FALL 2012 CONTENTS

Home

Bottom line

Medicine's Funding Pool is Drying Up

The competition

On the hunt for research dollars

Against the odds

A band of rebels fights to save health care

Giving well

Philanthropists roll up their sleeves

Melinda Gates on family matters

A conversation about contraception

Testing testing

Why some cancer screenings stir such controversy

DOWNLOAD PRINTABLE

ISSUE (PDF)

Plus

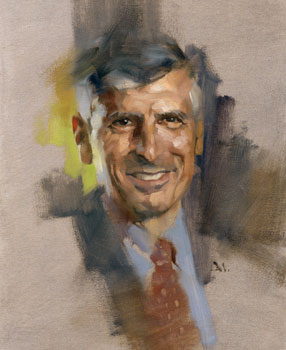

Marathon Man

Philip Pizzo nears the end of his remarkable run as dean

By Susan Ipaktchian

Illustration by Gregory Manchess

They say life is a marathon, not a sprint. That’s literally the case for Philip Pizzo, MD.

For most of the past 30 years, Pizzo has run 50 to 70 miles a week and entered two or three marathons (including the Boston Marathon) each year. That level of commitment on its own is commendable, but is even more remarkable considering his job – leading one of the top medical schools in the country.

Distance running holds a particular appeal for those like Pizzo who want to determine their own destiny. How fast and how far they go is determined by how well they’ve prepared. And the training takes time and discipline. They’re the only ones tracking their times, their distances and their progress.

Runners get a high from seeing just how much they can push themselves. And they often speak of how the solitude of running replenishes their ability to deal with other aspects of their lives.

Pizzo began running when he was 30 in part to lessen the affects of the asthma he developed as a child. But running became more than just a way to improve his health. “It gives me a sense of stamina and the ability to do my day job because I know that I’ve been through so many different physical challenges that I can probably sustain myself through some of the emotional and mental ones,” he says.

While the mentality of distance running remains firmly embedded in Pizzo’s approach to life, right now he’s focused on the art of passing the baton. As he prepares to step down after 12 years as dean of the School of Medicine, Pizzo seeks to make a smooth handoff to his successor, Lloyd Minor, MD, who will take over on Dec. 1.

He’s passing on the leadership of a school that that has experienced a rebirth of sorts in the past decade, with new organizational structures that have strengthened the collaborations between basic scientists and clinicians. Morale has improved, the faculty has become more diverse and the biggest building boom since the school moved to the Stanford campus in 1959 is well under way.

While this will be another finish line for Pizzo, he’s already scouting for the next course and new challenges. “This is definitely not a path toward retirement,” he says. “It’s a path toward transition and renewal.”

On the personal side, that means more time with his wife, children and his grandchildren, who refer to him as “Indy,” after the intrepid Indiana Jones character. Professionally, he’s looking forward to plunging more deeply into clinical and academic endeavors. And physical renewal is on the menu as well. Since April, he’s been rehabbing his back to counter the effects of less-than-ideal posture and inattention to “core training” over the years. “I’m in a musculoskeletal repair situation,” he says ruefully, but quickly adds that once he’s recovered, he’d like to train for a 50- to 100-mile ultramarathon.

“People question my sanity, but you have to have a goal, right?” he says.

The training

Pizzo was born in New York City in December 1944 to working-class parents who immigrated from Sicily. Finances were tight for the family of four (he has a younger brother, Michael). “I lived through the eyes of discoverers, inventors and heroes whom I encountered through reading books,” he recalls.

As a teen he was already drawn to science, and conducted experiments down the street in his aunt’s garage after his mother deemed them “too messy” for the family’s home; they involved mice purchased from the local pet store.

Pizzo earned scholarships that enabled him to attend Fordham University and became the first person in his family to graduate from college. Then it was on to the University of Rochester for medical school. While working toward his medical degree, he married Peggy Daly in 1967, who went on to a distinguished career in early childhood education and public policy. (She is a senior scholar in Stanford’s School of Education.)

Contemplating his future in medicine, he knew he wanted it to encompass patient care as well as research. “I’ve always been the kind of person who put one’s heart and soul into asking, ‘What’s the big question? What’s the big problem?’”

