Stanford doctors take to talking politics

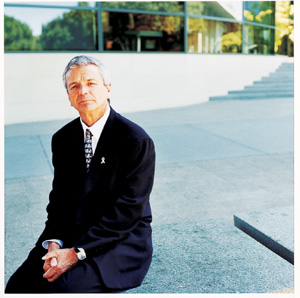

Photo: Amanda Marsalis |

|

|

|

By RUTHANN RICHTER

![]() SIDEBAR: Tips for pushing your agenda

SIDEBAR: Tips for pushing your agenda

Pediatrician Charles Prober, MD, had long been frustrated that most of the drugs he and his colleagues gave to their young patients had been studied only in adults, not children. So a year ago, he went to Washington to lobby congressional staff about the need to require testing of prescription drugs in children.

"It felt compelling to be involved with people who could influence things," says Prober, professor of pediatrics, of medicine and of microbiology and immunology.

As a result of efforts by him and others, the Pediatric Research Equity Act was signed into law in December 2003, requiring that new drugs be assessed for their safety and effectiveness in children.

Not many scientists are comfortable stepping into the world of politics. And talking politics is hard work, no question. But Prober says the potential to shape change on a societal scale makes it worthwhile. And the experience of walking the halls of Congress is less intimidating than you might imagine, he says.

More faculty and students at the School of Medicine are recognizing the value of advocacy and are taking on political issues. Since 2000, the pediatric residency has required training in advocacy, with service projects as part of the curriculum. And starting this year, all medical students train in advocacy as well -- an addition to the curriculum that came at the students' request.

Prober has been involved in advocacy since the late 1970s when he met with members of the Canadian and U.S. Red Cross to alert them to the danger HIV posed to blood supplies. More recently, he worked with the American Academy of Pediatrics to devise recommendations on childhood vaccination and infection control.

Now he's considering becoming involved in the issue of childhood obesity. Legislation barring sales of junk food in schools might be the most effective way to rein in children's eating habits, he thinks.

Whatever the message, Prober says it's best given in simple, direct language. He says history is rife with stories of great scientists whose discoveries went unnoticed for years because "they botched their message by an inability to communicate." He cites the example of 19th century Hungarian obstetrician Ignaz Semmelweis, who found that physician hand-washing could greatly reduce deadly infections among pregnant women in the delivery room. But Semmelweis' message took decades to take hold because he was so clumsy in communicating what he found.

Prober advises undergraduates to take courses in writing, communications and rhetoric to help get their message across. "They need the tools to deliver the message or it will die on the vine or be delayed 100 years," he says.

Action plan: tips for pushing your agenda

Charles Prober, MD, has worked the halls of Washington, D.C., to bring about policy changes to improve children's health. Admittedly, his credentials help: He's a professor at Stanford and scientific director of the Glaser Pediatric Research Network. But the world of advocacy is open to all. Prober has these tips for people who want to put their passion for an issue into action.

- If you work in an institution that offers media training, take advantage of it. Media training can help you hone your thoughts and develop effective ways to express them through print and broadcast outlets.

- Align yourself with groups that are key to your message. This could be a trade group like the American Academy of Pediatrics or a governmental organization like the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

- Coordinate with colleagues or others who are of like mind. Work with them to develop a consistent message.

- Identify resources that can help you get your message out. At Stanford, these include the Office of Communication & Public Affairs and the Office of Government Relations.

Comments? Contact Stanford Medicine at