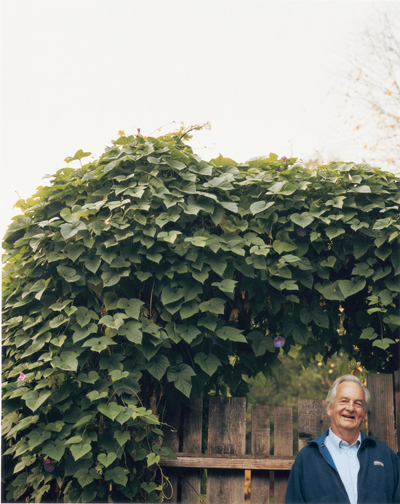

Halsted Holman started shaking up Stanford's medical school 45 years ago. It hasn't been the same since

Leslie Williamson |

|

|

|

By MITZI BAKER

Halsted Holman was a young guy with a big job. in 1959, he left his immunology research lab at the Rockefeller Institute for Medical Research to become, at 35, the chairman of the Department of Medicine at Stanford. His new task: bring the future to the Stanford School of Medicine. It was a time of great change for the school, as it was moving its entire shop from San Francisco to Palo Alto, aspiring to become a great research institution.

Little did Holman know that he would not only escort Stanford into the modern scientific age, but years later would call for another paradigm shift in medicine — one to combat what he views as the failure of laboratory science to resolve the most common health problems. Officially a retiree this year, you’d never guess it. He’s continuing his clinical practice, health services research and as always, is speaking his mind.

Half a century ago, on the heels of scientific advances stimulated by wartime research, some in the medical community began to see their work in a different light. This new view focused less on clinical treatments but instead poked and prodded, asking why and how disease happened. The approach came to be known as biomedicine.

At that time, Stanford radiology chair Henry Kaplan, MD, and pharmacology chair Avram Goldstein, MD, petitioned persuasively to then-university president Wallace Sterling that “Stanford should move dramatically to step aboard the beginnings of the biomedical revolution,” according to Holman, now the Guggenhime Professor of Medicine, Emeritus. “It became evident to a lot of people that biomedicine would begin to explain pathological processes and how they related to normal biological processes. This was not a completely new idea, but it had been a relatively small part of academic medicine except for a few schools on the East Coast.”

Kaplan and Goldstein argued that moving the medical school to the main campus, where doctors could interact easily with basic scientists and engineers, was an essential step to bring Stanford into the modern research age. “I also assume they saw that if they made that move, a large number of clinical departmental faculty members would stay behind, since all the patients were in San Francisco,” says Holman, “The faculty could be completely redeveloped.”

And redeveloped it was. As had been anticipated, many of the clinicians stayed in San Francisco — only about eight of the department’s faculty members made the move down — so Holman’s initial department began quite understaffed. Holman couldn’t have been more thrilled. What he had to offer his potential employees was a new building, lots of space and lots of money, thanks to a burgeoning National Institutes of Health initiative for stimulating biomedicine. “The situation was a window in academic history that doesn’t occur very often,” recalls Holman. “Clearly that isn’t the case now.”

Calling all upstarts

Holman set out to recruit faculty who shared his enthusiasm for biomedicine. These cutting-edge thinkers, he says, necessarily had to be young to be able to do both clinical medicine and laboratory science. “There were very few middle-aged or elderly physicians who knew bioscience then,” he says.

In 1961, Holman recruited 30-year-old Saul Rosenberg, MD, now the Maureen Lyles D’Ambrogio Professor in the School of Medicine, Emeritus, to the division of oncology, which he eventually came to lead. Rosenberg says he would never have been hired without Holman, as his strength was not known widely beyond radiation oncology and lymphoma research. Recruitment proved to be Holman’s strength. “To his credit, despite an unusual beginning, and no matter whether you agreed or disagreed with him, Hal created a very strong department of medicine by recognizing young people with great potential,” says Rosenberg. “And over the years, they have proven to be the strength of the school of medicine.”

The relative youth of the faculty meant there was little age difference between leadership and the trainees, a factor that Holman says led to the unexpected development of a rich social network of peers. “We not only did laboratory work together and saw patients together, but we went out together, played sports together,” he says. “The rigid, hierarchical life that was classical for academia just dissolved here, and we liked it that way.”

Infectious disease researcher Thomas Merigan, MD, the George and Lucy Becker Professor of Medicine, Emeritus, says that he came to Stanford in 1963 because he desired exactly the mix of basic training with clinical duties that Holman was offering. What Merigan got in addition to a department of medicine with a rigorous grounding in research, he says, was friends for life. “There was excitement about the growth of science in medicine then. We were all growing together and all wanted the best things for the group,” says Merigan, who was 29 years old when he arrived. “Hal had the ability to convey enthusiasm and optimism. Through the people he recruited, he created a camaraderie within the department that made people not want to leave. There was very low turnover in the first 10 years of the department.”

The solidarity of the new upstarts might have caused resentment from the old-school doctors who preferred the status quo. This potential snag in the smooth flow of transition was not a big problem, says Holman, mainly because so few of those who would have opposed the new-fangled ideas left their San Francisco clinics. But the few who did make the move did appear to resent the new situation a bit. “There was a sort of an atmosphere of the new coming in, taking over what the old had built,” says Holman. “The old had some difficulty acclimating to this.”