When he graduated in 1970, he served his residency in pediatrics at Children’s Hospital in Boston where he began to focus on infectious diseases and cancer. While there, he read a paper tracking fevers in adult cancer patients, and decided that similar work was needed to understand how fevers affected children with cancer. “This led to a review of 1,000 charts in the record room at 4:30 each morning, and the first report of 100 cases of fevers of unknown origin in children published in Pediatrics,” recalls Fred Lovejoy, MD, who was chief resident at the time and is now a professor of pediatrics at Harvard. “This resulted in a lead authorship for Pizzo, with his chief resident – me – buried in the middle,” Lovejoy adds with a laugh

Pizzo’s clinical research examined a wide range of issues involving infection and fevers in children whose immune systems were compromised by cancer, and helped identify the best ways to treat the infections.

After completing his residency, he went on to a fellowship in pediatric oncology at the National Cancer Institute where he continued both his clinical work and his research. Working with children facing cancer diagnoses helped Pizzo hone the communication skills that have persisted throughout his career. “As a pediatric oncologist, I had to learn very clearly the art of listening and of being honest, and of being able to share news and information with mothers and fathers and families in a way that always bore integrity and honesty,” he says. “You learn never to walk away and leave the words unsaid that need to be said, and to say them with a sense of compassion and sensitivity.”

Reflections on the dean

‘He believes strongly in the worth and value of fellow human beings. He is totally dedicated to children. To see him interact with patients and their families is to see a truly wonderful person. He wears his heart on his sleeve – it’s right out there for all to see.’

– David Poplack, MD, director of the Texas Children’s Cancer Center and professor at the Baylor College of Medicine

When his fellowship ended, Pizzo got a full-time position at the NCI, first as an investigator in pediatric oncology, then heading the pediatric infectious-disease section. It was during this time that the AIDS epidemic began to unfold.

“At that time, the NCI focused on cancer,” says David Poplack, MD, director of the Texas Children’s Cancer Center and a professor at the Baylor College of Medicine. The pair had served their residencies together in Boston and then worked at the NCI. In 1989, Pizzo and Poplack published what has become the definitive book on cancer in children, Principles and Practice of Pediatric Oncology, now in its sixth edition.

“Phil realized we were one of the few centers that had a scientific focus that could and should focus on HIV,” Poplack says. “He influenced the NIH leaders to take on the care of pediatric HIV cases, and the new retrovirals to treat HIV were developed in that setting. His absolute devotion to treating HIV disease in children and finding answers was incredible to witness.”

Caring for patients, carrying out clinical research, authoring books and papers, mentoring trainees. It was a heavy workload, but colleagues say Pizzo did it with charm, grace and a deep well of empathy. “I used to try to keep up with him, but I finally said to hell with it,” says Poplack. “People consider me a workaholic, but I don’t even rate at the lowest level of the Pizzo scale.”

Stretching

Pizzo describes himself as “a product of the 1960s.” He saw his role going beyond clinical practice, teaching and research. “I’m one of those people who really thought that you could change the world, make it a better place, through one’s commitment, zeal and activities,” he says. While at NIH, Pizzo also learned how to be an effective advocate as he reached out to lawmakers, regulatory agencies and influential figures to raise funds and promote awareness.

“When President Reagan came to NIH and visited our ward, Phil took him on rounds and was holding a baby who had HIV. He said, ‘Here, Mr. President, why don’t you hold him,’ and literally handed the baby to Reagan,” Poplack recalls. At the time, many in the public viewed those with the disease as pariahs, and AIDS activists were criticizing Reagan for failing to forcefully address the growing epidemic. Poplack says he nervously watched, afraid Reagan would refuse to hold the baby Pizzo was proffering. “And just the opposite happened – Reagan embraced the child. The next day, there was a photo of Reagan with the baby in The New York Times. I think it did more to de-stigmatize the disease than any other photo.”

Pizzo’s advocacy eventually extended to developing the Best Pharmaceuticals for Children Act, enacted in 2002, to promote clinical trials for children. He also raised funds for and established the Children’s Inn, which houses the families of children being treated at the NCI, and Camp Fantastic, a weeklong camping experience for children who have completed their cancer treatments. The camp just celebrated its 30th anniversary.

