The science and politics of stem cell research

Illustration: Guy

Billout |

|

|

|

By MICHELLE L. BRANDT

![]() SIDEBAR

1: Stem cell primer

SIDEBAR

1: Stem cell primer

![]() SIDEBAR

2: Taking the initiative

SIDEBAR

2: Taking the initiative

Stanford physician Michael Lyons, MD, is not a stem cell researcher. But when the Connecticut House Speaker recently called him to discuss her "cautious, maybe even negative, feelings" about a state bill that would endorse embryonic stem cell research, the Stanford genetics fellow was happy to oblige. The state lawmaker felt uneasy about portions of the bill, so Lyons patiently defined complex scientific terms, clarified the differences between this type of research and reproductive cloning, and outlined what he saw as the merits of the work.

By the end of the conversation he had convinced his mom that she should support the legislation.

Lyons and his mother, Speaker Moira Lyons, are just two of many to dive into the debate surrounding stem cells, undeveloped cells that can be coaxed into growing into any kind of tissue. Stem cells are so small that they can't be seen with the naked eye, yet they tend to cause mass confusion and evoke the largest of responses. In fact, Moira Lyons blames the bill's eventual failure to pass in the Connecticut House on legislators' confusion over terminology. A U.S. senator recently called the field of study "the most promising research in health care, perhaps in the history of the world;" the U.S. Conference of Bishops, meanwhile, has branded the work "morally unacceptable."

President George W. Bush entered the fray when he announced his policy to limit federal funding of embryonic stem cell research in 2001; Congress has been batting around bills about this research ever since. States like Connecticut have gotten in on the act, too: More than 100 bills, either condemning or supporting the research, have been introduced in 33 different states in the past year alone. And residents of California now find themselves in the midst of a campaign involving a bond initiative that would provide $3 billion in state funding for the research.

Universities are also paying attention to stem cell research. Stanford was one of the first institutions in the country to dedicate a program to this area of study. Its Institute for Cancer/Stem Cell Biology and Medicine was launched in December 2002, and the announcement triggered extensive public discussion.

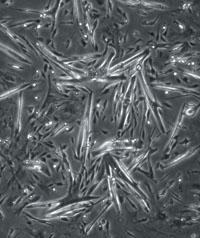

| A cardiac muscle cell colony derived from tissue grown from an embryonic stem cell. |  |

|

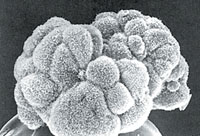

| A blastocyst seen through a light microscope. The inner cell mass, consisting of stem cells, is visible at the top. |  |

|

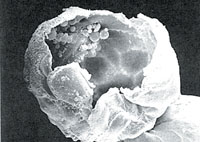

| Another view of a blastocyst, this one an image captured with an electron microscope. It's resting on a pinhead. |  |

|

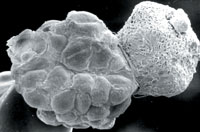

| This blastocyst is broken open, its hollow center revealed. The cells attached to the inner wall are stem cells. |  |

|

| A blastocyst, emerging from its shell. |  |

|

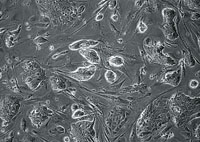

| Human embryonic stem cells, growing in culture. |  |

|

Why the fuss?

Stem cells are considered the building blocks of the body, and many scientists and patient-advocacy groups believe in what one stem cell researcher referred to as embryonic stem cells' "potentially limitless potential." Because embryonic stem cells are pluripotent, meaning they can give rise to almost all cell types of the body, scientists believe they can use them to create a supply of replacement cells for injured or diseased tissues. The hope is that the cells can eventually be used to cure or treat a variety of ailments, such as diabetes and Parkinson's disease. Adult stem cells have also shown promise, but scientists disagree over their therapeutic value.

Embryonic stem cells are taken from blastocysts -- the collection of cells that develops over the four to five days after an egg is fertilized. Most often these tiny balls of cells originate from fertility clinics, donated by couples who created them for fertility treatment but ultimately didn't use them. Although stem cell researchers do not implant these cells in a womb, some conservatives and religious groups liken the harvesting process, which destroys the blastocyst, to abortion.

"The division between those who support human embryonic stem cell research and those who oppose it comes down, for the most part, to a religious belief about when life begins," notes Philip Pizzo, MD, dean of Stanford's medical school. Indeed, the biggest problem with embryonic stem cell research for Carole Hogan, spokesperson for the California Catholic Conference, is what she considers the destruction of human life.

