|

|

An unusual path to motherhood brings joy to a cancer survivor

By Ruthann Richter

illustration by Paul Wearing

photographs by Bryce Duffy

In February 2002, Gail and Bill Murray came to a Stanford University Medical Center laboratory to collect a precious piece of cargo -- 14 of their embryos frozen 2 1/2 years before, nestled in a bath of liquid nitrogen and stored inside a metal canister. They gently ferried the padded tank to the car and strapped it in, literally carrying their hopes for future progeny to a private clinic in San Francisco. There, eight of the embryos were thawed and three of the most viable-looking candidates were implanted in Gail's 25-year-old niece.

Today, Gail, who endured months of painful treatment for uterine cancer shortly after the embryos were frozen, is the mother of a baby boy. It is a sweet counterpoint to that dark period in 1999 when she grieved over her cancer diagnosis and the childless future it implied.

"It was not the cancer so much as knowing that I could not have children. That was the worst for me," says Gail, who is 41. "I knew I could beat the cancer. But not having a child was life-changing. I really wanted a biological child."

Fortunately, she had the foresight to preserve her childbearing potential by taking advantage of an unusual Stanford program that offers cancer patients -- whose fertility may be compromised by chemotherapy or other treatment -- the opportunity to freeze their eggs, embryos or ovarian tissue, essentially preserving their genetic potential for posterity. There are no more than 10 programs of this kind in the country, only a few of which are based at academic medical centers.

Since the Stanford program was begun in February 1999, 10 patients have had their eggs retrieved from their ovaries, frozen in suspended animation and then stored in the in vitro fertilization laboratory. Another 20 patients have had their eggs retrieved and fertilized by a husband or partner in the laboratory, then frozen at the embryonic stage for possible future implantation, says Lynn Westphal, MD, assistant professor of obstetrics and gynecology and director of the medical center's oocyte donor program.

Two pregnancies have resulted thus far from the program. One woman who had suffered from leukemia froze embryos before she received a bone marrow transplant. She gave birth in 2001, says Amin Milki, MD, associate professor of obstetrics and gynecology and medical director of Stanford's in vitro fertilization program. The second pregnancy to result from the program is that of Gail Murray's niece.

The Division of Reproductive Endocrinology and Infertility recently has considered extending the program to healthy women who see their fertility slipping out of reach and want to preserve their childbearing options, says Linda Giudice, MD, PhD, a professor of obstetrics and gynecology and the division chief. Though there is clearly public demand for such a service, it raises a host of ethical issues that are still under debate within the division and in the country at large [see sidebar]. And there is some reluctance to open the service to a broad population of women, as the science behind freezing of eggs and ovarian tissue is still in its infancy and the practice remains in the realm of experimentation.

While the freezing of embryos is routine and well-established, it's more technically challenging to effectively freeze, thaw and fertilize an egg to produce a viable pregnancy, says Barry Behr, PhD, assistant professor of gynecology and obstetrics and director of the IVF and Assisted Reproductive Technologies Laboratory at Stanford. Worldwide there have been fewer than 200 babies born as a result of egg freezing, about half of them in Italy, Behr says. No babies, whether human, mouse or other species, have ever been produced from frozen ovarian tissue, though recent studies from Stanford and elsewhere suggest the potential is there.

Egg freezing wasn't even considered an option until the mid-1990s, when scientists developed the intracytoplasmic sperm injection technique, known as ICSI. One side effect of freezing an egg is that it can alter the outer shell, making it nearly impossible for sperm to penetrate. ICSI overcame this obstacle, allowing embryologists to accomplish fertilization by injecting the sperm through the shell and directly into the cytoplasm, the central activity center of the egg.

|

|

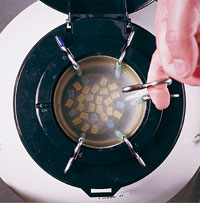

Fertility preserved: Eggs frozen in a liquid-nitrogen-filled tank. |

|

But other technical issues remain. The egg, which consists of a single cell, is highly vulnerable to injury during freezing, Behr says. Freezing works best when the cell is immature, at a stage when all of its chromosomes are tightly packed inside the nucleus and protected from damage. However, once the egg is thawed, it's difficult to coax it to continue maturing to the stage at which it would be primed for fertilization, he says. On the other hand, freezing the cell at a mature stage is more likely to cause damage to the egg, as the chromosomes are more vulnerable, spread out like a web of fragile threads.

"If we could learn to mature the egg in vitro, we would have a better grip on egg-freezing," Behr says. "Then they would survive better and be able to mature in vitro. Then we could add the sperm a few days later."

