It's all in your head

By KRISTA CONGER

Martin Angst, MD, smiles a little as he unlocks the door to a former operating room on the fourth floor of Stanford Hospital. The fluorescent lights illuminate what looks like a very large, very scary blue vinyl dental chair stationed under a bank of surgical spotlights in the center of the windowless room. Mysterious and vaguely sinister-looking machines line the walls and perch on two rolling carts near the chair. Two computers stand at attention on desks along one wall.

Angela Wyant |

|

|

|

“People often look a bit nervous when they first arrive,” he says as the door closes with a click. “They call it the torture chamber.”

The less-than-flattering nickname doesn’t faze the appropriately named Angst, who started the Human Experimental Pain Research Laboratory about 10 years ago to develop reproducible ways to test the effectiveness of new pain medications. But the assistant professor of anesthesia tries hard to quell his subjects’ unease before asking them to pony up their arms and legs for the good of science (and of their wallet — the usual payment is about $30 per hour). Relaxed, well-rested subjects rate the same unpleasant sensation as less painful than fearful, anxious or depressed people.

“We are trying to design a reliable measure of something that’s very subjective,” says Angst, who points out that animal data are of limited use for this type of study. “It’s a little like trying to measure happiness.”

Pain was once considered to be the ugly duckling of medicine — a disagreeable side-effect of trauma or disease to be quickly subdued with a prompt dose of anesthetic. But over the past several years, physicians and researchers have begun to realize that pain, which is processed in many of the same areas of the brain as stress, fear and anxiety, is as much an emotional as a sensory experience — a veritable poster child for the mind-body connection.

This blurring of the lines between the conscious and the unconscious requires a sophisticated therapeutic approach to address both the physical and mental roots of pain. Lucile Packard Children’s Hospital tackles the problem with a comprehensive pain-management clinic focused solely on kids, while Stanford Hospital offers both a multidisiplinary inpatient unit — one of only three in the country — as well as a comprehensive outpatient clinic. The clinics at both hospitals combine pharmacological, psychological and behavioral approaches to help patients with a host of ailments. Although a lucky few leave pain-free, most are taught coping mechanisms that will allow them to resume their lives, controlling rather than being controlled by their pain.

Elana Hunter is all too familiar with how chronic pain can hijack a normal life. The formerly active 10-year-old was preparing to go rollerblading with her family one day last spring when she noticed that her left wrist hurt. She’d had no trouble with it the day before when playing on the parallel bars, so the sudden tenderness was a surprise.

“I jokingly told her that her wrist was supposed to hurt after we went rollerblading, not before,” says Elana’s mother, Tessa Hunter. She and Elana’s father, Adolph, quickly realized that Elana’s rapidly worsening pain was no laughing matter. But they had no idea of the weeks-long odyssey that would eventually land her in the pediatric pain management clinic at the children’s hospital.

Elana has complex regional pain syndrome, or CRPS, otherwise known as reflex sympathetic dystrophy. The disorder often starts with a seemingly trivial injury that appears to heal normally but is followed by severe burning pain in the affected limb that persists — sometimes for years. Although it’s not known what causes CRPS, physicians agree that it’s likely the result of abnormal nerve impulses in the brain that are interpreted as pain in the now-normal limb.

“This spontaneous, or neuropathic pain, is real,” says Elana’s doctor, Elliot Krane, MD, director of the children’s hospital’s pediatric pain management clinic. “There are obvious secondary changes that occur in the limb: the muscles weaken, it feels cold and the skin becomes abnormal.” At one point Elana’s family watched in horror as the skin on her arm turned white and began to peel in a matter of minutes.

If it’s my stubbed toe calling, I’m not in

Elana’s condition is an extreme example of chronic pain, which more often manifests itself as headaches, backaches or abdominal pain. But many types of chronic pain — with the exception of that caused by an ongoing disease process like cancer or diabetes — result at least in part from overly active neurons in the pain-sensing regions of the brain reacting to imagined distress calls from the body. And when it comes to pain, the brain rules.