Even among the naysayers, Holman says that for the most part an air of good-natured banter reigned. He tells the story of surgery professor Roy Cohn, MD, who made the move down. “He was ready to argue at the drop of a hat about the stupid things that we were doing and how they undermined the tradition of medical care. He did this tongue in cheek because he liked to fight.

“Partly as a joke he insisted that the house officers had to get haircuts, as some of them had long hair. We said he had no basis to raise that issue, because he walked all around the hospital in his scrubs with his chest hair showing,” laughs Holman.

Holman was a lively character, and his strong stances eventually wore down those in charge.

“The differences in both his background and behavior were often very controversial,” says Rosenberg. “He came here as an unusually young chair of medicine at a time of great transition in the medical school and university and he then took on a very liberal position at a time when that was not a popular one here. With the Vietnam War, he took a strong viewpoint that was to the disfavor of the leadership.”

Amid speculation that Holman’s strong anti-Vietnam stance angered the leadership — and some grumbling that the department was suffering with respect to clinical care — the Holman era of the Department of Medicine came to an end in the early ’70s. Holman’s firing was as much political as it was academic, according to Rosenberg.

Holman concurs that his politics might have played a role, but that it wasn’t the whole story. “I think the basic motivation was that I was not sufficiently clinically oriented and that we needed to strengthen our clinical work as opposed to our bioscience. A lot of people, I think, felt that way,” he says. But even that contention was controversial. “Hal was always a clinician,” says Merigan. “He got his research materials from his patients and was always involved in their care. He was involved with ensuring clinical excellence, a theme he continues to this day.”

Personal change

Regardless of where he sat on the clinical/laboratory fence, Holman’s career turning point coincided with a major shift in his field of research. Ironically — because of the charges against him that he was not clinical enough — his research veered away from molecules and toward the larger picture of how patients with chronic diseases fare in the medical system.

“One of the things that occurred in the late ’60s and early ’70s was rising criticism of education in general. In medical education, people began to perceive that we weren’t completely solving problems with biomedicine and we had to look more creatively at how we studied disease and patients.”

Holman’s own story aptly reflects this trend. He came to Stanford as an immunologist, one of the original explorers of the molecules that react against the self — autoantibodies — at a time that the discovery of the molecules behind immune response was just beginning.

“When I arrived, I thought, ‘Wow, we are really going to be able to apply this stuff to clinical medicine. It is going to solve problems,’ ” he says. “But in the 10 years from 1960 to 1970, it became increasingly clear to me and many of my colleagues that a direct connection between laboratory science and clinical science looked less and less definitive. We weren’t really solving problems.”

During Holman’s first decade at Stanford, a whole new branch of immunology had developed, focusing on the cells of the immune system and their intricate interactions with the chemical signals they produce. Understanding antibodies apparently was not going to cure the autoimmune diseases such as lupus and rheumatoid arthritis. Holman was confronted with a choice: either learn cellular immunology or move on to a field other than immunology.

“New cellular immunologists were being trained everywhere by that time. If I were to become a refurbished immunologist able to do cellular work, I wouldn’t be contributing much. There would be younger people who were faster and better than I was,” he says. “Whereas the school had close to zero in the way of health services research, which interested me very much. So that’s what I decided to do.” Thus, Holman began to develop his chronic disease model, which has been his focus for the last three decades.

Holman recognized early on that ambulatory medicine — especially in the age of AIDS — was taking off and required new skills, notes Merigan. “His liberal and social approach to all matters is now carried over to outreach and new approaches to taking care of the underserved,” says Rosenberg.

Plotting the next revolution

According to Holman, over the past 30 years the nation’s principal health problem changed from acute disease, mainly infections, to chronic disease such as diabetes, heart disease and arthritis. Now nearly half of the U.S. population has a chronic medical condition. The care for these conditions consumes 78 percent of health-care dollars.

“The leadership in American academic medicine and in health policy has basically failed to respond to that change,” says Holman, “and as a result we have both ineffectiveness and inefficiency in health care.” The deficiencies as he sees them: inadequate quality of care, inadequate access to care (many are uninsured, but even insured people are having their benefits curtailed) and excessive cost. “The bottom line is the way in which medical offices are managed often stinks. We have to learn from business how to make things run efficiently.”

Holman published a commentary in the Journal of the American Medical Association last September outlining his chronic care model and his remedies for the problem. Part of the solution is for physicians to relinquish some control and encourage patients to play more of a role in their own care.

Empowering patients to manage their chronic health conditions has personal meaning to Holman, who has osteoarthritis. Working with professor of medicine Kate Lorig, PhD, he pioneered self-management programs for arthritis patients decades before he had the condition himself. “It’s been helpful to me, knowing how to put myself in the context of chronic illness and to begin to deal with it,” he says. “And since I work primarily with arthritis patients, I can use my own experience to help them understand how to deal with their problem.”

Looking back over his career and events in the world of medicine during that time, Holman sees a pattern: “The people at Stanford in the 1950s recognized the need for change. We weren’t doing a good job with health care and we couldn’t understand why people got sick. We had a chance to bring science in and enhance our understanding and we did. We changed the way we taught and to some extent how we practiced medicine. Our educational goal in the ’60s was to make the science relevant to clinical care. In a way, we viewed ourselves as bringing a new set of tools to clinical medicine.”

“Now the prevalence of chronic disease, which is the result of many forces, is requiring another shift. It’s basically recognizing that nothing is stable and that old solutions rarely continue to work.”

Comments? Contact Stanford Medicine at