Brownout

The mitochondria detective work gets a little easier

By Erin Digitale

Illustration by Shout

When she was 13 years old, Veronica Segura spent a month in a psychiatric hospital being treated for an eating disorder she didn’t have.

“It was one of the worst experiences of my life,” says Segura, now 25.

Although she was thin, Segura always tried to eat normally. When her middle-school classmates in Stockton, Calif., asked if she was anorexic, she felt bewildered. “I didn’t know what an eating disorder was until people started bringing it up,” she says. So she began wearing baggy clothes to deflect the awkward questions. Her mom, who had been a thin teenager, wasn’t worried, assuming Segura would gain weight with age. But then, after Segura became severely dehydrated and a short hospitalization corrected it only temporarily, she was officially diagnosed with anorexia.

During her stint in the Modesto psychiatric hospital, Segura sensed her diagnosis couldn’t be right. But she was surrounded by clinicians — authoritative adults — who were sure she was starving herself. “I started to believe it, too,” she says now. “I started to believe I was really anorexic.” She couldn’t put weight on, though she ate the hospital meals and the fast food that one of her three doting big brothers smuggled in a few times every week.

Eventually, Segura’s mystified doctors referred her to Lucile Packard Children’s Hospital, where she ended up in the care of Greg Enns, MB, ChB.

“Usually, by the time patients get to me, they’ve already been on a diagnostic odyssey,” says Enns, an associate professor of pediatrics at Packard Children’s. His patients, suffering symptoms that fit no recognizable constellation, have grown used to physicians’ shrugged shoulders and puzzled looks. Enns, a soft-spoken, thoughtful man partial to whimsical neckties, is their medical detective of last resort.

Enns’ specialty is mitochondrial disease, a group of rare disorders caused by breakdowns in the “power plants” inside our cells — the mitochondria. Normally, these tiny capsules full of worker proteins efficiently transform food molecules such as glucose into the energy that drives our every nerve impulse, heartbeat and muscle contraction. When gene mutations make these power plants malfunction, they can wreak havoc on nearly any part of the body.

For each case, it’s Enns’ job to sort through a confusing litany of symptoms and clinical findings, which could range from mild (droopy eyelids, low weight or generalized fatigue) to life-threatening (respiratory failure, neurological problems, seizures, strokelike episodes or organ failure), to determine the likelihood the patient has a mitochondrial defect.

“It’s a combination of problems that’s unusual, a pattern you might not expect, that gives a clinical clue to these disorders,” he says. For instance, most childhood neurological diseases involve only the nervous system, whereas mitochondrial patients with neurological deterioration may have other failing organs. “Trying to diagnose mitochondrial disease is like reading tea leaves.”

If Enns and other scientists could take the mystery out of mitochondrial disease, the implications would stretch far beyond ameliorating rare gene defects like the one that caused Segura’s confusing symptoms. Scientists suspect less-severe mitochondrial malfunctions lie at the root of such common disorders as diabetes, autism and cancer.

Fighting for breath

Enns first saw Segura after she was referred from the psychiatric hospital to the Comprehensive Eating Disorders Program at Packard Children’s. There, physicians noticed she was unusually weak, and saw mild elevation in her levels of creatine kinase, a non-specific blood marker for muscle disease. Suspecting a genetic or metabolic disorder, they called Enns. He quickly learned that two of Segura’s seven siblings, a brother and a sister, had died of what her family believed was a form of muscular dystrophy. Amazingly, the physicians in Modesto were so focused on Segura’s low weight that they didn’t take a family history, and her family never questioned the anorexia diagnosis.

“Her [deceased] sister’s muscle biopsy showed ragged red fibers,” or muscle fibers bloated with clusters of deformed mitochondria, Enns says. Not all mitochondrial disease patients have ragged red fibers, but when they do show up, they’re a telltale clue. “We thought, this sounds like mitochondrial disease.”

Enns then asked Packard pulmonologist Terry Robinson, MD, to evaluate Segura’s shallow breathing. “Her breathing tests demonstrated decreased lung volume,” Robinson says — more evidence for mitochondrial disease in this context. At last, after several months, Segura was free of her misdiagnosis. She felt vindicated, and relieved to have a diagnosis that, unlike anorexia, made sense to her. Though it’s still painful to think about the “bad days” in Modesto, “I’m more at peace with my situation now,” she says.

“Veronica is unusual in terms of her positive outlook and her determination to adapt over time,” says Robinson.

