Why test a pill that can kill, if the patient is not that ill?

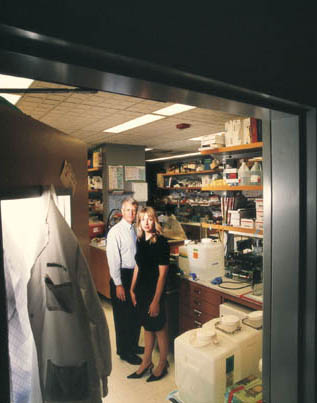

Ethan Hill |

|

|

|

By MITZI BAKER

Neurologist Annette Langer-Gould, MD, has never been more agitated by a patient’s case. Seven years ago, a man in his 30s came to her with worsening multiple sclerosis.

In 2002, Langer-Gould referred him to a clinical trial of a new multiple sclerosis treatment. As a great believer in science, her patient was very willing to experiment, despite the possibility that his symptoms might abate on their own, she says.

Unfortunately, the experiment went awry. As a result of the drug being tested, he developed a rare viral infection, progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy, or PML.

The virus causes mental deterioration; inability to see, speak or coordinate movements; and ultimately, paralysis, coma and frequently death — often in a matter of months.

The drug that crippled Langer-Gould’s patient is natalizumab, which has the brand name of Tysabri. In November 2004, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration fast-tracked its approval following promising early trial results: The risk of relapse dropped from an average of two relapses every three years using other approved drugs to one every three years with Tysabri.

But within months, three of the 3,000 patients taking the drug, including Langer-Gould’s patient, had developed PML, and two of them died — one of whom had been misdiagnosed with multiple sclerosis in the first place. The FDA withdrew Tysabri just three months later.

Profoundly affected by her experience with this patient, Langer-Gould, a Stanford clinical instructor, now advocates testing new drugs only on people who have exhausted their other treatment options and who have indications that their disease is progressing.

So in March, when an FDA advisory committee recommended that the drug be returned to the market, she took action. She approached multiple sclerosis specialist Lawrence Steinman, MD, a Stanford neurology professor, about writing an article arguing that if a drug has a known risk of death, it should be given only to those patients who are likely to suffer severe disability from their disease. That is almost the reverse of what happened in the Tysabri trials, which excluded the most severely affected patients.

Their article appeared in the March 4 issue of The Lancet. “Some people are opposed to what we wrote, but we didn’t say anything that epidemiologists haven’t been saying for 20 years,” says Langer-Gould. “The bigger problem is that we can’t accurately determine if people have the disease.” Their article highlights that multiple sclerosis is hard to diagnose, and its course, difficult to predict.

Her biggest concern is that some patients who want to take drugs such as Tysabri might be acting on unrealistic fears about their prognosis and are poorly informed about the drug’s dangers.

Though her PML patient is alive and has made marked improvements after a year, at his worst he was unable to move or interact at all.“My experience with this definitely makes me more cautious about prescribing a drug with such a risk,” Langer-Gould says.

Comments? Contact Stanford Medicine at