He also met Elizabeth Glaser, who contracted HIV through a blood transfusion and unknowingly passed on the disease to two of her children. Glaser formed the Elizabeth Glaser Pediatric AIDS Foundation in 1988 to help spur research and funding for the disease; Pizzo was one of the first members of the foundation’s health advisory board, and later a member of its board of directors.

And despite the many demands on his time, Pizzo willingly offered his help to other physicians with perplexing cases. One young doctor who sought him out was Charles Prober, MD, who had recently started a pediatric infectious disease position in Toronto. When he had patients who had infections complicated by cancer, he remembered reading Pizzo’s papers and called the NCI to seek his advice. “He got back to me extraordinarily quickly and personally,” says Prober, now a professor of pediatrics at Stanford. “He took such an interest and really wanted to help me find the best answers to my questions. That personality trait – of being so responsive to queries from anybody at quite literally any time – has always been a part of his life.”

By 1996, Pizzo had been at the NCI for 23 years, serving for 15 of them as chief of pediatrics. He had collaborated with physicians and researchers throughout the world, and helped contribute to the significant gains in treating cancer and infectious diseases in children. But he wanted to spend more time training and mentoring the future leaders of pediatrics, and so in 1996 he went to Harvard where he chaired the Department of Pediatrics.

And then one of his long-distance mentorships helped steer him across the country.

The Starting Line

In 2000, a search committee was looking for a new dean at the Stanford School of Medicine. Though Stanford has always enjoyed a strong reputation as a research-intensive medical school, spirits were low on the campus. Stanford and UC-San Francisco had attempted a merger of their clinical enterprises that ultimately proved unsuccessful, and the costs from the failed effort had been heavy. Additionally, the school was facing potential sanctions from the Liaison Committee for Medical Education, which accredits all U.S. medical schools, for its inadequate classroom and library facilities.

Reflections on the dean

‘Phil Pizzo has been a remarkable dean of the School of Medicine, most notably for his support of basic research, and for being the spark plug for scientific discovery and technology development and their impact on translational medicine.’

– Lucy Shapiro, PhD, director of Stanford’s Beckman Center for Molecular and Genetic Medicine

Prober, who wasn’t a member of the search committee but often played golf with University President John Hennessy, PhD, mentioned that Pizzo would be a good candidate. (Prober adds that he and colleague Ann Arvin, MD, professor of pediatrics and the university’s vice provost for research, still jokingly argue over which of them was the first to suggest Pizzo’s name to the committee.)

Pizzo says that when he was approached about the Stanford deanship, he saw the possibility of helping to train medical leaders in fields beyond pediatrics. And he also saw a tantalizing challenge.

“Stanford was an institution that was rich in heritage, extraordinary in terms of its intellectual capital, but was also trying to recalibrate where the medical center was going,” he says. “That is what always drives my personal passion. It’s about trying to craft a future agenda, project it, think about it and then try to move toward it.

“I also realized that this was a world – Palo Alto, Silicon Valley, Stanford – that didn’t have ‘can’t be done,’ in its lexicon. That aspiration of taking on the challenges and not letting ‘no’ get in the way is, to me, the driving force of this institution.” He accepted the job, and likes to point out that he began serving as dean on April 2, 2001; he didn’t want to start on April Fool’s Day.

One of Pizzo’s first actions as dean gave a clear sense of his leadership style. In the preceding years, school officials had been working on plans for a new education building that would address the Liaison Committee for Medical Education’s concerns about classrooms and library facilities, and had a deadline of 2001 for implementing the plan. But as Pizzo took stock of the effort, it became clear that few were happy with the way the plans were shaping up. Nonetheless, they felt they needed to proceed to satisfy the LCME.

Pizzo put the brakes on the plan, asking for a new analysis and an approach that would truly serve the future needs of Stanford’s medical students. He convinced the LCME to give Stanford more time. “Many people in his situation would have said, ‘Oh, well, we are moving in a direction that’s needed and so let me hop on that train and see where it goes,‘” says Prober. “But that is not his style. He carefully re-analyzed everything, thought about the optimal direction for the facility and set about raising the money and building it.” The resulting building, the Li Ka Shing Center for Learning and Knowledge, opened in 2010. In addition to state-of-the-art classrooms and training technology, it houses the dean’s offices and serves as the school’s official front door.

