Short Take

|

|

Scientists reveal how a living cell holds on to its memories

By Rosanne Spector

Illustrations by Jeffrey Fisher

Our cells have memories — and good thing that they do. Without their ability to turn a fleeting chemical signal into a permanent memory, we’d never have made it past conception. A cell’s memory assures, among other things, that once it matures into an egg it won’t unexpectedly revert back.

So how does a cell manage to hold fast to a chemical message, long after the messenger has gone?

Last fall, two Stanford researchers showed for the first time how a living cell retains a memory. Along the way, they confirmed a theory proposed 42 years ago in France by Nobel prize-winning molecular biologists François Jacob and Jacques Monod.

“These very smart molecular biologists came up with a grand hypothesis on how cells of all kinds can take a transient stimulus and convert it into a permanent memory, but they didn’t have the tools to test it then,” says James Ferrell Jr., MD, PhD, professor of molecular pharmacology, one of the two researchers.

Decades later, with necessary tools in the form of modern biochemical techniques, Ferrell and Stanford postdoctoral scholar Wen Xiong, PhD, (now at UC-San Diego) put the theory to the test in the cell they were most familiar with: the frog egg. They published their experiments in the Nov. 27, 2003, issue of Nature.

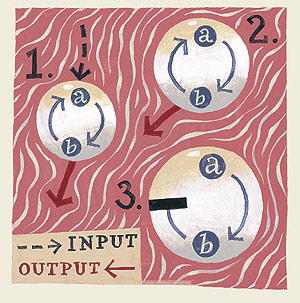

The theory points to the existence of simple positive feedback loops that allow a cell to “remember” it had received a particular stimulus once upon a time. For example, once a chemical stimulus would activate protein “A,” that protein would turn on protein “B,” which would circle back and promote the activity of protein “A,” thereby creating a positive feedback loop. This self-perpetuating loop would allow the cell to remember the initial stimulus that set it into motion, even after that stimulus had ceased.

In effect, the chemical stimulus flicks on a switch; the positive feedback loop prevents that switch from toggling back to the “off” position.

Message to cell: forget about it

To test the theory that feedback loops can serve as memory modules, Ferrell and Xiong took several steps. First they showed that a positive feedback loop was involved in the development of oocytes into frog eggs. “That part wasn’t too hard, at least in theory,” says Ferrell. “We incubated oocytes with their maturation stimulus, progesterone, and showed that the proteins in the feedback loop stayed activated for days after the progesterone was washed away.”

|

|

Figuring out how to wash the oocytes free of progesterone, however, was easier said than done. “That proved to be mindbogglingly aggravating, tedious, mundane work,” says Ferrell. “But it was what Wen had to do to get an interesting answer to an interesting question.”

Next, they wondered whether positive feedback was really required for this permanent response. Would the eggs

“Demature” if the loop was blocked?

The researchers came up with several ways to block the feedback from protein “B” (really a protein called MAP kinase) to protein “A” (actually, it’s called Mos), without interfering with “A’s” ability to activate “B.” In these experiments, when they added a feedback blocker and took away the maturation stimulus, they found the cell lost its memory: “B” promptly switched off.

As a result, the interactions among the proteins in this particular circuit changed, indicating that the cells had reverted to their immature state. The cells themselves, however, appeared to be dying. Normal frog oocytes look like tiny billiard balls, with one hemisphere grey, the other brown, and a white stripe running between. Mature eggs gain a white dot on top.

But these cells turned into grey puffballs, a sign they were on their way out.

"So, we have not found the fountain of youth,” Ferrell says. “There seems to be more than this one positive feedback loop that maintains eggs in a mature state.”

Ferrell and Xiong are not the only contemporary scientists to explore Jacob and Monod’s theory but they’re the first to show that it occurs in nature.

Brandeis University professor John Lisman, PhD, proposed a similar idea involving a different set of proteins, describing it in a theoretical paper in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences in 1985. But experiments have not borne out that particular notion.

And then in 2000 Boston University professor James Collins, PhD, described in Nature how he genetically engineered a “toggle” type memory circuit into the bacterium E. coli. “So that was certainly proof-of-principle for Monod and Jacob’s ideas anyway,” says Ferrell.

Xiong says she believes further studies will show that this is the major mechanism for creating a memory in cells. “However, it might not be the only one,” she adds.

What would the two Frenchmen say about Xiong and Ferrell’s experiment? “I don’t know,” says Ferrell. “But probably that it was magnifique!”

Their intellectual offspring, including Lisman and Collins, seem to think so at least — as Ferrell and Xiong have discovered by way of beaucoup congratulatory e-mails.

The research was funded by the National Institutes of Health.

Comments? Contact Stanford Medicine at