"There's no way to get stem cells out without killing embryos," says Hogan. "An embryo is the earliest form of human life -- it's not just a fertilized egg. People who are in support [of this research] minimize the embryo and make it sound like a building block or product."

William Hurlbut, MD, (SM '74), a consulting professor in Stanford's Program in Human Biology and a member of President Bush's Council on Bioethics, agrees with Hogan. "I do not believe that a decent society builds the foundations of its biomedical science on the creation and destruction of human embryos," says Hurlbut, adding that he favors advancing the research in ways that address these moral concerns.

But most research proponents feel that the rights of a blastocyst are far outweighed by the need for new treatments and potential cures. And they do not consider blastocysts to be human beings per se. "I believe that the human embryo has some moral status, but it is quite different from the status of a living, breathing human who is desperately ill," explains Hank Greely, JD, a law professor with the Stanford Center for Biomedical Ethics. "I think human life is too sacred to let it be lost for lack of pursuing promising research avenues."

Bush faced his own moral and political dilemma regarding this issue, saying in 2001 that "even the most noble ends do not justify any means." In August of that year, he announced that federal funding for stem cell research would be limited to a small number of cell colonies, or lines, that had already been taken from human embryos. He based his decision on his belief that taxpayer funds should not support "further destruction of human embryos."

While some praised Bush's executive order ("It was a Solomonic decision," says Hogan), others labeled it troubling and even dangerous. "It felt like a restriction that could be life-threatening for me and a lot of other people," recalls Idelle Datlof, a multiple sclerosis patient and founder of the pro-research, nonprofit Stem Cell Action Network.

Nobel laureate and emeritus faculty member Paul Berg, PhD, agrees with Datlof. "The president conceded that stem cell research had enormous scientific promise and had the potential to alleviate very serious diseases," he says. "And yet what he did was impose constraints that essentially eliminate almost all of those possibilities."

At the time of Bush's announcement, the administration said as many as 78 cell lines were available for researchers. In fact, Bush was wrong and the number of available lines was actually much smaller. Some of the lines were not useable; others -- because of licensing or exporting restrictions -- have not been accessible. "The number of eligible stem cell lines got smaller and smaller and the restrictions on obtaining the available stem lines were much more onerous than anyone imagined," says Berg, who has been aggressively lobbying for a policy change.

Nineteen lines are currently available, but they all carry a risk of viral contamination because they were grown in culture dishes coated with mouse cells, a method that nourishes the stem cells and helps them grow. The chance that unidentified mouse viruses could cross species and harm humans renders these cell lines "useless for anyone interested in developing therapies," says Berg.

He and others argue that these lines are inadequate. "When you're trying to develop therapies that are highly individualistic for almost 2 million Americans, 19 stem cell lines is clearly a tiny fraction of what you need," says Dan Perry, president of the Coalition for the Advancement of Medical Research, a stem cell research advocacy group.

Despite the federal funding shortfall, most researchers have vowed to press on with their work. "The government is making ideological decisions to ban or not fund the kinds of research that certainly will affect the lives of people; to sit by and not do anything is against the medical oath that I took," says Irving Weissman, MD, (SM '65), director of Stanford's stem cell institute, who has publicly testified that some studies cannot be conducted with the 78 allowable stem cell lines or with adult stem cells. "The highest priority I have is the health of patients."

Weissman says he plans to pursue all avenues of stem cell research, and the university, which received $12 million in seed money for the institute from a private donor in 2002, has looked to additional private donations for support. Other universities have followed suit: Harvard is raising $100 million for its stem cell institute, and the University of Minnesota and University of Wisconsin are among the public institutions using private funding for embryonic stem cell research.

Yet many argue that public funding is critical to the future of this research. One reason: most scientists agree that public accountability is crucial for such an important -- and controversial -- line of work, yet private-supported research operates outside the rules that govern NIH-funded work. Another reason: there is only so much private money to go around. "It's reached the point where the federal funding policy is affecting the ability of researchers to conduct as much research as they would like," says Larry Soler, director of government relations for the Juvenile Diabetes Research Foundation.

Pizzo agrees. "We have been fortunate in receiving one very large anonymous donation and several smaller ones, but we need considerably more dollars," he says. "The limits by the NIH on funding for stem cell biology have a chilling effect on scientific development."

Many worry that this chill could have a negative effect not just on science but on U.S. industry. Numerous countries, including England, Australia and Singapore, are pursuing this research aggressively, and earlier this year South Korean researchers became the first to develop human stem cell lines using somatic cell nuclear transfer -- a technique that involves inserting genetic material from a body cell into an egg cell and stimulating the egg cell to divide. This advancement means researchers have for the first time a way to control the genetic makeup of a stem cell line. "If our restrictions remain, the U.S. will cease to be a player in this arena," warns Pizzo.

