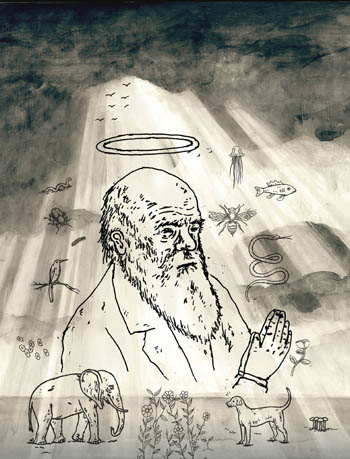

Scientists battle the forces of intelligent design

Jonathon Rosen |

|

|

|

By MARK SHWARTZ

Like most scientists, Greg Clark prefers the lab to the limelight. An associate professor of bioengineering at the University of Utah, he’d rather hone new designs for prosthetic limbs than engage in public debates about religion and science. But last year, his comfortable academic bubble suddenly burst when a Utah politician proposed that a religious concept called intelligent design be taught in state public schools alongside Darwin’s theory of evolution.

“Before then, evolution was a non-issue in Utah,” Clark recalls. “But this was an attack on science itself. As a scientist, educator and the father of a middle-schooler, I felt a moral obligation to speak out.”

Clark was all too familiar with the war on evolution. Public schools in Kansas and Pennsylvania were already embroiled in highly publicized anti-evolution campaigns led by advocates of intelligent design (known as I.D.), who claim that living things are so complex, they must have been purposefully designed by a supernatural intelligence. I.D. backers reject the fundamental tenets of evolutionary theory — namely, that species evolve over time through natural selection and random genetic mutations.

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||

Since 2001, the teaching of evolution has been challenged in more than 40 states, from Pennsylvania to California. In many places, including Utah, the anti-evolution movement has been led by religious ideologues who consider Darwin’s theory antithetical to the biblical version of creation. At the same time, they tout intelligent design as a legitimate scientific theory, not a theological concept.

“On a moral level, I found that most disturbing, because the real motivation behind I.D. is religious, not scientific,” Clark says. With the integrity of science education in Utah in jeopardy, he decided it was time to go public — a commitment that would propel this quiet, deliberate scientist to testify before the state board of education and a Utah Senate committee. In February, the efforts of Clark and other concerned Utah scientists helped carry the day when the state House of Representatives overwhelmingly rejected an anti-evolution education bill.

Getting religion

From coast to coast, scientists who once paid little attention to the politics of intelligent design have begun making their voices heard.

“You could say that scientists are finally getting religion,” quips Eugenie Scott, PhD, executive director of the Oakland-based National Center for Science Education, the leading pro-evolution advocacy group in the United States. In recent months, her office has been contacted by researchers and educators from many fields who now see the I.D. movement as part of a broader political attack on American science — from the Terry Schiavo “right-to-life” controversy to federal restrictions on stem cell research to the Bush administration’s attempted silencing of climate change experts.

“I think scientists are pretty nervous about the way scientific data are being shaped to suit administration policy,” Scott says. “Science needs to stand alone and not be modified to suit ideology.”

Medical researchers and clinicians should be particularly concerned about the politicization of science, argues Irv Wainer, PhD, a clinical oncology researcher with the National Institutes of Health. “People are afraid that teaching evolution will take away their kids’ faith in God, and that they will end up in hell,” he says. “What they don’t understand is that all of the work I do on multidrug resistance in breast cancer is based on evolutionary theory.”

Troubled by the growing strength of the I.D. movement, this February Wainer formed the Alliance for Science, a national coalition of scientists, educators and clergy whose mission is to improve the public’s understanding of evolutionary theory and to clarify the differences between theology and science.

Project members plan to commemorate Darwin’s 198th birthday next February by holding a “national evolution sabbath” during which religious leaders will turn over their Sunday sermons to scientists, who will discuss evolution and faith.