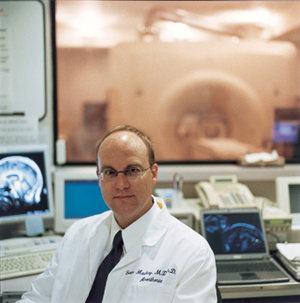

“Most people who burn their hand or stub their toe think ‘Oh, that’s painful,’” says pain researcher Sean Mackey, MD, PhD, assistant professor of anesthesiology. “But that is just an electrochemical signal shooting up their nerves to their spinal cord, and then into their brain. It’s not pain until it’s processed and perceived as pain by the brain.”

Most of us react to this immediate, or acute, pain by quickly moving our hand or foot out of peril: a two-way conversation between brain and body with obvious biological value. But the interaction doesn’t end there.

“The central nervous system used to be thought of as a hard-wired part of the body, sort of like telephone wires,” says Krane. “Now we are beginning to realize that it’s actually extremely plastic, and can remodel in response to stimuli.”

Angela Wyant |

|

|

|

We’re all familiar with one temporary modification. That first distress call from the stubbed toe to your brain paves the way for others, leaving the injured area tender and red. This heightened sensitivity, or hyperalgesia, causes you to favor a bruise, scrape or sprain until it’s healed.

But sometimes this survival tactic goes awry, leaving sufferers with chronic pain long after the original damage has been repaired. It’s as if the phone rings incessantly even though there’s nobody on the line. The brain’s pain center answers repeatedly, registering pain and dictating physiological changes in response.

Amputees often have a similar experience. The very distinct, yet obviously impossible, prickling or burning pain they describe in their missing limbs is thought to be due to random firings of the now-unneeded neurons in their brains formerly dedicated to processing sensory input from the amputated arm or leg. This so-called “phantom pain” can occur spontaneously, or it can be induced by stroking a part of the body, such as the face, that connects to neurons in the brain bordering the now-useless section.

Although controlling such sensory remodeling is a daunting task, it is sometimes possible to use spinal anesthesia to keep painful signals from planned events such as surgery from ever reaching the brain. This technique, called pre-emptive analgesia, has been shown to reduce the amount of pain medications needed after the procedure.

But this research has limited value for someone like Elana, whose precipitating injury was unanticipated, or for the many people suffering from chronic pain. According to a 2005 Stanford University Medical Center/USA Today/ABC News poll nearly 1 in 5 American adults say they suffer from chronic pain.

Doctors are only now getting a glimpse of what the long-term effects of chronic pain might be. Some studies suggest that in adults the areas of the brain responsible for perceiving pain might shrink over time. In children, the energy required to maintain a pain response might interfere with normal brain development. Ongoing pain might also compromise the body’s ability to defend itself.

“We’re learning that pain has a huge impact on our global functioning,” says Mackey. “At the time that we most need our bodies to fight off an infection or to battle cancer, pain may be depressing our natural immune responses.” And of course, ongoing pain can drastically affect a patient’s mood.

“The mind-body connection in pain management is just so important,” says Krane. “Chronic pain often leaves formerly active people depressed, and depressed people are even less tolerant of discomfort and pain. On the other hand, we know that the brain can produce a whole host of analgesic compounds, and that it’s possible to teach patients ways to use their brains to stimulate the release of these factors.”

The hospitals’ pain-management clinics combine physical therapy and medication with relaxation and distraction techniques, biofeedback and behavioral modification to lessen anxiety and teach patients how to work through their pain.

“Unfortunately, we don’t have a sure-fire cure for chronic pain,” says Raymond Gaeta, MD, associate professor of anesthesia and Krane’s counterpart at the adult hospital. “But we do have options,” says the Stanford medical alumnus, class of ’85. “We can teach people how to deal with the consequences of their pain. A lot of people are disabled by their fear of pain and their concern about their future. Healing that can go a long way to give them self-confidence and efficacy.”

