Excerpts from a Vietnamese doctor's wartime diaries

Courtesy of Tram family |

|

|

|

|

As soon as they came to light in 2005, the diaries of a young doctor who worked for North Vietnam in the Vietnam War became a media sensation in her homeland. Dang Thuy Tram died in the war, but she springs to life from the journal chronicling her days as a physician on the front lines.

The diaries are a Vietnamese best seller and a cultural phenomenon — appearing as excerpts in newspapers and inspiring a documentary film. A hospital and library in Vietnam have been named in Tram’s honor. Harmony Books plans to publish an English translation in September.

![]() INTERVIEW: Paul Costello talks to Frederic Whitehurst about finding Dang Thuy Tram's diary—and its impact. (23 minutes).

INTERVIEW: Paul Costello talks to Frederic Whitehurst about finding Dang Thuy Tram's diary—and its impact. (23 minutes).

![]() INTERVIEW: School of Medicine’s Paul Costello talks to Robert Whitehurst about his search for Tram’s family (22 minutes).

INTERVIEW: School of Medicine’s Paul Costello talks to Robert Whitehurst about his search for Tram’s family (22 minutes).

Tram’s diaries begin in April 1968 when she’s 25 and several months into her first post-medical school job, chief physician at a field hospital in central Vietnam. The Tet Offensive is raging; though her hospital is a civilian clinic, she treats mainly soldiers. Sometimes she walks for miles through the rugged terrain to care for wounded fighters. Her duties also include training new health practitioners. The last entry is June 20, 1970, two days before she is killed by U.S. soldiers.

Frederic Whitehurst, whose task was to sort through captured documents for U.S. military intelligence, found the diaries. In Vietnam in 1970, he was throwing documents into a fire in a 55-gallon drum when his interpreter, who was watching, said, “Don’t burn this one, Fred. It has fire in it already.” He saved the small diary and later saved a second. In 1972 he took both diaries home, after serving three tours in Vietnam.

Whitehurst says he often thought about returning the diaries to Tram’s family, but tracking them down eluded him. In the years after the war, he had joined the FBI, making contact with an enemy nation problematic. Eventually, U.S.-Vietnam relations normalized, and Whitehurst left the FBI. But the war had left psychological scars that flared when he revisited the diaries. So Whitehurst's brother, Robert Whitehurst, picked up the ball, arranging for them to take the diaries to a conference on the Vietnam War at Texas Tech University in March 2005. An Air Force veteran they met agreed to take copies of the diaries with him when he went to Hanoi the following month. With help from a Quaker group there, he found Tram's family, discovering that her mother and three sisters were all alive, though her father and brother had died.

|

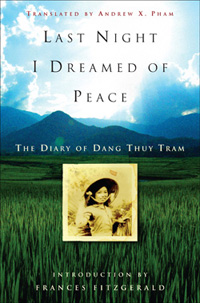

The forthcoming Harmony Books edition, Last Night I Dreamed of Peace, is a translation of the diaries into English by Andrew X. Pham, with an introduction by the acclaimed Vietnam War journalist Frances FitzGerald. The following excerpts are published with permission.

20 May 1968

We say farewell to our patients today. They have recovered enough to return to their combat units. Instead of being joyful and happy, we are all sad, both physicians and patients. After over a month at the clinic, they have become like friends and family. It’s wrenching to see them leave. ...

31 May 1968

Today we had a major base evacuation to evade the enemy’s mopping-up sweeps operation. The whole clinic was moved, an infinitely exhausting undertaking. It’s heart-wrenching to see the wounded patients with beads of sweat running on their pale faces, struggling to walk step by step across narrow passes and up steep slopes. If someday we find ourselves living in the fragrant flowers of socialism, we should remember this scene forever, remember the sacrifice of the people who shed blood for the common cause. …

4 June 1968

… Rain falls without respite. Rain deepens my sadness, its chill making me yearn for the warmth of a family reunion. If only I had wings to fly back to our beautiful house on Lo Duc Street, to eat with Dad, Mom, and my siblings, one simple meal with watercress and one night’s sleep under the old cotton blanket. Last night I dreamed that Peace was established, I came back and saw everybody. Oh, the dream of Peace and Independence has burned in the hearts of thirty million people for so long. For Peace and Independence, we have sacrificed everything. …

Courtesy of Tram family |

|

|

|

|

20 July 1968

The days are hectic with so much work piling up, critical injuries, lack of staff personnel; everybody in the clinic works very hard. My responsibilities are heavier than ever; each day I work from dawn till late at night. The volume of work is huge, but there are not enough people. I alone am responsible for managing the clinic, treating the injured, teaching the class. More than ever, I feel I am giving all my strength and skills to the revolution. The wounded soldier whose eyes I thought could not be saved is now recovering. The soldier whose arm was severely inflamed has healed. Many broken arms have also healed. …

25 July 1968

I came to sit by Lam’s bedside today. A mortar had severed the nerves in his spine, the shrapnel killing half of his body. Lam was totally paralyzed. His body was ulcerated from the chest down. He was in excruciating pain.