Even with the diagnosis, Enns and Robinson initially couldn’t pinpoint which gene mutation Segura suffered. And more than 10 years later, their only treatment options have limited efficacy. Now the mother of a 2-year-old, Segura takes a combination of high-dose vitamins and antioxidants and uses a non-invasive ventilator 22 to 23 hours a day to offset the weakening of her respiratory muscles. Her husband, Aurelio Fernandez, is the one who chases after their active girl, cares for their modest home in Stockton and pushes Segura’s wheelchair for any outing that requires more than a few steps. Segura has no idea how long she’ll live. “My main concern is my daughter,” she says. “What if I am gone in a month or two?”

Inside the factory

Mitochondrial disease is difficult to diagnose because the mitochondria themselves are such complex pieces of cellular machinery.

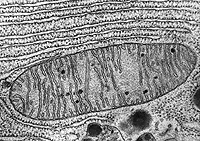

These microscopic energy factories, flexible oblongs 1 to 10 micrometers long, provide on-the-spot fuel for thousands of cellular activities. Electron micrographs that show cells’ insides reveal mitochondrial interiors filled with squiggly, protein-speckled membranes. The mitochondria can split, fuse, change shape and move around the cell to meet local energy needs. Cells that consume lots of energy — such as muscle — are loaded with more mitochondria than metabolically quiet cells.

Keith R. Porter/

Photo Researchers Inc.

A mitochondrion

A mitochondrion

The stripes inside are membranes where energy-transforming reactions take place.

Scientists think mitochondria originated from a symbiotic relationship between two kinds of primitive cells. Bigger cells engulfed smaller ones, the theory goes, and the small cells, ancestral mitochondria, took over a digestivelike function for the big cells, converting food molecules to useable packets of energy. The symbiosis theory is supported by the fact that modern mitochondria carry a bit of their own DNA, enough to code for 37 genes.

Ideally, mitochondrial worker proteins function like a well-managed assembly line. The factory consumes oxygen and sugar and produces carbon dioxide and adenosine triphosphate, a small energy-carrier molecule that fuels nearly every aspect of cell function.

The instructions for building the mitochondria are encoded in more than 1,200 genes, including the 37 genes on the mitochondrial DNA and hundreds more on DNA in the cell’s nucleus, half of which comes from each parent. There’s one gene per assembly-line cog. If the instructions are wrong, the line breaks down. This is how gene mutations cause mitochondrial disease.

Defective mitochondria may spew out toxic “free radical” molecules that damage cells’ DNA, proteins and membranes. Faulty genes can hobble cells’ ability to make new mitochondria, leaving the body with too few “power plants.” Or, mutations could derail the mitochondrial assembly line in subtle ways that manifest only under stressful circumstances, such as during infection.

A case in point

And so patients come to Enns with symptoms in almost any body part. Tissues hungry for energy, such as brain, heart, muscle, liver and kidney, take the hardest hit from mitochondrial failures, but any organ can be affected. New problems with the mitochondria can crop up at all stages of life. It’s enough to bewilder even the best diagnostic detectives.

Enns tackles the challenge with a battery of tests worthy of a forensics expert — or a modern mechanic.

“The mitochondria are like engines,” he says. “When a car engine doesn’t work right, it smokes.” Similarly, malfunctioning mitochondria produce nasty gunk Enns refers to as “biochemical smoke.” It’s the metaphor he uses to explain his detective work to patients’ parents on a typical day in the Packard neurogenetics clinic.

“Here’s Pooh — can you follow him?” he asks a grade-schooler in clinic, picking up his Winnie-the-Pooh necktie and moving it across her line of vision to see whether her eyes track normally. The girl, who suffers seizures and developmental delays, is in the clinic with her parents for a complete evaluation by Enns’ team. He flexes her arm at the elbow, making windshield-wiper noises (“shoo, shoo”) while he checks her muscle strength. When his neurologist colleague Ching Wang, MD, PhD, taps the triangular head of a reflex hammer below the girl’s kneecap, Enns elicits a giggle by explaining jokingly, “We take out our hammers and we smash you, that’s our job.”

To obtain more clues about the nature of the patient’s suspected mitochondrial disease, Enns and resident physician Eric Muller, MD, ask her parents about her physical complaints, behavior and whether any other family members have shown signs of mitochondrial disease. A muscle biopsy performed a few years ago has already given hints about the appearance, number and function of the patient’s mitochondria. Now Enns asks Muller to order a complete blood count, a blood chemistry panel and gene sequencing to hunt for traces of biochemical smoke and evidence for or against particular gene defects. Muller also writes referrals to specialists who can evaluate specific organs systems, including a cardiologist, an endocrinologist and an ophthalmologist.

