They've made it to adulthood, but they're not home free

By LOUIS BERGERON

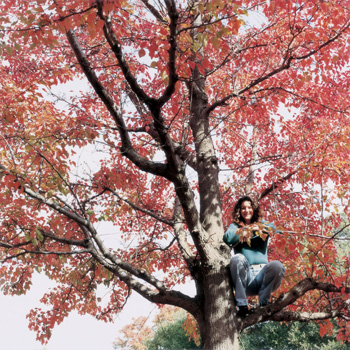

Nancy Magee was 13 when she was diagnosed with a cancerous tumor on one of her lungs — stage-4 Hodgkin’s disease. “As far as I know, the next stage is six feet under,” she says with characteristic candor, her way of explaining that there is no stage 5.

Fortunately for Magee, now 40, treatments combining chemotherapy and radiation — developed not long before her diagnosis — overcame her cancer.

Misty Keasler |

|

|

|

|

Medical advances in treating other serious childhood diseases, such as leukemia and lymphoma, cystic fibrosis, brain tumors and congenital heart problems, have enabled tens of thousands of kids to survive diseases that once would have killed them before adulthood.

But survival can come at a price, says Magee’s oncologist, Michael Link, MD, the Lydia J. Lee Professor of Pediatrics. Citing a recent report from the Institute of Medicine of the National Academies, Link says that one in 640 adults ages 20 to 39 has a history of childhood cancer. By 2010, it’s expected to be one in 450 young adults.

“There are two sides to that message,” says Link. “One is, we obviously are curing a lot of people — that’s great. But the downside is that patients are left with some real medical problems of varying severity,” says Link, who directs the center for cancer and blood disease at Lucile Packard Children’s Hospital.

Those medical problems, some obvious and some not, present a host of challenges not only for the patients, their families and their doctors, but also far beyond, rippling through our entire health-care system. How treatment is provided, to whom and who pays for it are all crucial issues.

And then there is the very nature of being cured. It sounds so final, as though it’s all over and done with, the shackles of disease shattered, the patient liberated. But even as treatment vanquishes the original illness, it raises the lingering specter of secondary diseases triggered by the treatment.

For Magee, treatment left her minus a spleen — removed to help assess the extent of her cancer — and with radiation-weakened bones. A daily low dose of penicillin helps compensate for her absent spleen, calcium supplements fortify her bones and time has healed her disappointment at being denied karate lessons as a teen because of her fragile frame. The medications and regular visits to her oncologist got her through the next 20 years in pretty good shape.

Then, in March 2001, her annual mammogram revealed a scattering of tiny specks in her left breast — prompting a biopsy. If it came back positive, Magee’s options were limited. She’d already had as much radiation as her doctors dared give her and more chemotherapy wasn’t an option she relished.

“That stuff made me sicker than a dog,” she says. “That almost killed me.” Her weight had dropped from 100 pounds until only 64 pounds remained on her 5-foot-2-inch frame. Her doctors were so concerned, they stopped her chemotherapy before she received the full course. “I was a walking toothpick,” she recalls.

“The idea of having to go through that again was just heart wrenching,” says Magee, now lab manager for Stanford’s Microbiology and Immunology Department. “And the other aspect was having to have my son see me go through this.”

Magee’s son, then 10 years old, had seen a cousin lose all her hair, eyebrows and eyelashes during chemotherapy, and had a tough time dealing with it.

Fortunately for Magee, though the specks were malignant, the cancer was spotted at stage 0 and hadn’t spread to her lymph nodes. Chemotherapy wasn’t necessary, but without that or radiation, a mastectomy was. Knowing she had a high risk of cancer in her other breast, she opted for a double.

Breast cancer is not uncommon in women who, like Magee, received radiation when they were girls, according to Link. Doctors now avoid radiating breast tissue as much as they can, but it’s a difficult call to make. “We can’t reduce the therapy to the extent that we’re not curing patients. That would be a tragedy,” he says.

Support groups help some women deal with cancer, and after her diagnosis Magee was urged to join one. “I’m going, why do I want to sit around a bunch of women bitching that they’re gonna lose their boobs? Hey, I don’t care, you know?”