Behr, whose interest in egg freezing dates back to the mid-1980s, has been experimenting with chemical solutions that might help eggs better survive the freezing process. During his graduate school days at the University of Nevada, he studied the traits of polar animals that froze solid in winter and then thawed in summer to reproduce and function normally. He examined their blood and body fluids and found high concentrations of a particular sugar and amino acid. He then prepared a number of recipes with these ingredients and used them to try to freeze some 2,000 mouse eggs. His attempts were unsuccessful. But he must have been onto something: A recent cover of Fertility and Sterility, a highly respected journal in the field, featured an article showing that injecting this particular sugar into human eggs improved their survival rates after freezing. Behr is now planning to test different media -- combinations of various nutrients -- to fortify human eggs before freezing to help ensure their viability.

While use of frozen eggs is far from general clinical application, use of frozen ovarian tissue is further still. In theory, women whose ovaries are removed because of cancer, endometriosis, trauma or other conditions could have some of this tissue frozen, then later thawed and stimulated to produce eggs, which could be used as the seed for a child. In September 2001, researchers at Cornell University reported some success with this approach in two cancer patients, both women in their 30s. The researchers removed the women's ovaries, froze the ovarian tissue in strips and later thawed and implanted it under the skin of the women's forearms. They selected the forearm for implantation because it has a good blood supply and offers easy access. The researchers were able to induce the grafted tissue into producing egg follicles, although attempts to fertilize the eggs were unsuccessful, the group reported in the Journal of the American Medical Association.

|

|

Bill and Gail Murray at home with Kristin (center). |

|

A Stanford team recently performed similar experiments in mice, with good results. The group removed the ovaries of the mice, sliced the organs into strips, froze the tissue and thawed it five days later. They primed the mice with gonadotropins -- hormones that stimulate egg production -- and then grafted this tissue under the skin on the flanks of the animals. The implanted ovaries produced eggs, which were effectively fertilized in the laboratory to create embryos, the team reported in August 2002 in the Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. Those eggs derived from animals and primed with hormones fared better than those that didn't get this extra boost, a finding that ultimately could be useful in human applications, Behr says.

"We don't have babies yet in the mice, but it worked. The eggs fertilized and began to develop. More importantly, the mice produce hormones, and they cycle like normal mice," says Mary Lake Polan, MD, PhD, professor and chair of the Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology. Polan was one of the investigators on the study, which included Hongbo Wang, MD; Stephen Mooney, MD; Yan Wen, MD; and Behr.

Some cancer patients participating in the egg-freezing program also have opted to have ovarian tissue frozen, in the eventuality that these techniques someday prove to work in humans.

|

|

Lynn Westphal, MD, (left) and Barry Behr, PhD, at the IVF clinic. |

|

"For those patients, there is no downside (to ovarian tissue freezing)," Westphal says. "Instead of taking all of the tissue to pathology, we will freeze part of it in the hopes that it will be useful down the road."

Gail Murray chose to have some ovarian tissue frozen along with her 14 fertilized eggs. Like many women who receive a cancer diagnosis, fertility preservation was not the first concern that rose to her mind, and she was only vaguely aware that such an option even existed.

"When I was first told about the cancer, I was hysterical. I went home and Bill and I cried for days," she says. "Then we decided we weren't going to cry anymore. We needed to be positive. We needed to focus on being better."

Gail and Bill had been together for several years and had already made a life plan that included children. Gail asked her doctor whether there was any way to preserve her childbearing potential. She referred her to Westphal, who moved her quickly through the process, as her cancer was well-advanced.

In the weeks that followed, Gail gave herself a series of daily hormone injections to spur her ovaries to generate as many eggs as possible. Then she had the eggs retrieved during a 15-minute procedure at Stanford. The clinicians used a small needle inserted into the vagina to reach Gail's ovaries and gather her eggs. Then they aspirated out the follicles. Gail had 21 eggs retrieved; 14 of the best candidates were fertilized and frozen at the zygote stage. She says the process gave her a positive focus at a time of great emotional strain.

"You actually have no control over the cancer, but I had control over the egg retrieval," she says. "It was my decision to do the IVF. It was my decision to have the baby. The cancer was secondary. Having the baby was the primary thing."

Gail had a hysterectomy in the fall of 1999, followed by a series of enormously painful radiation therapy treatments. She has been cancer-free since then. She and Bill gave no serious consideration to having a child until last winter, when her niece, Kristen, who lives near Sacramento, came forward and offered to serve as a surrogate. Gail was surprised, thrilled and enormously grateful, she says.

