If they'd only get directions, they'd make it home sooner

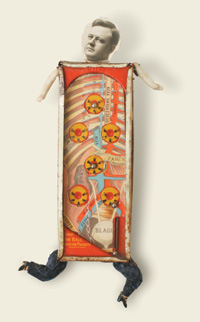

Illustration:

Polly Becker |

|

|

|

By AMY ADAMS

If the body is an entire world, then cells within it are the flora and fauna residing in their particular niches. A lingering question has been how cells transplanted into this new environment navigate to the appropriate ecosystem. Do they wander the body trying out several nooks or do they make a beeline for their ultimate home?

Knowing the answer to this question could increase the effectiveness of stem cell transplants, which doctors use to replace bone marrow cells lost during cancer treatment and, experimentally, to treat Parkinson's and Alzheimer's diseases. By manipulating "come hither" signals, the doctors could inject stem cells and speed their arrival to a location where they could help repair damaged tissue.

In the first set of experiments to follow a cell's migration, researchers at Stanford watched as a single transplanted blood-forming stem cell traveled through the body of a mouse. They saw that the cell multiplied and its progeny settled in the bone marrow and spleen. From studies of 113 mice, they learned that stem cells take their own sweet time moving into their permanent homes.

Taking the scenic route

It's no surprise that the stem cell's progeny reached the bone marrow and spleen. But the circuitous route they traveled to get to there was a shock. The cells took six weeks to fully inhabit all the available homes within those locations.

Rather than heading directly to vertebrae or ribs, where most bone marrow cells reside, the transplanted cells meandered. A population thriving in the shinbone might fade over time while their progeny set up camp in the distant skull. Or a population languishing in the spleen might suddenly flourish. When the researchers took stem cells from sites within one transplanted animal and put them into a second mouse lacking bone marrow, those stem cells once again seemed to take a random path to new niches, starting the game of musical chairs all over again. "This shows that the niche preferences aren't pre-programmed into the cells," says Christopher Contag, PhD, an assistant professor of pediatrics, radiology, and microbiology and immunology who led the study.

"We are really curious about what is happening," says Yu-An Cao, PhD, a research associate and first author of the study, published Dec. 15, 2003, in the online edition of the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. "We want to know why the process is so dynamic. There's no obvious reason for the stem cells to leave what appears to be a perfectly good place to homestead and proliferate."

Of all the locations, the spleen and the vertebrae were the two most likely sites for the new cells to settle. These are also the two roomiest compartments, according to Contag.

Where the cells go initially seems to relate to the size of the compartment and its openness," he says. If that location contained existing stem cells, the transplanted stem cell would likely detect signals indicating "this compartment is full, we don't want you here," he adds. An empty compartment probably lacks these unwelcoming signals. "The cells know there's an empty seat to jump into, and now we can watch them play musical chairs -- we just don't hear the music yet."

What's needed to track stem cells are markers that make them stand out, the equivalent of radio tags affixed to migratory birds. A decade ago Contag -- along with David Benaron, MD, associate professor of pediatrics; researcher Pamela Contag, PhD; and David K. Stevenson, MD, professor of pediatrics -- devised just such a cellular beacon and a device to view those glowing cells through an animal's body. The beacon is a firefly protein that was transferred into the stem cells before transplantation. This protein, called luciferase, produces a dim light when it contacts another molecule, called luciferin. Unlike fireflies, mice don't normally make luciferin, but the recipient mice were given doses of the molecule. Once injected into the recipient mice, the luciferase-producing transplanted stem cells and their progeny emitted a faint glow. Like a campfire at a new settlement, this dim light pinpointed the cells' location.

Although the light from small numbers of cells producing luciferase isn't bright enough to see by eye, the ultrasensitive video camera system developed by Contag and his collaborators can detect the faint light and show researchers where the glowing cells have settled. The experiment highlighted a handful of stem cell resting places, including the spleen and the bone marrow of the shinbone, thighbone, vertebrae, ribs, sternum and skull, where stem cells were already known to produce new blood cells.

Co-author Amy Wagers, PhD, is interested in improving the success of bone marrow transplants for cancer patients. She says the next step is to coerce the transplanted cells to populate the bone marrow more quickly. Contag's cellular tracking system could help with this, says Wagers, now an assistant professor at Harvard, who took part in the project as a Stanford postdoctoral scholar.

In addition to her efforts to speed the marrow's rebuilding, she's exploring another therapeutic avenue: tracking transplanted stem cells that have begun developing into immune cells. If these go to the right places, they might protect a person from infection until a new bone marrow is established.

Eventually, the work also could help guide transplantation procedures using other types of stem cells. Cao says an upcoming experiment will use the same technique to monitor transplanted neuronal stem cells. The findings could speed development of stem cell transplantation therapies for diseases of the nerve tissue, such as Parkinson's and Alzheimer's.

No matter what the disease, the challenge is convincing the wandering stem cells that coming home is the best part of traveling.

Christopher Contag and Pamela Contag are founders of Xenogen Corp., which commercializes the imaging technologies and now makes the video cameras that were used in this study.

Comments? Contact Stanford Medicine at