As it turned out, Magee practically ended up running her own group, sharing her experience with five other women she knew who were diagnosed with breast cancer that year.

Magee credits her self-sufficiency in dealing with breast cancer in part to having already had one bout with cancer. Her sense of humor might have helped, too. Once, before her surgery, she bumped into her surgeon’s nurse in the hall. Looking serious, Magee asked her if the doctor did any radical surgery. When the nurse asked what she meant, Magee said, “Well, I was thinking maybe he could just cut my head off and turn it around because my shoulder blades stick out farther than my boobs do now. Then I won’t have to have implants.”

“Nancy’s a great example of a person who’s well-adjusted,” says Neyssa Marina, MD, professor of pediatrics, who runs a cancer survivors clinic at Packard Children’s Hospital. “She’s accepted that there are risks that happen because she got Hodgkin’s, and she talks about them. But there are other people who don’t quite get there.”

Getting young survivors to focus on their health can be tough, according to Marina. Some have a sense of entitlement, feeling that because they missed out on some of the fun of growing up, they should be excused from any further health problems. Others are so traumatized they just want to forget it all.

Marina tries to educate survivors about potential health problems so they’ll know the warning signs. But, she says, “They’re not always in tune with that.”

Then there are those who deny the potential for future health problems, some by adopting a “damn the torpedoes” attitude, sometimes before they’ve even finished treatment. Link recalls walking with a colleague past an oncology clinic waiting room and seeing two teenage boys — tall, athletic and bald — sharing a cigarette. “As we walked by, we said, ‘You know, you really shouldn’t be smoking,’ and one of them said, ‘What, am I gonna get cancer?’ ”

A recurring or secondary cancer — either leukemia or solid tumors — is a serious risk for survivors. And some survivors find they’re sterile, or have heart, lung or liver damage.

Magee knows that because of her Hodgkin’s treatment, she has an elevated risk for thyroid cancer and her heart may have been weakened. She’s religious about getting her annual checkup with Marina at the cancer survivors’ clinic, missing only once because of problems with her insurance. “I want to nip everything in the bud,” she says.

Survival as a way of life

Some survivors can’t ever ignore their disease, even briefly, because it isn’t yet curable. For these patients, survival is an ongoing process, less a matter of vanquishing a disease than of trying to rein it in.

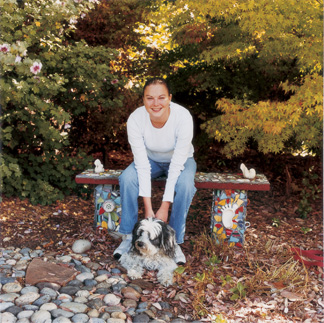

Cystic fibrosis is one of those diseases, and for Anna Modlin, 24, of Palo Alto, every day requires over an hour of physical therapy and a fistful of medications.

CF impairs the body’s production of secretions, so it can affect the lungs, the upper respiratory, gastrointestinal and reproductive tracts, and even perspiration.

Misty Keasler |

|

|

|

|

The lungs are most often affected, with the mucus coating the inside becoming so thick it blocks the airways, which then become infected and inflamed. Modlin’s main physical therapy is percussive therapy, what some call “the ketchup bottle technique.” “You literally pound on people in certain positions to dislodge the stuff and allow them to cough it out,” says Modlin’s doctor, Richard Moss, MD, professor of pediatrics and director of Packard’s cystic fibrosis center. In spite of treatment, 9 out of 10 patients succumb to respiratory failure.

But there has been great progress in combating CF. “At the time I started, the average life expectancy was probably in the neighborhood of 10 to 12 years of age,” says Moss, who’s been treating cystic fibrosis for 25 years. “Now it’s in the mid-30s.”

Usually CF is diagnosed in infancy, but not always, as no two people are affected the same way. Though caused by a single recessive gene, symptoms of CF are influenced by a slew of other genes and environmental factors. With Modlin, the tipoff came when she was 18 months old and started turning blue. She was in Stanford’s pediatric ICU, clinging to life on a ventilator, when she was diagnosed.