"It wasn't great that one of the first big breakthroughs happened in South Korea," concurs David Magnus, PhD, co-director of the Stanford Center for Biomedical Ethics. "If we don't do this research, other places will."

Fighting for stem cell research

Concerned about the future of stem cell research in this country, patient-advocacy groups began lobbying Congress to take action following Bush's announcement. In late spring of this year, 206 U.S. representatives and 58 U.S. senators penned two letters to the president asking him to federally fund stem cell research on spare embryos stored in fertility clinics. One of the signatories was Sen. John Kerry, the Democratic presidential nominee.

The call for a federal policy change was intensified by the June death of former President Ronald Reagan, who suffered from Alzheimer's disease, and the public remarks made by former first lady Nancy Reagan. Shortly before her husband's death, Reagan expressed her support of embryonic stem cell research at a high-profile diabetes fund-raising event. "I just don't see how we can turn our backs on [stem cell research] -- there are just so many diseases that can be cured, or at least helped," she told the audience. Weeks after his father's burial, Ron Reagan announced on a CNN talkshow that he expects his mother will continue to push for stem cell research.

The support offered by Nancy Reagan, a conservative Republican whose husband was staunchly pro-life, and by numerous prominent, pro-life Republicans demonstrates that the issue crosses party lines, says Soler of the juvenile diabetes foundation. Ryan Adesnik, Stanford's director of federal government relations, agrees and says he believes the issue is becoming "less Democrat versus Republican every day."

The debate remains highly politicized, though, and people tend to use dramatic language when discussing the issue. "Politics drive you to say 'this is spectacularly wonderful' on one hand or 'this is vile' on the other," notes Stanford law professor Greely. "Careful, intermediate positions are not favored, either by political process or the press."

Some worry that the hyperbolic nature of activists' sound bites might do a disservice to laypeople, who could assume stem cell research will lead to a cure for every major disease. "I do worry that the politics of all this is creating unrealistic expectations," comments bioethics council member Hurlbut. "It does not seem honorable to say that stem cells will cure Alzheimer's disease when we are not completely clear what causes it."

Catherine Verfaillie, MD, director of the University of Minnesota Stem Cell Institute, agrees. "I think it's important for people to have realistic expectations about this research," she says. "We are still in the infant stages of this research and it's far too early to tell what will and will not be possible."

Still, most researchers in the field desire at the least the opportunity to determine what is and is not possible -- and the research advocates' war cries have grown louder since Reagan's death. Legislation introduced in the U.S. House in June would expand Bush's policy by allowing federal funding for research using "leftover" embryos from in vitro fertilization treatments. And many people spoke out against the government's recently announced plan to open a "national bank" to grow the 19 available lines. New lines, not a bank of old ones, are what scientists really need to advance science, their thinking goes.

Most observers believe that we will see no policy changes coming from the White House before the upcoming election, but some stem cell proponents are optimistic for the future. "One way or another the policy is going to be expanded," says Soler. "It's a just a matter of when."

But federal funding of research isn't the only political issue; the other is the actual criminalization of a technique to create new embryonic stem cell lines. Even some proponents of embryonic stem cell research have concerns about using somatic cell nuclear transfer, which is also the first step in reproductive cloning, to create the new lines. Some worry that it could open the door for reproductive cloning, a technique that is almost unanimously scorned by the scientific community. This, in fact, was one of Moira Lyons' biggest concerns when she called her son for advice on the Connecticut bill.

Weissman and other scientists argue that reproductive cloning should be banned, as it is in a handful of states, but that nuclear transfer to create new stem cell lines for research and therapy -- known by the misnomer "therapeutic cloning" -- should remain legal. Without the technique, researchers would be left with surplus embryos from fertility clinics as their only source of stem cells. These embryos are a poor source for medical research since most carry only the genes of healthy white couples. Nuclear transfer allows researchers to use nuclei from non-white patients and patients with genetic diseases to develop pluripotent stem cell lines, thus better representing the diversity of the world's population.

Weissman and others also stress that they are not seeking to recreate life and that nuclear transfer is far different from what is required to make batches of "Mini-Me's."

"With therapeutic cloning, no egg and sperm ever meet, there is no implantation of a cloned structure into the uterus and there is no fetus, no pregnancy, no birth," says Perry, the stem cell research advocacy group president. "Yet for ideological reasons some blur the line between reproductive cloning and therapeutic cloning."