Pizzo was also aware that his background in clinical research made the school’s basic scientists uneasy. “When he came, there was a certain suspicion that perhaps he would not be very supportive of basic science,” says Nobel laureate Paul Berg, PhD, professor emeritus of biochemistry. “But now I don’t think there’s anybody who doubts for a moment his commitment to and support of the basic sciences.”

But the biggest need Pizzo wanted to address was morale and reducing the fragmentation that he saw. In addition to the low spirits in the wake of the de-merger with UCSF, Pizzo sensed that many faculty didn’t feel much kinship with the larger community at the School of Medicine. He wanted to encourage greater connections between basic and clinical scientists, between staff and administrators, between the school and the two hospitals, and between the medical center and the university.

But the biggest need Pizzo wanted to address was morale and reducing the fragmentation that he saw. In addition to the low spirits in the wake of the de-merger with UCSF, Pizzo sensed that many faculty didn’t feel much kinship with the larger community at the School of Medicine. He wanted to encourage greater connections between basic and clinical scientists, between staff and administrators, between the school and the two hospitals, and between the medical center and the university.

One of his first steps was to organize a retreat at which the full spectrum of the medical center and university were represented. He has often recounted how, at the first year’s gathering, the basic scientists clustered on one side of the room while the clinicians were on the other. But as the weekend progressed, relations thawed. “People began saying to each other, ‘I think I see now what your role is better than I did before. I think I see why basic science is so important to the future of clinical care,‘” he says. “They began to galvanize as a community, and the school became something that people wanted to be part of, that they wanted to contribute to.”

Pizzo used the discussions and work from that meeting to draft a master plan for the medical school, a document titled “Translating Discoveries,” and held a series of town hall meetings to get input from the broader school community. Several of the recommendations were already being put into action by the time the second annual retreat rolled around. This time, Pizzo says, there was much greater interaction among the participants.

This deliberate outreach is one of the hallmarks of his leadership style. “I’m pretty clear about saying, ‘These are the things I think we should take on and challenge,’ and then learning from the responses of others who critique it and help to reshape it. It’s a top-down, ground-up fusion style,” Pizzo says. “I’ve viewed my role as being a steward – hopefully more in the background than foreground – in trying to move or stimulate or catalyze ways of going forward, which others would then carry on.”

That forward progress covered all fronts. In research, Pizzo created the school’s Institutes of Medicine – five organizations that span a variety of departments and disciplines in order to move discoveries from the bench to the bedside, and link the school’s researchers to their counterparts in clinical programs at Stanford Hospital & Clinics and Lucile Packard Children’s Hospital.

Reflections on the dean

‘I’m a strong admirer of Phil’s. Over a period of time, you just fall in love with the guy. His tenure here has been the most productive and transformative time in the history of the medical school on the Stanford campus.’

– Paul Berg, PhD, Nobel laureate and professor emeritus of biochemistry

Pizzo also worked closely with the CEOs at the two hospitals to dramatically increase the number of physicians and physician-scientists on the faculty, while also focusing on the quality and service of the medical care being delivered. One of his highest priorities has been making sure that the quality of the medical center’s patient care matches the school’s long-standing record of excellence in research.

Ann Weinacker, MD, who has been chief of staff at Stanford Hospital & Clinics since 2011, can attest to Pizzo’s concern for patients. She recalls that in December 2008 she went to Pizzo to find out how to better serve the medical school. He had just finished writing an issue of his twice-monthly newsletter, and one topic he addressed was making sure that physicians saw their patients as human beings, not simply as an illness or injury to be treated, that patients didn’t get “lost” in the complex academic medical environment, and that they knew who their doctors were. Weinacker and Pizzo brainstormed about how to ensure compassionate care. Weinacker began meeting with three other medical service directors to devise strategies for “treating patients as we would want to be treated, seeing them as people who are often vulnerable, but always deserving of being empowered to make decisions about their own care.”

That effort has since grown and been embraced by hospital leaders, Weinacker says. “Dr. Pizzo’s been 1,000 percent behind this whole thing – making sure that patients are treated not just appropriately in medical terms, but also appropriately as individuals, as people who deserve the best we have to offer,” she says.