Initially after the diagnosis Modlin’s mom had to pound on her up to four times a day. “I was a pretty sick little kid,” says Modlin, but that changed when she started swimming at age 3. “I didn’t wake up in the middle of the night coughing anymore.” The onetime “sick little kid” eventually won a championship and later worked as a lifeguard.

Modlin still does percussive therapy twice a day, but a machine fills in for her mom. She wears an inflatable vest hooked to the shaking machine, and she uses a nebulizer, a pipelike device hooked to an air compressor, which emits a fine mist she inhales into her lungs to thin the mucus.

She also takes anti-inflammatory medicines, along with bronchodilators and antibiotics. Twice a year she takes a supplemental course of intravenous antibiotics for two weeks that triggers a flulike reaction the first few days. “It’s really horrible,” she says, “but I get through it.” And, before she eats, every time, she takes enzymes to aid her digestion.

It sounds like a lot to deal with, but Modlin says to her it’s background noise. “I mean, it seeps into everything, but it doesn’t hold me back,” she says. And, in many respects, she manages to live a pretty normal life. She has a bachelor’s degree, is working on a master’s in counseling psychology and has a boyfriend she often bicycles with. She still swims when she can and hopes to become a therapist. “I’ve always felt like I’ve been able to keep up, but just maybe in a modified way,” she says.

But Modlin has concerns most people her age don’t. She has to get ample rest to keep up her strength against infections, and though she has always attended school full time, she can’t work 40 hours a week. She’s living at home, partly due to the cost of school, but also for the daily support her family provides. And she has to have medical insurance; some CF medications cost over $10,000 a year.

Having health insurance doesn’t guarantee that patients get the treatment their doctor advocates, though. Moss says some HMOs balk at letting him see his patients quarterly. And there are other problems, he says, citing instances of patients taking a drug once a day, instead of twice, as prescribed, because they can’t afford their copay.

The type of insurance a patient has is also a factor. For example, says Moss, growing up in a smoking household, with passive smoke exposure, lowers a CF patient’s lifespan by 10 years; “if your health insurance is Medicaid, versus private, it has the same awful effect as secondhand smoke,” he says. But even the best insurance and medical care in the world can’t cure CF, or even halt it, and Modlin knows this.

As a kid, she went to a camp for children with CF. Modlin was 10 when the first of her fellow campers died.

Today, out of 10 kids who were in her cabin, all but Modlin and one other camper have either passed away or are ill enough to get lung transplants.

“It’s weird to think of myself being really sick because I haven’t had that experience. But I’ve seen friends who are really sick and so I know it will eventually happen.”

“I don’t envision being old,” she says. “But I see myself doing the things that I want to do. It’s probably different than regular people — but maybe it’s not, I don’t know.”

When her lungs eventually get too weak, Modlin hopes to get a lung transplant, though she knows that might offer only a temporary respite. Just half the CF patients who receive lung transplants are still living five years later.

“It’s not a cure by any means, but it gives you a couple extra years. And those years, you know, you’re perfectly healthy. You have lungs that work and you’ve never had lungs that work,” she says, adding with a chuckle, “It’s a good way to go out, you know?”

In spite of the uncertain outcome of lung transplants and a chronic shortage of lungs, Modlin says she’s still optimistic. “The longer you can push that away, the better medical treatment is,” she says. “If I can hold myself together for as long as I can, there’s got to be something.”

Future hopes

Her optimism isn’t unfounded. According to Moss, a tremendous number of new treatments are in the pipeline. “Everything from gene therapy to new forms of antibiotics,” he says, along with new anti-inflammatory agents, mucus-thinning drugs and, perhaps someday, stem cells.

Stem cells also hold promise for eventually treating other diseases, including cancer. For now, other advances are giving cancer survivors a healthier life after treatment, says Link, though that won’t alter Magee’s chances of complications.

She knows her Hodgkin’s disease could recur and she knows she might develop thyroid cancer. Still she maintains her feisty attitude. “I told Dr. Link, ‘One down and one to go.’ and he gives me that look of, ‘What?’ and I just kind of run my finger across my throat. He knew exactly what I was talking about — he just shakes his head.

“If, God forbid, I do get thyroid cancer I’ll make jokes about that too and get through the best I can.”

Comments? Contact Stanford Medicine at