The U.S. House of Representatives twice passed a bill that would ban both nuclear transfer and reproductive cloning, and the U.S. Senate has considered a similar bill. Under the bills, which are supported by the White House, violators would be subject to imprisonment of up to 10 years and penalties of $1 million or more.

This legislation frightens Weissman. "Before one enacts the first ban on biomedical research in U.S. history based on ideology, not safety, we should realize what will be lost," he recently testified in Congress. "[We should] think deeply about the political, medical, societal, commercial and moral consequences of such a ban."

With the apparent stalling of the U.S. Senate bill, people on both sides of the debate turned their attention to the states. In 2003, California became the first state to enact a law permitting embryonic stem cell research and allowing for the donation and destruction of embryos. (State Sen. Deborah Ortiz, the law's author, said she was motivated by the U.S. Senate's efforts to criminalize the research -- something she found "crazy.") New Jersey recently passed a similar law; 10 other states have considered similar legislation in the past year. On the other side of the coin, five states currently prohibit nuclear transfer research.

California might be a research-friendly state, but -- due to the state's budget woes -- no state-level funding for stem cell research exists. To create more resources, a group of activists has designed the California Stem Cell Research and Cures Initiative, a November ballot measure that would fund stem cell research, both embryonic and adult, with $3 billion in state bonds over 10 years. If passed, the measure would make California the largest source of state funding for stem cell research and would, many say, dramatically invigorate the field.

"It would be a huge development that would rattle windowpanes in Washington," says stem cell research advocate Perry. "It would make California a world player in regenerative medicine and this would have a blow-back effect, encouraging other states and the federal government."

Berg, who along with Weissman has campaigned for the initiative, concurs. "Is Massachusetts, home to Harvard and MIT, going to stand by and watch California? I think there will be enormous pressure for other state legislatures to commit funding."

Initiative supporters argue that this is an economic development issue as much as a science policy one. Robert Klein, president and chair of the initiative campaign, has said that as much as $70 million in tax revenues from construction and new jobs could be generated for the state, which represents the fifth-largest economy in the world. Proponents also say that the development of treatments and cures could drastically reduce the state's enormous health-care bills.

To date, Gov. Arnold Schwarzenegger has not taken a position on the initiative, but the measure has the backing of numerous heavyweights, including the California Medical Association, American Diabetes Association and the National Coalition for Cancer Research. Business groups, such as the Los Angeles Area Chamber of Commerce and the San Jose Silicon Valley Chamber of Commerce, have also endorsed it. Still, some have expressed concerns with the initiative's hefty price tag.

"We'd like to see embryonic stem cell research publicly funded and publicly regulated," says Marcy Darnovsky, MD, associate director of the Oakland-based Center for Genetics and Society, a pro-choice public interest organization focused on reproductive and genetic technologies. "But we doubt that $3 billion for a still unproven line of research is justified -- especially when 7 million Californians have no health insurance and the state is in a serious fiscal crunch."

Groups that oppose the initiative on moral reasons have begun to organize and campaign against the measure. The California Catholic Conference's Hogan says she wants to spread the word that "there is no cure around the corner" (she points out that no treatments or cures have been discovered with embryonic stem cell research) and that society has a duty to stop treating human life as if it's expendable. "It's the scientist's job to push the envelope and it's the society's job to say we need more discussion," she says. "Just because scientists say 'we can do this' doesn't mean we should do it."

Initiative supporters have said early polling results are promising, giving state lawmakers like Ortiz reason to remain hopeful about the initiative's chances. "Thank God for the average person who believes in the rightness and correctness and righteousness of this issue," says Ortiz. "They'll show us we need to be courageous and move forward."

The battle continues in other states. Although most states' legislative sessions have ended, legislators have vowed to press on with this issue next year. Connecticut's bill endorsing embryonic stem cell research did not pass this time around, but Connecticut Speaker Moira Lyons says she's positive it will come up next year. "There are enough people who support the concept."

As for the national landscape, it could look quite different after Nov. 2. Many experts point to Kerry's support of stem cell research and say that U.S. policy could drastically change should he be elected.

Many scientists and research advocates, meanwhile, believe that the inevitable research breakthrough will squelch the debate altogether. "I believe the science will accomplish something so helpful for people with diabetes, Parkinson's or one of the many diseases that afflict American families that it will be difficult to stop it," says Stanford government affairs director Adesnik.

"In the end the science will prevail," agrees Pizzo. "The big question is where it will take place."

Comments? Contact Stanford Medicine at