On the education front, he played a leading role in revising the curriculum for medical students to further solidify Stanford’s goal of creating the next generation of leaders in academic medicine. In addition to better integrating classroom learning with clinical training, the new curriculum required medical students to complete a scholarly concentration in which they select a specific aspect of medicine for multiyear study. And to ensure that the students will be excellent clinicians as well as top-notch researchers, the school implemented the Educators-4-Care program to provide students with ongoing training in the doctor-patient relationship throughout their time at Stanford.

Pizzo also aggressively advanced the effort to improve diversity at the school, creating the Office of Diversity and Leadership and appointing Hannah Valantine, MD, to implement programs to attract and retain a professoriate that reflects the nation’s diversity. For instance, Stanford previously lagged behind the national averages and its peer institutions in the number of women faculty at all ranks. Today, Stanford is well ahead of its counterparts and the national averages.

He also implemented programs to ensure that the integrity of the medical school and its employees remained above reproach. This included prohibiting faculty members from accepting industry gifts of any size, including drug samples, and from participating in speakers’ bureaus in which they are paid to deliver company-prepared presentations on drugs, devices or other commercial products. The school also declined to accept support from pharmaceutical or device companies for specific programs in continuing medical education.

The industry-interaction policies didn’t sit well with many faculty members, but Pizzo was adamant. “I want to be able to honor the public trust,” he said in 2008 when the CME policy was announced.

There were also a few actions that represented his personal concerns about health and safety. He spurred a policy that prohibits smoking throughout the medical center, and readers of his newsletter often saw his admonitions for bike riders to wear helmets.

“He’s a grandma,” Berg quips. “He’s got to take care of everybody.”

And that caretaking extends to the personal level. Without fail, those who know Pizzo remark on his genuine interest in the people he meets and works with. He remembers details about their lives and their families, and is the first to offer help.

Berg cites an incident involving a colleague who was briefly hospitalized in San Francisco after an accident. When Berg became concerned that the colleague was being discharged too quickly and might need further attention, he called Pizzo for advice. “In 15 minutes, Phil called back and he had already talked to our trauma center so that they could follow up [with the patient], and he explained how these kinds of cases are typically treated,” Berg says. “I know he was just getting ready to go into a long conference call, and yet he got right back to me. He really cares about people; it’s extremely sincere.”

Setting the pace

As the demands of running a medical schools are many, it would’ve been understandable for Pizzo to step away from any type of clinical duties. Yet he has continued to be involved in weekly teaching rounds with medical students, and takes a week or two each year to spend time in Packard Children’s Hospital, treating children with infectious diseases. “It’s a way of reaffirming my role as a care provider,” Pizzo says. “During the time that I’ve been at Stanford as dean, it’s been a way of communicating to colleagues that I am able and willing to do some of the same difficult work that they’re doing.”

He also made the deliberate decision to steer clear of board positions with pharmaceutical or biotechnology companies, preferring to avoid anything that might cast suspicion on his integrity or the school’s.

Reflections on the dean

‘Visionary. Determined. Focused. Loves a challenge. These are a few words that come to mind when I think of Phil Pizzo.’

– John Hennessy, president of Stanford University

“Phil is an extremely moral person, and morals and ethics go together,” Berg says. “I think if anything would really upset him, it would be somebody who violates an ethical or moral principle.”

Pizzo’s years as dean also coincided with the controversy over stem cell research. He expressed concern when then-President George W. Bush imposed severe limits on federal funding for embryonic stem cell research, and began looking for alternate ways of continuing the work. That, in part, led to the creation of the first of Stanford’s five institutes, the Stanford Institute for Stem Cell Biology and Regenerative Medicine. When California voters approved Proposition 71 in 2004 to provide $3 billion for stem cell research, Pizzo was the first person named to the oversight committee for the state’s new stem cell agency.

The state’s support for stem cell research also figured into the overall plans for replacing the school’s aging facilities. The classrooms and laboratories first built when the medical school moved to the Palo Alto campus in 1959 weren’t adequate for today’s research and technologies. As Pizzo and his team worked on the new educational facilities, they also developed plans for other research buildings that would allow for the kind of interdisciplinary collaboration envisioned by the school’s institutes. The first of these facilities, the Lorry I. Lokey Stem Cell Research Building, opened in 2010.

