SPRING 2010 CONTENTS

Home

Little patients, big medicine

Getting serious about helping without hurting

Girls’ day out

Teens with cancer paint the town pink

Hand-me-down blues

Ending depression’s legacy

Paging mom and dad

The future of children’s hospitals

Mother Courage

Mia Farrow’s calling

The inner child

Art offers an opening

A most mysterious organ

Looking for answers about the fetus’s lifeline

DOWNLOAD PRINTABLE

ISSUE (PDF)

Special Report

Wishbone

Saving Mark’s arm

By Erin Digitale

Illustration by Bryan Christie

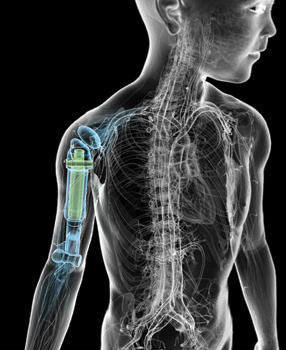

When 3-year-old Mark Blinder was diagnosed with a rare bone cancer, doctors gave his parents three agonizing options:

Amputate the affected arm at the shoulder, irradiate the tumor and risk a second malignancy, or try a limb-preserving surgery that had never been attempted on a toddler.

Sitting in a procession of doctor’s offices at Lucile Packard Children’s Hospital, Alla Ostrovskaya and Gene Blinder tried to concentrate in spite of their shock. Their son’s arm pain had been diagnosed months earlier as a bone infection, curable with antibiotics. “No one in our family had ever had childhood cancer,” Ostrovskaya says. But new tests showed a tumor growing through Mark’s entire right humerus, the long bone in the upper arm. Now that it was clear antibiotics weren’t the answer, the couple heard the pros and cons of each possible treatment.

Amputation was simple and would vanquish the tumor, explained orthopedic surgeon Lawrence Rinsky, MD. “But you can’t go back,” Rinsky told them. Radiation would preserve Mark’s hand but kill the growth plates in the affected bone, said pediatric oncologist Neyssa Marina, MD, leaving Mark’s upper right arm small and fragile. Radiation might also make the malignancy return, a particular concern because Mark’s diagnosis, Ewing’s sarcoma, recurs more often than most childhood cancers.

After a few rounds of chemotherapy, this tumor seemed to calm down. Mark stopped crying through the night with pain. He fell in love with his oncology nurses, calling out “Nurse, nurse!” in his most winning voice when he wanted an extra bit of attention.

The third choice sounded simultaneously best and worst: Rinsky offered to try replacing Mark’s diseased bone with a titanium implant that could be expanded as Mark grew. The cancer would come out, and the arm would be saved, but Blinder and Ostrovskaya would have to put their 3-year-old through an untried surgery with a long, painful recovery. And the artificial bone would have to be designed from scratch.

Ostrovskaya was heading into her last year of medical school when Mark was diagnosed in July 2008, and in some ways that complicated the decision she and her husband faced. For 12 years — first in Russia and then in the United States — she had devoted herself to learning the rhythms of medicine, learning that medical innovation progresses in cautious baby steps.

Except when it doesn’t. Except when someone sits you down and says, please let us do something radical to your youngest child. If you say no, we may have to cut off his arm.

In the past, it was considered nearly impossible to treat a small child’s humerus tumor without amputating. Scientists have struggled to devise cancer treatments that will save a limb and accommodate several inches of future growth in the upper arm, so many doctors simply call for amputation.

“Amputation was our last resort,” Ostrovskaya says. “We said, ‘We are not going to amputate if there is a chance to save his arm, because he is so little.’” Mark loved swimming, kicking a soccer ball, climbing the jungle gym, playing mini-golf and chasing his big brother, 7-year-old Tony; it was painful to think about such an active child losing a limb. And he was right-handed, Blinder says, which made the prospect of amputation even more dismaying.

So Marina started Mark on chemotherapy, the logical first step to preserve his arm. Chemotherapy alone wouldn’t vanquish the cancer, but it would reduce the tumor’s blood supply and give other treatments a head start.

“Most bone tumors are very vascular tumors — they’re angry,” Marina says. Bone tumors furiously spew out biological signals that spur growth of new blood vessels, bringing lots of nutrient-rich blood to feed the tumor’s rampage. Surgeons who attempt to remove these tumors prior to chemotherapy often find a welter of pulsating blood vessels obscuring their target. “Chemo makes surgery a lot simpler,” Marina says — kill the tumor, and the extra blood vessels shrink or disappear. Chemo was the logical first step before radiation, too.

After a few rounds of chemotherapy, this tumor appeared to calm down. Mark stopped crying through the night with pain. He fell in love with his oncology nurses, calling out, “Nurse, nurse!” in his most winning voice when he wanted an extra bit of attention. He began using his right arm again, freed from months of throbbing. On the oncology ward, Marina noticed him happily engrossed in computer games.

