What’s behind the controversy over screening and treating

By Mitzi Baker

Illustrations by Jeffrey Fisher

Photography by Leslie Williamson

|

|

The prostate is a small organ wrapped in a great big controversy. The walnut-sized organ, responsible for producing the fluid in which sperm travel, has a very high probability of turning cancerous – for some as-yet unexplained reason. The only quantitative test for the presence of prostate cancer is riddled with inconsistency and, except in cases of extreme malignancy, gives no indication of the cancer’s severity. All current treatment options have significant shortcomings so the decision about which route to pursue can be daunting. Men might well question whether to get tested or treated at all for a cancer that is usually slow growing and that they are more likely to die with than of. Even the experts often disagree on when to test and when to treat.

To understand the controversy and confusion surrounding testing and treatment – and why the best treatment might sometimes be no treatment at all – is to begin to appreciate the enigmatic disease that is prostate cancer. “There are a lot of unique things about this organ,” says associate professor of urology Donna Peehl, PhD. “We don’t understand how any of those unique things might really be linked to why cancer is so frequent in the prostate.” Likely explanations include the prostate’s dependency on testosterone, the type of cells it is composed of and its heightened sensitivity to certain carcinogens. But at this time, says Peehl, “We are at square one here.”

What is known is that the prostate develops tumors more frequently than other organs. Luckily these tend to be much more slow growing than other tumors, which means that a man could live years with prostate cancer and end up dying of another cause. The sluggishness of the tumor growth and the small tumors’ low probability of migrating to other parts of the body make prostate cancer controversial to treat, especially since the gold standard for treatment – complete removal of the prostate – can leave a man impotent and/or incontinent.

While the treatment can be worse than the disease itself, prostate cancer remains a leading cause of cancer death, fifth in overall causes of death, killing around 30,000 men in the United States per year. “As much worry and hand-wringing as there is about whether we should be screening and whether we should be treating, I always remind people, it is still the second-leading cancer killer in men,” says assistant professor of urology James Brooks, MD. “This is not a trivial cancer.”

However, urology professor Thomas Stamey, MD, emphasizes that one of the unique aspects of this disease is its ubiquity. He contends that every man will develop some cancer in his prostate if he lives long enough, but a very small percentage of those tumors will progress to a life-threatening form. He says that while it is second only to lung cancer as the most deadly type of cancer for men, prostate cancer has a very different profile.

“I don’t believe it’s fair to compare prostate cancer to lung cancer,” says Stamey. “Almost every man diagnosed with lung cancer dies of lung cancer, but only 226 out of every 100,000 men over the age of 65 die of prostate cancer,” he says, citing data collected by the National Cancer Institute.

Regardless of the controversy about whether to test and treat prostate cancer, the fact remains that some tumors that are unidentified and/or left untreated can migrate to other parts of the body, at which stage they are virtually untreatable. How to identify those invasive tumors is one of a number of mysteries that remain to be solved.

|

|

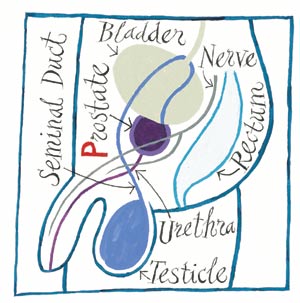

It's surrounded – by the bladder, rectum and urethra.The prostate is encircled by tissues and nerves easily damaged during surgery – damage that can lead to impotence and incontinence. |

|

Fortunately, every scientist loves to solve a good mystery, so prostate cancer has lured a team at Stanford to hunt for clues from start to finish – from why it arises to how to best recover from prostate removal. The researchers, clinicians and surgeons looking at this disease are concentrated in the Department of Urology, but researchers from the Department of Radiation Oncology and the oncology division of the Department of Medicine also study prostate cancer. “Because it is such a common cancer, there are a lot of people interested in it,” says Brooks. “That interest piques a lot of controversy.”

Some of the work being done at Stanford might eventually quench the fire of controversy as the mysteries give way to an understanding of the disease. These researchers are particularly interested in how to tell definitively if cancer is present and, if so, to tell how serious it is. “One of our strengths is the detection work that we are doing. I think that is something that patients are specifically coming to Stanford for,” says associate professor of urology Joseph Presti Jr., MD. “This work is clinically relevant to the patient as well as research-related. We know that early detection translates to improved survival.”

Testing for Prostate Cancer

“The fact that the annual death rate from prostate cancer has dropped from 44,000 about 10 years ago to about 30,000 now, shows that we are probably doing something right by screening men pretty aggressively,” says Brooks. He is referring to the widespread testing of men using the controversial PSA test. PSA is short for prostate specific antigen, a protein secreted by the prostate into the ejaculatory fluid to keep semen liquid; a cancerous prostate tends to produce more PSA. Some PSA makes its way into the bloodstream, so high levels there can indicate a prostate problem.

Although it sounds like a straightforward check of prostate health, the PSA test is plagued with inconsistencies. About 20 percent of men with prostate cancer never develop high levels of PSA, while more than two-thirds of men testing high will turn out to be cancer-free. A number of conditions other than cancer can increase the PSA level, including infection, inflammation and benign tumors.

