Going beyond blood transfusions

Morhasen-Bello, MD |

|

|

|

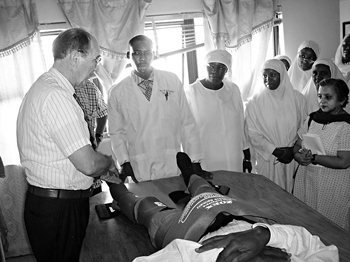

At Abdullahi Wase Hospital in Kano, Nigeria, Stanford’s Paul Hensleigh, left, shows how to remove the wet suit-like wrap he uses to save hemorrhaging patients’ lives. |

By ADITI RISBUD

When Paul Hensleigh, MD, opted for early retirement in 2000, it was a “John Elway type of retirement,” he recalls, chuckling. At the time, he was at the top of his game as professor of obstetrics and gynecology at Stanford and chief of obstetrics at Santa Clara Valley Medical Center. But Hensleigh was drawn away to tackle a terrible public health problem in developing nations that contributes to more than half of maternal deaths.

In the last five years, Hensleigh has traveled the world to aid patients suffering from obstetrical hemorrhaging — heavy bleeding during delivery which results in life-threatening shock. His game plan? A life-saving garment that resembles a dismantled wet suit. When a hemorrhaging patient is bundled up in the suit, compression-induced pressure slows blood loss, shuttling blood to the heart and brain and restoring function. Such a garment could do wonders for childbirth-related mortality rates in Nigeria, for example, where tens of thousands of women die in childbirth yearly because blood for transfusions is not readily available.

The military developed pressure garments during World War II to help pilots withstand drastic gravity force changes. A NASA researcher updated the design in 1991, creating a lightweight suit that wraps a person from ankle to navel in three-way stretch neoprene. After meeting the researcher, Hensleigh recognized the garment’s potential. The pressure induced by the garment pumps the equivalent of one to two liters of blood into the upper part of the body — “like getting a big transfusion in one minute,” says Hensleigh.

After achieving success with the garment in a Pakistani hospital in 2001, Hensleigh set out to develop efficacy studies. In 2003, he and UC-San Francisco safe motherhood expert Suellen Miller, PhD, received a MacArthur Foundation grant to conduct clinical trials. Hensleigh has spent much of the last few years testing the garment in Nigerian hospitals.

Conducting research in a politically unstable region certainly has its downside: Hensleigh was held hostage in 2004 at a hotel in Ibadan, taking a slug in the scalp and having his laptop stolen. But the incident hasn’t altered his plans — Hensleigh returned to Kano, Nigeria, this summer. So far, the results are overwhelmingly positive. “There’s been a lot of momentum,” he says. “Once people use it, they can see with their own eyes that it works.”

Comments? Contact Stanford Medicine at