Some scientists outside of biology are just as concerned about the I.D. movement. “In the past, I had always brushed it off as inconsequential and no danger,” says Herb Kroemer, PhD, professor of electrical and computer engineering at the University of California-Santa Barbara and recipient of the 2000 Nobel Prize in Physics. “But within the last year, I realized I had to get involved. And people with certain recognition, such as myself with a Nobel Prize, have a double responsibility.”

In January, Kroemer wrote a pro-evolution editorial, warning that religiously motivated attacks on science “threaten the continued prosperity and security of our nation in a world where we increasingly have to compete with other nations that have developed strong science-based technologies in areas that were once unchallenged domains of the United States.”

Jonathon Rosen |

|

|

|

Un-holy alliance

The term “intelligent design” was virtually unknown until the 1990s. That’s when the Discovery Institute, a well-funded conservative think tank in Seattle whose supporters include wealthy, ultraconservative Christians, launched a national anti-evolution campaign. On its board sits the billionaire heir to the Home Savings & Loan fortune, Howard Ahmanson Jr. — one of the 25 most influential U.S. evangelicals, according to a 2005 Time magazine article.

In a 1998 internal memo known as the Wedge Document, institute leaders laid out a five-year strategic plan to take the I.D. gospel to the media, church leaders and sympathetic politicians across America. But the attack on evolution was only the beginning. According to the Wedge Document, the goal is to overthrow the culture of "materialism" — the belief that biology, chemistry and enviornment dictate human behavior and thoughts — which “has infected virtually every area of our culture.”

So far, the I.D. movement has been particularly adept at reaching out to the conservative wing of the Republican Party, winning the support of President George W. Bush; Senate Majority Leader Bill Frist, MD; Sen. John McCain; and other party leaders.

“I think it’s horrible that the president supports the claim that intelligent design is an alternative scientific theory that should be discussed alongside evolution,” says Kroemer. “Anti-evolution is really anti-scientific, which makes it inherently anti-education. It’s really the dumbing down of the American people.”

Jon Miller, PhD, director of Northwestern University’s Center for Biomedical Communications, says support for intelligent design is part of an overall Republican strategy to hold onto the party’s solid evangelical Christian base.

“There is no other country where a political party has attempted to make evolution a political issue,” Miller says, noting that anti-evolutionary language has even been added to several state Republican Party platforms.

The Republican strategy appears to have broad appeal. In a Gallup Poll conducted in March, for example, 57 percent of Americans agreed with the statement, “God created man exactly how the Bible describes it.” Another 31 percent said they believed in “God-guided” evolution, and 12 percent supported evolution in which “God had no part.” Other polls show that a majority of Americans favor teaching biblical creationism alongside evolution in science classes.

Theory vs. theology

“As scientists, we try to understand the world and arrive at practical truths,” says Matthew Scott, PhD, professor of developmental biology and of genetics at Stanford. “To do that, we conduct experiments. Religious beliefs, like intelligent design, are not experimentally testable or scientifically provable. You either believe in them or not. Indeed, it is often offensive to people to try to scientifically ‘test’ their religion.”

Instead of testing hypotheses with objective data and submitting the results for peer review, I.D. “researchers” take the political route, forming alliances with conservative politicians in order to force their untestable ideology into public school curricula under the guise of academic fairness and freedom of expression — a tactic that has become known as the “teach-the-controversy” strategy.

“There is no controversy when it comes to basic evolutionary theory,” counters Stephen Palumbi, PhD, professor of biological sciences at Stanford. “What they’re doing is part of a political agenda to change the definition of science and let people believe what they want to believe — or worse, what they’re told to believe — despite the facts.”

Not just a theory

Another tactic adopted by anti-evolutionists is the just-a-theory strategy, which cleverly uses the lay definition of “theory” to denigrate evolution. To most people, a “theory” is the same as a “guess” or a “hunch.” But in science, a theory is a testable hypothesis that’s been given special status because it’s backed by mounds of objective evidence. The theory of gravity is one example, evolution is another.