“It was hard because if we had just chosen radiation, not surgery, that would not have been as physically painful for him,” Ostrovskaya says, recalling how they considered their options while watching the improvement in their son. The parents had several conversations with Marina and Rinsky, consulted with an oncologist who specialized in pediatric radiotherapy, read everything they could find in the medical literature and talked the decision through several times. In the end, though they hesitated to put Mark through more pain, the long-term drawbacks of radiation seemed worse. Blinder told his wife, “It’s surgery and nothing else; if Dr. Rinsky said we can do surgery, he’s going to have surgery.” Yet even as they gave Rinsky the go-ahead, Blinder and Ostrovskaya still worried. The first-of-its-kind operation came with no guarantees.

Rinsky had mixed feelings about the surgery, too. When he first proposed the idea, he says, he remembers “sort of secretly hoping that there was some other way.” Surgically, amputation would have been much easier, but, like Mark’s parents, he wanted to save the little boy’s hand and arm. With just the right replacement bone, maybe the surgical team would have a shot. “There’s no pre-existing prosthesis for a child this small,” Rinsky says.

The prosthetic bone had to be small enough to fit in a 3-year-old’s arm, strong enough to last a lifetime and expandable to allow for growth. Rinsky knew that balancing these demands would pose a big challenge for engineers, especially because of the need for moving parts that would allow him to expand the prosthesis in later surgeries. On top of that, because Mark’s entire humerus had to be removed, the prosthesis could attach only to soft tissue — muscles, tendons and ligaments. Most bone prosthetics replace half of a bone and are cemented to healthy bone. Rinsky had to find another way to hook up this implant, while preserving as much function as possible in the shoulder and elbow joints.

The engineers went through several rounds of planning over a two-month period, sending Rinsky each iteration of the design. “They would show me something that I could not fit into the arm, and I would say, ‘I have to close the incision!’” he says.

He began collaborating with Indiana-based bone implant manufacturer Biomet Inc., sending engineer Aaron Smits X-rays of Mark’s arm, a list of the characteristics he hoped for in the finished prosthetic and a deadline that coincided with a logical point to pause Mark’s chemotherapy. Rinsky, who has no financial relationship with the company, had collaborated with Biomet before and knew its strong reputation for semi-custom prosthetic bones. He had confidence that they were right for this more complex job.

“The age and size of the patient presented an unusual challenge,” Smits says. “And what Rinsky was trying to accomplish by performing partial joint replacements on both the shoulder and the elbow was kind of unorthodox.” From an engineering standpoint, it would have been easier to replace Mark’s entire elbow with a metal joint, Smits says, but that would have required removing parts of Mark’s two lower arm bones, the radius and ulna, in addition to the humerus.

But Smits relished the challenge. He had come to prosthesis design almost by accident, when a college internship with Biomet made him realize he’d rather be building replacement body parts than engineering new cars. And he had already planned one-of-a-kind implants for other unusual patients: people with gene defects of bone formation, dwarfs with bony deformities and kids with rheumatoid arthritis.

Starting with designs for telescoping prostheses intended for larger patients, Smits and his co-workers began scaling down to produce a customized device for Mark. The boy’s humerus was 17 cm long; based on measurements of his parents’ arms, Rinsky estimated the prosthesis needed to expand an additional 10 cm.

The engineers considered the options for materials, choosing a smooth, low-wear cobalt-chrome surface for inside the elbow, where the implant would rub against Mark’s ulna, and porous surfaces in other spots where they wanted Mark’s soft tissues to knit themselves together with the implant.

They also took a hard look at the expansion mechanism for the prosthetic. In the past, they had made expandable thighbones that could be lengthened by inserting a screwdriver through a tiny incision in a patient’s bent knee, allowing the physician to turn a screw that ran parallel to the length of the upper leg. But the shoulder and elbow joints have a different geometry than the knee, and inserting a screwdriver end-on into a humerus implant would require invasive surgery. Instead, the team tested designs for a worm gear that would allow Rinsky to lengthen the prosthesis with a small cut in the side of Mark’s arm. (Worm gears shift the direction of rotation 90 degrees — so a screwdriver inserted and turned perpendicular to Mark’s bone could be used to extend a prosthesis running the length of his arm.)

“Because of the patient’s age, we wanted to give them a device that was as minimally traumatic as possible,” Smits says.

Leslie Williamson

Mark Blinder tells his parents, “I have a special arm.” His surgeon removed his right humerus, containing a rare bone cancer, and replaced it with an implant that expands as he grows — a treatment never before attempted in a toddler.

Mark Blinder tells his parents, “I have a special arm.” His surgeon removed his right humerus, containing a rare bone cancer, and replaced it with an implant that expands as he grows — a treatment never before attempted in a toddler.