Lam is twenty-four this year, an excellent nurse from Pho Van. Less than a month ago, he was assigned as supplement to the District Civil Medical Department. The enemy came upon Lam while he was on the road during his recent assignment; Lam tried to get into a secret shelter, but the Americans were already upon him when he opened the cover; the small shrapnel painfully destroyed his life. Lam lay there waiting for death. In the North, a severed spinal cord is already a hopeless case, let alone here. Lam knows the severity of his injury and is deep in misery and depression. …

Oh! War! How I hate it, and I hate the belligerent American devils. Why do they enjoy massacring kind, simple folks like us? Why do they heartlessly kill life-loving young men like Lam, like Ly, like Hung and the thousand others, who are only defending their motherland with so many dreams?

29 July 1969

The war is extremely cruel. This morning, they bring me a wounded soldier. A phosphorus bomb has burned his entire body. An hour after being hit, he is still burning, smoke rising from his body. This is Khanh, a twenty-year-old man, the son of a sister cadre in the hamlet where I’m staying. An unfortunate accident caused the bomb to explode and severely burned the man. Nobody recognizes him as the cheerful, handsome man he once was. Today his smiling, joyful black eyes have been reduced to two little holes — the yellowish eyelids are cooked. The reeking burn of phosphorus smoke still rises from his body. He looks as if he has been roasted in an oven.

Courtesy of Tram family |

|

|

|

|

I stand frozen before this heartbreaking tableau.

His mother weeps. Her trembling hands touch her son’s body; pieces of his skin fall off, curled up like crumbling sheets of rice cracker. His younger and older sisters are attending him, their eyes full of tears.

A girl sits by his side, her gentle eyes glassy with worry. Clumps of hair wet with sweat cling to her cheeks, reddened by exhaustion and sorrow. Tu (that’s her name) is Khanh’s lover.

She carried Khanh here. Hearing that he needed serum for a transfusion, Tu crossed the river to buy it. The river was rising, and Tu didn’t know how to swim, but she braved the crossing. Love gave her strength.

The pain is imprinted on the innocent forehead of that beautiful girl. Looking at her, I want to write a poem about the crimes of war, the crimes that have strangled to death millions of pure and bright loves, strangled to death the happiness of millions of people, but I cannot write it.

My pen cannot describe it all, even though this is one case I feel with all my senses and emotions.

5 August 1969

I’m on a night emergency-aid mission, going through many dangerous parts of the national highway on which enemy vehicles frequently commute, and passing through the hills filled with American posts. Lights from the bases shine brightly; I go through the middle of the fields of Pho Thuan. Bright lights shine from three directions around me: Chop Mountain, Cactus Mountain, and the flares hanging in midair in front of me. The light sources cast my shadows in different directions, and I feel like an actor on stage, as in the days when I was still a medical student performing in a choir. Now I am also an actor on the stage of life; I am taking the role of a girl in the liberated area, wearing black pajamas, who night after night, follows the guerrillas to work between our areas and those of the enemy.

Perhaps I will meet the enemy, and perhaps I will fall, but I hold my medical bag firmly regardless, and people will feel sorry for this girl who was sacrificed for the revolution when she was still young and full of verdant dreams.

20 June 1970

Suddenly I recall a line from a poem:

Now immense sea and sky

Oh, uncle, do you understand this child’s heart…

No, I am no longer a child. I have grown up. I have passed trials of peril, but somehow, at this moment, I yearn deeply for Mom’s caring hand. Even the hand of a dear one or that of an acquaintance would be enough.

Come to me, squeeze my hand, know my loneliness, and give me the love, the strength to prevail on the perilous road before me.

Reprinted from LAST NIGHT I DREAMED OF PEACE: THE DIARY OF DANG THUY TRAM. Translation copyright 2007 by Andrew X. Pham. To be published in September 2007 by Harmony Books, a division of Random House Inc.

Comments? Contact Stanford Medicine at