my view as the plane takes off, and I catch my breath at the memory of the beautiful landscapes on the Rosebud Reservation and the brave people left behind there — at the end of a highway, down a road, around a bend — fighting hard for a brighter future.

Native health 101

Learning about a community in crisis

A Stanford Medical School course that began five years ago with a couple of students making a spring-break road trip to volunteer at the lone hospital on the Rosebud Indian Reservation in South Dakota has grown into a career-changing experience for undergraduates and medical students alike.

That first trip eventually transformed into a quarter-long class on rural medicine and the causes behind the heavy disease burden of Native Americans.

The heart of the course remains a weeklong trip to Rosebud, a destitute community with skyrocketing diabetes, alcoholism and suicide rates, and a life expectancy for males in the upper 40s, about 30 years lower than the U.S. average. Students spend the week building low-income housing and volunteering at the Indian Health Service hospital. The week inevitably puts a human face on the facts and figures they’ve studied and takes hold of the imagination of the students who travel there.

“The question often arises, what can you do in just one week?” says Krishnan Subrahmanian, MD, a graduate of the School of Medicine, who co-founded the course with Stanford medical student Shane Morrison. On the first trip to the reservation, where Subrahmanian had worked for two years previously as a high school teacher, they invited a few friends from their medical school class. The week made such an impression on them both that they worked to make it an official class.

“A week can start a month can start a year can start a lifetime of work,” Subrahmanian says.

Morrison says the experience influenced his choice of “scholarly concentration,” the individualized study program each medical student must complete. “My concentration is community health because of this trip,” he says. He’s seen the trip change the course of careers for other students as well, from undergraduates who decided to attend medical school to a law student who plans to work on alternative energy issues relevant to Native communities.

The two have since handed over the course to other students to lead. This year’s instructors were medical students Keith Glover and Adrian Begaye, both tribal members of the Navajo Nation. They see the course as key to teaching future doctors about the overwhelming needs of underserved communities such as Native Americans.

“One week can’t fix things,” says Begaye. “But we can come to a greater understanding of the needs of underserved populations and influence the course of some students’ careers.”