The engineers went through several rounds of planning over a two-month period, sending Rinsky each iteration of the design. “They would show me something that I could not fit into the arm, and I would say, ‘I have to close the incision!’” he says. It was hard to design a small implant strong enough to extend to the size of an adult humerus, Smits explains. Eventually, the collaborators settled on an implant with less lengthening capability than Rinsky had hoped for — instead of extending 10 cm, the final implant will “grow” 4 cm with Mark, leaving his right arm a bit shorter than the left.

Fortunately for the time-crunched team, the new implant didn’t require FDA clearance because it was a custom device prescribed by a surgeon to meet Mark’s specific needs.

Even when the design was finalized, Rinsky wasn’t sure the prosthesis would fit inside Mark’s arm. He ordered a back-up metal rod to have on hand during surgery, just in case.

Early on Dec. 4, 2008, the surgical team wheeled Mark to the operating room. His parents watched him go with trepidation. Not wanting to scare the little boy, they hadn’t told him much about what to expect, but they were anxious. Ostrovskaya hadn’t slept the previous night.

Rinsky was concerned, too. Conditions weren’t ideal: He was hobbling around on a broken foot, the result of a fall at home. His team was adjusting to a new work environment, the new pediatric surgical suites at Packard Children’s, which had opened just three days before. And, because of Mark’s chemotherapy-weakened immune system, everyone on the team was encased in space-suit-like outfits to cut infection risk. The team members also had to talk more loudly than usual, to be heard over the whir of the fans inside the suits.

Then there were the technical challenges of the procedure. “The surgery involved taking out the entire bone without touching it,” Rinsky says. The bone had cancer cells on its surface, which could easily have spread to surrounding healthy tissue. “It was like carving out a peach pit without ever touching the pit, staying in the pulp.” He removed the bone along with a thin, protective layer of soft tissue and muscle, working carefully to preserve nearby nerves and blood vessels.

Once the cancerous bone was out, Rinsky implanted the artificial bone. It was daunting at first — Mark’s arm looked “like a banana peel with the banana removed,” Rinsky says. “There was a little tiny bit of muscle, enough to work, and then the main pipes and wires and the skin.”

The prosthesis had a piece of Dacron fabric at the top, which Rinsky sewed to soft tissue in Mark’s shoulder. At the elbow, he saved Mark’s ligaments and placed those around the prosthesis as best he could, snuggling the implant’s smooth end into the pocket next to the other bones in Mark’s elbow. Then he started sewing up Mark’s arm. Luckily, the incision closed. The surgery had taken about five hours.

“Dr. Rinsky came out of the operating room and said, ‘The prosthesis fit perfectly fine, he is doing great,’” remembers Blinder.

Soon, there was more good news: Mark’s tumor was confined to the bone that had been removed, and its malignant cells were dead, a sign that his chemotherapy had worked properly. He spent a month healing from surgery, then received more chemotherapy to reduce the chance the cancer would return. He’ll have three to four minor surgeries over the next several years, in which Rinsky will lengthen the implant. After obtaining more follow-up data, Rinsky and his colleagues plan to write about the case for the scientific record.

Once the cancerous bone was out, Rinsky implanted the artificial bone. It was daunting at first — Mark’s arm looked “like a banana peel with the banana removed,” Rinsky says. ”There was a little tiny bit of muscle, enough to work, and then the main pipes and wires and the skin.”

Mark’s parents knew he was truly feeling better when he began getting into mischief again. In June, just before his final round of chemotherapy, he was playing “strongman” and accidentally dropped a 2-pound dumbbell on his head. “It was pure 4-year-old,” says Rinsky with a grin. (A CT scan showed the bump had caused no harm.) “He is a very spunky kid,” says Marina.

At home in Palo Alto, Mark is gradually re-learning to use his right hand and arm. He had switched from being right- to left-handed after the surgery, but is now shifting some tasks back to his right hand. He’s moving his right wrist and fingers, can pick up small objects, and is receiving physiotherapy to rebuild strength and flexibility in his elbow and shoulder joints. Although Mark won’t ever regain full function in those joints, he’s using the arm more each day, Ostrovskaya says. He tells his parents, “I have a special arm.”

And he’s back to his active self. On a warm fall afternoon nearly a year after surgery, he chases big brother Tony enthusiastically around their neighborhood playground. The boys, now 4 and 8, kick a soccer ball back and forth with strong, practiced shots. The ball has helped strengthen Mark’s right arm, too. “Hands out!” Tony calls, standing ready to toss it to his little brother, who catches it with both arms outstretched.

Later, Mark holds his orange plastic baseball bat high above his head — again, with both arms — then jumps off a low platform on the climbing frame, shouting “Tarzan!” with a wild gleam in his eye. Seeing his interest in the bat, Ostrovskaya tries to coax him to play baseball, but, like most 4-year-olds, he’s much more pleased with his self-made entertainment than a grown-up game.

Again, he’s up on the climbing frame, bat aloft, poised to jump.

Mark leaps into the air.

“TAAAR…ZAAAN!!!”

E-mail Erin Digitale