|

|

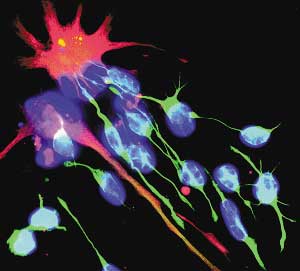

Cells with aptitude: Weissman's past work has shown stem cells from the brain can form many types of cells. They became neurons (green) and astrocytes (red). The blue stain indicates cell nuclei. |

|

Focus on the Stem Cell

By Ruthann Richter

Photograph by Nobuko Uchida

A School of Medicine announcement Dec. 10 that it would establish an Institute for Cancer/Stem Cell Biology and Medicine reignited national debate about stem cell research. The institute aims to harness the power of stem cell biology and Stanford's cancer research prowess to develop treatments for cancer and other genetically determined diseases. An anonymous donor has committed $12 million to launch the institute, which will be directed by stem cell researcher Irving Weissman, MD, professor of pathology and of developmental biology. "There's a remarkable confluence between what's happening in cancer cell biology and stem cell biology that might lead to new insights in terms of basic science, clinical application and prevention," says Philip Pizzo, MD, a cancer researcher and dean of the School of Medicine. Like cancer cells, but unlike most others, stem cells can divide indefinitely. Scientists at the new institute will explore similarities in how stem cells and cancer cells grow and multiply. The goal is to develop cancer therapies, possibly using stem cells themselves in the treatment, Weissman says.

Institute scientists also will work to create a new series of pluripotent (also called embryonic) stem cell lines to model cancer and other illnesses with genetic origins. Since a pluripotent stem cell can give rise to virtually any tissue in the organism, such cell lines offer a way to study a disease's influence throughout the body.

One method the institute might use to produce these cell lines caught the media's attention and sparked debate. Called nuclear transplantation, this approach is the first step in reproductive cloning -- the use of cloning to create a fully developed organism.

The procedure transfers a nucleus to an egg that has had its own nucleus removed. The cell divides seven or eight times to form a cluster called a blastocyst. The researchers remove cells from the blastocyst, and these cells go on to become the pluripotent stem cell line.

The other method involves inserting a nucleus carrying the DNA of interest into a cell from an existing stem cell line. The institute will investigate both techniques -- at first in mice.

Initial news coverage of the institute provoked a media frenzy when a wire service report incorrectly suggested Stanford was engaged in reproductive cloning, or the use of a blastocyst to produce a child. Pizzo made it clear the school will not be involved in this practice, which he termed "ethically unacceptable."

Later, editorials in newspapers around the country, including the San Francisco Chronicle and the San Jose Mercury News, expressed support for the institute's work. Pizzo says the school also received many messages of support from alumni, community members and researchers from other institutions.

The announcement of the institute triggered an angry response from Leon Kass, MD, PhD, chair of the Bush administration's President's Council on Bioethics. In a letter to university President John Hennessy, Kass noted that the council had enacted a four-year moratorium on nuclear transfer until there had been "vigorous public debate" and regulatory limits in place to prevent abuse.

In contrast, such research is encouraged in California under a new law, authored by state Sen. Deborah Ortiz, who says Stanford's work is precisely the kind of effort she hoped to promote.

Comments? Contact Stanford Medicine at