“There is overpowering evidence for evolution,” says Matthew Scott. “There’s absolutely no question about it in any serious biologist’s mind. Evolution remains the unifying principle of modern biology. We can observe evolution happening now, we can trace an ever-clearer fossil record, and there is vast knowledge of the molecular mechanisms that make gradual change in animal and plant forms possible. Of course there is still more to learn. Intelligent design, on the other hand, is essentially magic.”

If the United States wants to maintain its leadership role in biomedicine, then American students must be given a solid foundation in evolutionary biology, he argues. “We use evolutionary principles in the lab every day. Medical advances depend on understanding how cells and tissues and organs work, a goal that requires investigating molecular machines that have been evolving for hundreds of millions of years. The way things work in one organism often is how they work in others, with variations that are easy to understand and incorporate into our thinking. We share a lot of genetic hardware with other animals, but fine variations in how it is used — in essence the software — give rise to the differences among animals.”

A good example is the lab mouse — arguably the most important animal model in biology. Using evolutionary principles, molecular geneticists have determined that mice and humans descended from a common ancestor about 75 million years ago — not very long compared with the 3.8-billion-year history of life on Earth. Because of this close relationship, mouse and human DNA carry virtually the same set of genes, which explains why experiments conducted on lab mice provide such valuable insights into human disease and embryonic development.

“Much of the genetic machinery that builds the embryo is ancient,” Scott adds. “In our lab, we study genes that have been evolutionarily conserved between flies and mice and humans — over half a billion years — to learn how the embryo is constructed and how body-organizing genetic programs arose, function and change. Damage to these genes causes birth defects, cancer and neurodegenerative disease, and we are learning how to help humans by exploring how the genes work in other organisms.”

In addition to biology, evolution is considered a cornerstone of anthropology, paleontology, psychology and many other academic fields. Several multibillion-dollar industries also rely on Darwinian theory in developing new products — from genetically engineered drugs to pest-resistant plants to forensic DNA tests. Geologists have even developed a technique for finding remote oil deposits using evidence from the microfossil record.

“Why do we bother to teach evolution?” Palumbi asks. “Because it’s critical for people to know that we live in an evolving world, and that humans are the greatest evolutionary force on the planet.”

As an example, Palumbi points to the 60-year effort by medical scientists to control infections caused by Staphylococcus aureus bacteria. In the 1940s, penicillin was widely used to prevent staph infections. But within a few years, penicillin-resistant strains of the bacteria evolved, forcing researchers to find another drug, methicillin. By the mid-1980s, methicillin-resistant bacterial strains rose in prevelance so that the drug, vancomycin, had to be used as a last resort, adding billions a year to the nation’s health tab. Keeping a lid on this evolutionary escalation requires a thorough understanding of Darwinian evolution, Palumbi adds.

Evolution also explains why a painful, life-shortening disease such as sickle cell anemia persists — and why its incidence is decreasing in the United States. The sickle cell gene is prevalent among people living in Africa, India, the Mediterranean and Middle East. While carrying a pair of the genes leads to sickle cell anemia, just one gene per cell provides resistance to malaria, which is endemic in these regions. Because a single gene can be beneficial, it persists from generation to generation. In the United States, people with ancestry from these areas also carry the gene, but its frequency is dwindling. That’s because malaria is rare here, so inheriting the gene is disadvantageous.

Faith and science

Is it possible to bridge the divide between intelligent design and evolutionary theory? “I believe that individuals who have a deep faith can also respect the value of science, including what is known and unknown,” says Philip Pizzo, MD, dean of the Stanford School of Medicine. “However, when faith denies scientific data, a serious risk emerges which, in my opinion, extends beyond evolution or creationism, since it moves closer to theocracy and moral judgments that can challenge tolerance, open-mindedness and free thinking — and freedom itself.”

Unlike Pizzo, many doctors and medical researchers have remained silent on the evolution controversy. The American Medical Association, for example, has taken no position on the intelligent design movement, even though virtually every other science organization in the United States has issued a statement of concern. And last October, when the New England Journal of Medicine published an anti-I.D. perspective, the feedback was overwhelmingly negative.