Erin Digitale

Mystery solved

Mystery solved

Veronica Segura and her husband, Aurelio Fernandez, finally know what the trouble is.

Ideally, the puzzle pieces gleaned by Enns and his colleagues will point toward a well-recognized flavor of mitochondrial disease, and they can confirm their diagnostic hunches with a genetic test that pinpoints a specific mutation. More often, however, the team can only speculate that the patient has a defective mitochondrial gene for which no test exists.

“It’s like taking a car to the garage and having the mechanic say only that something is wrong with the engine,” Enns says. “That doesn’t help a lot. Sure, you know it’s not the wheels or the axle, but what exactly is the defect?”

Being unable to identify the mutated gene produces extra worries for patients and their families, especially if they’re concerned about disease risk for a patient’s siblings or children. When Veronica Segura became pregnant, for instance, she had no way of knowing whether her baby would inherit her illness.

Unfortunately, even when doctors pin down the identity of a mutation, treatment for mitochondrial disease is mostly palliative. Segura’s ventilator fits this category: It helps her breathe, but won’t cure her weak respiratory muscles. The antioxidant cocktail she takes is an attempt to tackle bad mitochondria head-on — physicians hope it combats the destructive effects of the free-radical “smoke.” But it’s never been clinically tested, and doctors give the mixture without an effective way to monitor its actions. “I’m frustrated by the whole approach of, ‘Take these meds, how do you feel?’” says Enns, one of a small cadre of researchers worldwide focusing on mitochondrial diseases. “It’s not a good way to do medicine.”

Looking for a sign

To combat his frustration, Enns began looking for a biomarker — a measurable indicator from patients’ bodies — that could quantify their disease severity and responses to treatment. A discovery he and colleagues made in his lab offers some hope. They studied the white blood cells of 20 mitochondrial disease patients and found lower-than-normal levels of the body’s most prevalent naturally occurring anti-oxidant, glutathione.

The study, published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences in February, is the first to identify a robust biomarker of mitochondrial disease status that could be used as a diagnostic tool. Even more exciting, new research shows that patients taking the antioxidant cocktail had normal glutathione levels — suggesting that the cocktail really does help combat the disease.

Mitochondrial disease researcher William Craigen, MD, PhD, the director of the metabolic clinic at Texas Children’s Hospital, calls Enns’ work “the beginning of insight into the mechanisms of mitochondrial disease.” Craigen, who was not involved in Enns’ study, is encouraged by the possibility of making a long-term difference in patients’ health with “a simple, easy-to-administer treatment,” he says.

The researchers dedicated to mitochondrial disease number only in the dozens worldwide. Meanwhile, because gene sequencing has become easier, the volume of data on genes that affect mitochondria has gone from a trickle to a tsunami. The genes are garnering attention from researchers across the disease spectrum — but the information has been hopelessly disorganized.

So Enns’ colleague Curt Scharfe, MD, PhD, a research associate at Stanford’s Genome Technology Center, is leading a computing project to help researchers navigate the confusing thicket. Scharfe’s team developed Mitophenome.org, a searchable, open-source database indexing more than 1,600 research papers that describe 502 clinical features and symptoms associated with defects in 174 genes that affect mitochondrial function. Scientists can search the database by any symptom for a list of associated gene defects, or search by gene for a list of reported symptoms.

It’s a medical detective’s gold mine.

Says Scharfe, “Once we understand the correlations between gene defects and disease, then we can start thinking about treatment.”

For now, much of the detail of mitochondrial disease remains shrouded in mystery.

But sometimes, for a single patient, a glimmer of hope breaks through the fog. Veronica Segura recently learned what’s at the root of her disease: a mutation in the cellular instructions for building the enzyme thymidine kinase 2, which plays a key role in synthesizing new mitochondrial DNA. Most important for Segura, a child must receive a bad copy of the gene from each parent to manifest disease. Segura’s husband, Aurelio, doesn’t carry the disease gene, which means their little daughter will never suffer her mother’s mitochondrial illness.

“That was a huge relief,” Segura says. Recalling the agony of being a young teen stuck in a psychiatric hospital, her family and doctors convinced by her faulty diagnosis, she adds, “I’m so happy and thankful that my daughter doesn’t have to go through what I’ve been through.”

Erin Digitale is at