The results

Looking back on the past 12 years, the physical changes to the medical school campus – the new buildings – are the easiest to see. And there is a long list of other accomplishments. The number of faculty at the medical school has risen to 872 (from 710 at the time Pizzo arrived), and more than 600 of them have been hired during his watch. Additionally, the school has gone from the $245 million in sponsored research in 2001 to the $498 million the school earned in fiscal year 2011. Under his leadership, the school also secured approximately $1.6 billion in philanthropic support. And the school and the two hospitals continue to work strategically to provide excellent service and look for ways to enhance value while reducing health-care costs.

But Pizzo measures his success by a single yardstick – greater cohesiveness among the faculty, staff and students.

“If the members of our community feel prouder to be here, and be members of the Stanford community, today, compared with a decade ago, that is a wonderful and exhilarating accomplishment,” he says. “I’d like to think of them as years of catalytic and fusional change. A time when the community rallied around the sense of mission – translating discoveries, building on new knowledge, fostering the creation of new approaches to education and to clinical care and its delivery. A time of really saying, How could we – as Stanford Medicine, as small as we are in the sphere of this nation’s medical enterprise – be a role model for change? How could we be a place that others will look at and say, ‘They’ve really done something important there. They’ve gotten it right’?”

That kind of atmospheric change is hard to measure, but those inside and outside the medical school attest to its reality.

“I think there’s been a real culture change in how people view their role in the medical school,” says Berg. “A feeling of being part of the medical school rather than being biochemists or developmental biologists is firmly entrenched. He really has created a sense of the School of Medicine being a principal focus.”

Hennessy, the university’s president, says Pizzo “anticipated research directions and reorganized the school’s research programs – transforming the medical school and raising the profile of Stanford Medicine. We celebrated the medical school’s 100th anniversary four years ago, and thanks to Phil’s leadership, Stanford Medicine is well-positioned for another century of pioneering discoveries.”

“When Phil Pizzo took over as dean, the morale in the School of Medicine, particularly in the clinical departments, was at an all-time low in the wake of the unsuccessful merger with UCSF,” says Provost John Etchemendy, PhD. “Through sheer force of will, Phil managed to right the ship and steer it in a new, more positive direction. He now leaves the school in the best shape it’s ever been – academically, clinically and physically – poised for even greater achievements to come. That is his legacy, and a remarkable one it is.”

Second wind

In the last few years, Pizzo began thinking more about the next phase of his life. His daughters – Cara, a pediatrician at the Palo Alto Medical Foundation, and Tracy, a program manager at Google – live nearby and have families of their own, and he relishes being a grandfather. Not quite ready to be called Grandpa, he asked his grandchildren to call him “Indy” after the movie character that first enthralled him 31 years ago. In fact, Pizzo displayed the character’s trademark fedora and whip on a wall in his National Cancer Institute office for years until someone took the whip. What appeals to him about Indiana Jones is “the opportunity for adventure, for outlandish – if sometimes heroic – acts that are at the edge of appropriateness, that dig into the past and maybe, in a way, transform a little bit of the future,” he says. “I also identify with a fear of snakes.”

Pizzo sees life as a series of cycles, and the belief that he was heading toward a new cycle began to crystallize as he presided over meetings in 2010 where a policy was being developed to help senior faculty with transitional career planning. “I looked around the room and realized that at 66, I was the senior member of the group and that if I was going to model this, I needed to engage with this on a personal level,” he says.

Ever the mentor, Pizzo says he also wanted to make sure his choices for the next stage of his life made it clear “that it’s OK to make a transition to something other than the next acquisition of power and stature and leadership. That it’s OK to say that you want to find a balance between your personal and your professional life. To me, it’s important to signal that becoming a senior member of a community is not a prescription for obsolescence. It’s an opportunity for recalibration.”

He is already scouting out a new course. On Dec. 1, he will begin a 12- to 18-month sabbatical in which he will reconnect with his academic and clinical roots in pediatric cancer and infectious diseases. He also plans projects both with Stanford’s Center on Longevity and the new Clinical Excellence Research Center, which aims to find ways to lower health-care costs while improving patient outcomes. He plans to do some writing as well as that possible ultramarathon once his back is fully healed. “And I might even indulge a long-held dream of learning to play the cello,” he says.

When he says “renewal, not retirement,” he clearly means it.

E-mail Susan Ipaktchian

1:2:1 Philip Pizzo

Listen to the interview.

Photo by Steve Fisch

Web Extra

View Slideshow