“We got more letters about that piece than about any other article we published in recent years,” says journal deputy editor Robert S. Schwartz, MD, author of the controversial editorial. “Almost all of the letters were signed by people with ‘MD’ after their names. About two-thirds opposed me, many of them personally, calling me the anti-Christ and so forth.”

In his article, Schwartz called I.D. a pseudoscience and “an insidious menace to medicine” that could have “far-reaching consequences for the development of future generations of physicians… .” He called on leaders of professional medical societies and academicians to break their silence, and urged pro-science doctors to become more active in local politics.

“I didn’t expect that the article would provoke the volume of hate mail it did from throughout the country,” Schwartz says. Ultimately, the journal editors decided not to publish any of the reader responses.

There will always be a fault line between faith and science, adds Harvard University biologist E. O. Wilson, PhD. “But then I say, Let’s put that aside,” Wilson told National Geographic magazine in May. “Let’s recognize that science and religion are the two most powerful forces in the world, and see if instead of arguing about where life came from, we can devote ourselves to saving it — saving the creation.”

Dover decision

Those who have spoken up on behalf of scientific integrity can take heart knowing that, despite all of the rhetoric from the Discovery Institute, intelligent design often withers when confronted with a serious political or legal challenge. In December, the I.D. movement sustained its biggest setback when U.S. District Court Judge John E. Jones III in Philadelphia issued a devastating ruling against the Dover, Pa., school board, whose fundamentalist majority had voted to include intelligent design in K-12 science classes. The ruling was based on a lawsuit filed by 11 Dover parents, who argued that teaching I.D. violates the constitutional doctrine of separation of church and state.

Judge Jones agreed, noting that intelligent design has “utterly no place in the science curriculum.” Citing the Discovery Institute’s Wedge Document, the judge concluded that the “goal of the I.D. movement is not to encourage critical thought but to foment a revolution that would supplant evolutionary theory with I.D.”

In his ruling, the judge held the Dover school district liable for legal fees and expenses, and a few weeks later, a newly elected, pro-evolution school board reimbursed the plaintiffs’ attorneys $1 million.

“As a legal strategy, intelligent design is dead,” says Eugenie Scott of the pro-evolution National Center for Science Education. “The Dover decision is so complete, and the $1 million payment is so large, that other school districts will be reluctant to argue I.D. in court. But it remains very popular, and of course it will evolve.”

Future battles

Researchers and academicians continue to express concern about future attacks on science and science education. At this year’s annual meeting of the American Association for the Advancement of Science in St. Louis, speakers urged colleagues to reach out to the public, school boards and legislators whenever science is threatened by religious zealotry.

“Right now, the bad guys have better advertising, and the scientists are failing,” said conference speaker Philip Plait, PhD, an astronomer-educator at Sonoma State University. “You’ve heard them complain about activist judges. Be an activist scientist. Let them complain about that.”

Retired New Mexico physicist Marshall Berman may be the ideal role model for activist scientists everywhere. When fundamentalist members of the New Mexico State Board of Education proposed deleting all references to evolution and the age of the Earth from the state science curriculum, Berman, then a manager at the Sandia National Laboratories, decided to challenge an incumbent and ultimately defeated her in a statewide election. During his term from 1999 to 2003, Berman helped convince fellow board members to adopt new standards grounded in solid science.

But the anti-evolution forces have not surrendered, he warns: “These people are dedicated and determined. They’re absolutely convinced they are doing God’s work, and they’ll never stop. After 10 years of fighting them, I’m still scared to death.”

While the I.D. battle continues, the religious right may be taking aim at other sciences, including astrobiology — an emerging field that seeks to explain the biochemical origins of life in the universe — and neuroscience, which offers physiological rather than spiritual explanations for the human mind.

No matter what the future target may be — neuroscience, global warming or even the big bang theory — Berman argues that now is not the time for defenders of science to remain silent.

“We are in a battle for our U.S. Constitution and the very nature of our society,” he says. “It’s hard for me to imagine a bigger threat that all of us face. It’s time to take action. Get involved in politics and take a stand for science.”

| [an error occurred while processing this directive] |