FALL 2012 CONTENTS

Home

Bottom line

Medicine's Funding Pool is Drying Up

The competition

On the hunt for research dollars

Against the odds

A band of rebels fights to save health care

Giving well

Philanthropists roll up their sleeves

Melinda Gates on family matters

A conversation about contraception

Testing testing

Why some cancer screenings stir such controversy

DOWNLOAD PRINTABLE

ISSUE (PDF)

in Brief

Virtual Life

The first fully simulated organism

By Max McClure

Photography by Markus Covert

Mycoplasma genitalium is not an ambitious organism. Historically, the tiny bacterium has been content to quietly parasitize the human urethra. But having a genome an eighth the size of E. coli’s affords you certain privileges — such as being the first living thing to be completely reproduced, down to the last molecular interaction, in a computer.

The man behind the virtual microbe, assistant professor of bioengineering Markus Covert, PhD, isn’t particularly interested in M. genitalium. He’s concerned with biologists’ ability to fully understand the reams of data it’s producing. Faced with the interactions of hundreds or thousands of genes, how do you know what experiments to perform next?

“No one person can wrap their mind around every fact,” Covert says. Even the computational model of M. genitalium required over 1,900 parameters from more than 900 research papers. “So you make a computational model and use that to drive your experimental program.”

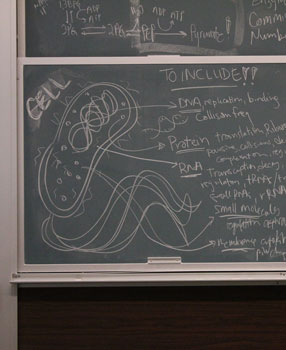

The Covert lab built its digital parasite by modeling individual biological processes – protein synthesis, cell division, etc. — as separate “modules,” each governed by its own algorithm. These modules then exchanged data after every cycle, making for a unified whole that very closely matched M. genitalium’s real-world behavior.

The team has already used the modeled cell, which it described in a paper published July 20 in Cell, to address questions about the bacterium's biology that have been too complex to approach with standard laboratory experiments.

“If you use a model to guide your experiments, you’re going to discover things faster. We’ve shown that time and time again,” says Covert.

But the researchers’ ultimate goal is something bigger: a biological version of computer-aided design, or CAD. The technology that allows engineers to mock up a new airplane fuselage on a desktop computer could allow bioengineers to rationally design entirely new micro-organisms.

According to co-author and Stanford graduate student Jonathan Karr, the only thing that’s keeping CAD out of the life sciences for now is the lack of more modeled organisms. “This is potentially the new Human Genome Project.”