FALL 2013 CONTENTS

Home

Hello in there

Seeing the fetus as a patient

Gone too soon

What's behind the high U.S. infant mortality rate

The children's defender

A conversation with Marian Wright Edelman

Too deeply attached

The rise of placenta accreta

Labor day

The c-section comes under review

Changing expectations

New hope for high-risk births

Inside information

What parents may – or may not – want to know about their developing fetus

DOWNLOAD PRINTABLE

ISSUE (PDF)

In Brief

Genetic Adam and Eve on a date?

I thought you looked familiar

By Krista Conger

Art By Biophoto Associates

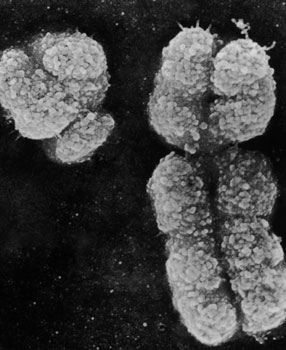

Y chromosomes are useful for tracking ancestral relationships. This electron micrograph shows a Y chromosome (left) and an X chromosome.

It’s tempting to imagine our two most recent common ancestors — sometimes referred to as Y-chromosomal Adam and mitochondrial Eve — skipping through the tulips hand in hand. The illusion is fueled by the recent discovery that the two lived during roughly the same time period. Very, very roughly, that is: The man lived between 120,000 and 156,000 years ago, the woman between 99,000 and 148,000 years ago.

It’s clearly unlikely that they knew each other. But that they could have lived at the same time comes as a surprise. Previous research had indicated that the man lived much more recently than the woman, says Stanford professor of genetics Carlos Bustamante, PhD, who in August published a study in Science on our most recent common ancestors.

Despite the Adam and Eve monikers, these people weren’t the only man and woman alive at the time or the only people to have present-day descendants. They simply successfully passed on specific portions of their DNA through the millennia to most of us, while the corresponding sequences of others have largely died out.

The crux of the new study was a comparison of Y chromosomes of 69 men from around the globe to create highly accurate inheritance trees. The researchers also studied the DNA in these men’s mitochondria — structures that serve as cells’ power plants and carry their own DNA.

Bustamante focused on these particular sequences because of the unique way they are inherited: The Y chromosome is passed only from father to son; the DNA in mitochondria is passed from a mother to her children. Both are useful for tracking ancestral relationships because they undergo much less of the shuffling and swapping of genetic material that occurs routinely in most human chromosomes.

What does the apparent overlap between the male and female sequences mean? It’s possible that it indicates a time when only a few sequences were passed on after others died out because of an unknown external event. A catastrophic volcanic eruption? A deadly virus? But it’s also quite possible that the timing is simply a fluke.

E-mail Krista Conger