After Kristen became pregnant, Gail followed the baby's progress via ultrasound. The images showed that the fetus was developing normally.

"With the embryo being frozen for almost three years, I was thinking science fiction," Gail says. "It's like 'The X-Files.' Is this baby going to have 10 fingers? I could see on the ultrasound that he's normal. I could see his hands, his eyes, this little thumb go in his mouth. The legs, the torso, the spine, it was all there. I thought, 'Phew, he's got all his parts.' "

Freezing and thawing do not appear to cause chromosomal damage, says Westphal, who notes that there has been no reported increase in birth defects among children born from frozen eggs or embryos.

Gail's son was born Dec. 21, 2002, "a beautiful, healthy boy," 8 pounds 1 ounce and 21 inches long, she says. "What a wonderful Christmas present. We are very excited and very happy to finally be parents."

Reproductive Discussions: Consider offering the potential of putting motherhood on ice

The world of reproductive technology is fraught with ethical quandaries, and the practices of egg and embryo freezing are no exceptions. Some of these ethical questions have come to the fore in recent months as the Division of Reproductive Endocrinology and Infertility considers offering healthy women the opportunity to preserve their genetic potential by having their eggs or ovarian tissue preserved in cold storage for possible future use. Research suggests that human eggs can be frozen indefinitely, as all biological activity ceases when freezing occurs, says Barry Behr, PhD, assistant professor of obstetrics and gynecology and director of the In Vitro Fertilization and Assisted Reproductive Technologies laboratory at Stanford.

In theory, a woman in her 20s, say a medical student who has years of training ahead of her and wants to postpone motherhood, could choose to have her eggs frozen and thawed years later for implantation, Behr notes. However, "We don't have data on how long eggs can be stored, so there is no guarantee those eggs will be viable 15 years from now," he says. In the meantime, the young medical student, investing her hopes in egg freezing, might have passed on the prospect of pregnancy during her most fertile years.

There's also the issue of whether scientists should make use of available technology to encourage women to delay childbearing until much later in life, says Linda Giudice, MD, PhD, professor of obstetrics and gynecology and the division chief. "It really starts the discussion going down a slippery slope if one is going to offer something that allows women to delay childbearing as long as they want to," Giudice says.

While there are concerns about the risks -- both to mother and child -- when older women give birth, one recent study suggests these risks may be relatively small. The study, published Nov. 13, 2002, in the Journal of the American Medical Association, found that women over age 50 who conceived with donor eggs gave birth to normal babies. While the women had a higher incidence of hypertension and diabetes, they did reasonably well during the pregnancy, the study found.

Clearly, the demand for tissue preservation is there. Behr says he receives about a call a week from women, particularly in their mid- and late 30s, who see their fertility slipping away and want to keep their options open. Heidi Flaherty, a 40-year-old Mountain View, Calif., resident is typical of those callers. A single, successful career woman, she is unprepared to have a child on her own but is still keen on keeping the door ajar on the prospect of being a mother someday.

"At least I can say I gave it every shot," says Flaherty, a chief financial officer for a local technology firm. "If it's not meant to be, it's not meant to be. Or conversely, if it's meant to be, it's meant to be... . But a little bit of an option is better than no option. I don't want to get into a situation where it's no option for me."

With demand from women like Flaherty, private clinics have begun to commercialize the business of egg-freezing -- a trend that Behr and others find troubling, as these clinics have no oversight, accountability or good science behind them, he says. If Stanford were to offer the service to healthy women, it would do so in the context of an experimental protocol, with institutional review board consent and the goal of advancing the science of egg freezing, he says.

Stanford already has taken pre-emptive measures to avoid some of the ethically thorny situations that have arisen elsewhere in the country, where families of deceased cancer patients have fought for custody of a patient's preserved tissue or opted to have it implanted in a surviving relative or other surrogate. In the current protocol for cancer patients, the women must specify in advance whether their eggs should be discarded or dedicated to medical research in the event of their death. In the case of human embryos, both partners must specify their collective wishes in writing at the time of freezing.

Faced with increasing societal pressures, the American Society for Reproductive Medicine recently formed a task force to look at issues surrounding egg cryopreservation, including who should provide such services, what patients should be eligible, what oversights should be in place and the ethical issues involved, says Giudice, an ASRM board member. At Stanford, the Division of Reproductive Endocrinology and Infertility has convened its own ethics board, including a university ethicist and a lawyer, to help address these questions, she says.

Comments? Contact Stanford Medicine at