Mind over what’s the matter

Angela Wyant |

|

|

|

“Don’t forget your belly breathing, Elana,” says one of the children’s hospital’s physical therapists, Susan Spence, as the girl works to tense and release the muscles in her lower left arm lying slack in her lap. Electrodes taped to Elana's forearm translate tiny muscle contractions into movement of a simulated basket across the bottom of a computer screen. She’s trying to catch colored “eggs” falling from the top of the screen.

“It’s hard,” says Elana, for whom even these imperceptible arm movements are very painful. She and Spence set a goal of 30 eggs, and Elana’s visibly tired at the end of the game. Later Spence attaches a temperature sensor to one of Elana’s fingers and a line appears on the screen. She instructs Elana to think about increasing the blood flow to her finger, which can help relieve pain and tension in an afflicted limb. The girl appears mystified, but over the next few minutes the line on the screen begins to creep up.

“Do you know how you did that?” asks Spence. “No,” says Elana. “I’m just sitting here staring at the screen.”

Mackey wouldn’t be surprised to learn about Elana’s new-found talent. His recent research has shown that it’s possible to affect how you perceive pain simply by seeing it on a computer screen.

“We believe that the experience of pain can be divided into two relatively large areas in the brain,” says Mackey, “one that responds to sensory input that defines what part of the body is in pain and how it feels — whether it is burning, stabbing or prickling, for example — and one that processes the emotional aspect of pain — how unpleasant it is and how much the person wants to get away from the pain.” Mackey uses a technique called functional magnetic resonance imaging to peer at “brains on pain.”

“We are literally seeing how pain is processed and perceived, and what happens to the brain in the face of chronic pain,” he says. In one experiment he placed a heated probe on the arms of healthy volunteers. A real-time fMRI scan of their brains showed the pain as an angry red and yellow blotch in a sea of gray. The study subjects found that they could shrink the colored area and their perception of pain just by concentrating on the image.

How? Nobody knows

Angela Wyant |

|

|

|

“We give them instructions about how to get started,” says Mackey, “like focusing inward or viewing the pain differently — perhaps imagining a burning sensation as something more soothing, like being in a sauna — and then we turn them loose. After multiple training sessions they are able to control the pain, but they don’t really know how they’re doing it.” Mackey found that chronic pain patients could also tamp down their responses. Their experience left them elated.

“Many study subjects came out of the experiment saying, ‘This was an amazing experience. For the first time I could see the pain in my brain, and I could control it,’ ” says Mackey. “That sense of control is very empowering for pain patients.”

Such high-tech solutions are not available or practical for everyone with chronic pain. Most physicians have to rely on self-reporting by patients to assess new pain treatments — a tricky proposition.

“We don’t have a language to explain the color blue, or what a strawberry really tastes like,” says Mackey. “Therefore, for now, pain is what the patient says it is, and we try to treat it on those terms.” But the standard method of rating pain intensity on a scale of one to 10, where 10 represents the most pain a person can tolerate, isn’t always reliable. What might be uncomfortable one day might be intolerable the next, depending on the subject’s level of anxiety, sleepiness or overall feeling of well-being.

Quantifying pain can be especially difficult for children, who often seem to overreact to painful circumstances. It’s difficult to tell if this is because they have little or no context with which to judge their pain, or if something about their developing nervous systems makes them feel pain more keenly than adults. But regardless, it’s important to take their reports at face value. And there are some advantages to treating children.

“Pain is what the child says it is,” says Krane, a professor of anesthesia. “But children also tend to be less skeptical and more adept than adults at some of the biofeedback and relaxation techniques that we teach.” For example, Elana’s treatment has increased her wrist’s effective range of movement and reduced her pain from a nine on the pain scale to a four or five. She and her parents are determined to keep working toward continued improvement so that she can be in school full time.

Although Elana is making steady progress, pain researchers agree that it’s nearly impossible to reliably measure the success or failure of any kind of pain management, or to develop more effective interventions, without an unbiased yardstick like the kind Angst, the pain lab director, is working on.

Pain connoisseurship

Angela Wyant |

|

|

|

Angst uses a cornucopia of unpleasantness to study how individuals rate pain: a heated probe, an icy water bath, an electrical current and simulated sunburn, among other things. He and others have found that both healthy volunteers and chronic pain patients are much better at ranking their pain after they’ve experienced their maximum. In the heated probe test, the probe is held to the subject’s skin and heated at one degree Celsius per second until the subject terminates the experiment by pressing a button on a hand-held control. (The probe is limited to a maximum 52 degrees to prevent blistering, and any study subject can drop out at anytime.) After a few go-rounds, most subjects can use the pain intensity scale very reliably, consistently assigning the same rating to the same temperature, for example.

“It’s like calibrating a thermometer,” says Angst.

Although it’s not practical yet to do such “perceptional calibration” studies in a clinical setting, they do allow Angst to test drugs and other treatments. While he hopes to use the data to single out the most promising interventions for further study, he’s also learned some interesting things about existing pain treatments.

He’s found that long-term, high-dose users of morphine and other opioids are actually more sensitive to certain types of pain stimuli, such as icy water, than are unmedicated participants. That might be the result of their body’s struggle to overcome the effect of the pain-blocking medication. The higher the doses, the more sensitive the patient.

“Pain has a meaning and a function,” says Angst. “If the body up-regulates pain pathways in response to increasing doses of opioids, maybe we can use the opposite approach. If we block the body’s natural pain-inhibiting systems for a few days before a painful intervention like surgery, maybe they will ramp up and be more effective at alleviating pain after the block is removed.” The idea might be unconventional, but it’s time for a new approach, he says.

“When I went to medical school in the ’80s, pain was thought of as a beast you were trying to wrestle down to the floor with medication. The philosophy was ‘if it bucks, give more,’ ” says Angst. But the prevelance of pain demands a new approach. “We can’t just ignore the central nervous system as if it were hard-wired. It’s dynamic, and we need to engage it in an intelligent way,” he says.

Other pain researchers agree. “We’re still working on the fundamental science of pain transmission and perception,” says Gaeta, who’s encouraged by discoveries of molecules involved in pain transmission and perception. Angst is investigating whether measuring the levels of pain-signaling molecules in affected tissues can guide the development of new drugs and therapies. In addition to the molecular approach, the work of Mackey and others to help people control their pain represents a promising direction.

“Imagine taking this experience to the next level by showing subjects an image of a specific pattern of brain activity and asking them to match it with their own brains,” says Mackey. “Could this exercise extend to other clinical situations such as depression and anxiety? Perhaps it will one day be possible to pump up your hippocampus to improve your memory.”

The idea of this type of “brain camp” is undeniably appealing, albeit futuristic. It may happen sooner than you think, however. Pain researchers have seen remarkable progress in pain management during the past decade and a half.

“Although we are still practicing in the dark ages, we’ve made incredible strides,” says Mackey. “It’s still a young science. We’re going to look back in another 15 years and ask ‘What were we doing? We were fusing backs, burning nerves and using substances with terrible side effects.’ ” Mackey believes the field will soon start to gravitate toward individualized therapies, targeted drugs and pharmaceutical agents matched to a patient’s genetic and biochemical profile.

“We’re also going to learn a tremendous amount about the role of the brain and spinal cord in the generation of pain in humans,” he says. “We will be able to use our growing awareness of the mind-body connection to target specific areas of the brain and use molecular biology, biofeedback or medications to alter the neuroplasticity associated with chronic pain to return patients to some degree of normalcy.”

Pain — our own and that of others — binds us together with the thread of common experience. Pain is deep. It can keep us safe or make us miserable. But, as Angst, Krane, Mackey and Gaeta are finding, the key to unlocking pain’s split personality might lie in a platitude: It is all in your head.

Comments? Contact Stanford Medicine at