While the standard advice to men is an annual PSA test after the age of 50 (earlier if there is a family history of prostate cancer), some question this recommendation; the Centers for Disease Control does not recommend routine screening for prostate cancer because there is no scientific consensus on whether screening and treatment of early-stage prostate cancer reduces mortality.

|

|

Donna Peehl, PhD, associate professor of urology. |

|

Stamey published the findings in 1987 in the New England Journal of Medicine indicating that blood PSA levels could be used to indicate prostate cancer. However, through the years, Stamey has come to believe that the PSA test is actually not a useful predictor of the amount or severity of prostate cancer. Through careful comparison of prostate pathology and PSA levels in 875 men undergoing prostate removal surgery, he has found that until the PSA level becomes very high, it is not useful in predicting cure rates following prostate removal. He published these conclusions in the Journal of Urology in 2002.

Stamey claims that equating elevated PSA levels with prostate cancer is causing over-diagnosis and over-treatment of the disease. High PSA levels are frequently due to a harmless increase in prostate size known as benign prostatic hyperplasia. “All you need is an excuse to biopsy the prostate and you are going to find cancer. It’s a disease all men get if we live long enough,” he says. “I’m a part of that problem; I wrote the first paper showing that the level of PSA correlated with how much prostate cancer you had.”

But do the conclusions from Stamey’s 2002 study apply to the general population of men? Brooks says they might not. He points out that the subjects in that study all had prostate problems that brought them to their doctors. Although some of the men had low PSA readings but nonetheless had palpable prostate tumors, Brooks says that PSA should not be discounted as a useful screening tool. He says that, in fact, the PSA test has proved itself to be a better cancer screening tool than mammography. “The bottom line is that if you use rises in PSA as a tool for picking up cancer [in the general population], it’s pretty good. It works pretty well,” he says. Presti concurs. “The PSA test has revolutionized detection,” he says. “It may not be perfect, but it’s the best we’ve got.”

Beyond the PSA Test

That the PSA test is less than ideal and a better screen is needed is just about the only consensus in the arena of prostate cancer detection. “I think that PSA has been proven to be a reasonable screening tool, but not definitive, and I want those definitive answers,” says Brooks. “Sure, we need a better tool and we’re all doing research to find better tools.”

Stamey agrees, adding that what would be ideal is some sort of indicator, preferably one that occurs in the blood, that would not only indicate if cancer was present but also how malignant it was. “The only way we are going to stop the overkill for prostate cancer is to find an honest-to-goodness marker that is proportional to the amount of cancer,” says Stamey. “Since all men get the cancer, the marker has got to be proportional to the amount.”

To assist them in finding some proteins that will constitute a new marker, several of the Stanford investigators are taking advantage of the latest in DNA microarray technology, which allows them to look for changes in thousands of genes in a single experiment. They can compare normal prostate cells with those in various stages of malignancy and then try to link any genetic changes with diagnostic clues, such as variation in how the cells look. Stamey’s group is completing a survey of 25,000 prostate cancer genes looking for a new detection marker.

Brooks’ group, along with the lab of biochemistry professor Pat Brown, MD, PhD, is also using microarrays to look at what genes are turned on and off in prostate cancer. They have preliminary findings showing that there are three molecular subtypes of prostate cancer based on what groups of genes are turned on and off. The subtypes also appear to coincide with the behavior of the tumors; one indicates an aggressive form, one an intermediate form and one much less aggressive. This information might eventually provide markers that would indicate the subtype present, which could help determine whether invasive treatment is warranted.

The Next Steps

Currently, if a patient opts for a PSA test and discovers his level is high, the next step is the biopsy: removing small pieces of the prostate with a tiny needle to look for microscopic abnormalities in the cells. Presti, who is the director of the Genitourinary Oncology Program, says that a prostate is never removed or treated based solely on an elevated PSA or a lump felt during examination.

|

|

Joseph Presti Jr., MD, associate professor of urology. |

|

Presti has been investigating the benefit of sampling eight to 12 locations – rather than the traditional six – and has improved the biopsy technique so that it can be performed as an outpatient procedure. Previous methods required a general anesthetic and a hospital stay. He and senior research scientist John McNeal, MD, took 10 biopsies each from 185 patients previously receiving negative diagnoses and found 36 percent of them actually had prostate cancer after all. The researchers took extra samples in the region of the prostate most likely to turn malignant, which accounted for the increase in cancers found.

If biopsy samples reveal cancerous cells, a man and his physician then decide on the next step. If they choose prostate removal, the prostate itself is available for analysis. McNeal has devoted countless hours to developing a quantitative analysis of microscopic prostate tissue slices to improve the accuracy of diagnosis and of the prognosis following prostate removal.

They are looking for the abnormalities that take place in prostate cells during the progression to cancer. “I think that most of the changes that lead to cancer take place in the pre-malignant stage. Prostate cells have a wide variety of interesting histologic patterns. Invasive cancers tend to be free spirits: They sort of look like anything, go anywhere, but dysplasias [pre-cancers] have definite patterns,” says McNeal. “I think it is going to be possible to classify those patterns and associate them with the type of genetic abnormality that is taking place.

Biopsy shows only what is happening in a very small portion of the prostate, but it remains the most accurate available measure of the presence of cancer. The ability to better identify the early-stage cancers is critical to figuring out how aggressively to treat patients. McNeal says he hopes to change the diagnostic process with his careful microscopic examination of visible changes in the cells.

One way around the challenge of diagnosing and treating prostate cancer is to simplify the problem to its basics. To that end, Peehl is developing cell models to get to the bottom of why prostate cells are so unique. “The complexity of the prostate has slowed us down,” says Peehl. “I am hoping to figure out how to manipulate the cells and make them do what we want them to do.”

Brooks is optimistic about the future. “I think that within the next decade we are going to be able to make very discrete recommendations about prevention,” says Brooks. With regard to screening, he says chances are good that better markers will be available in the next decade. “That will reduce the number of biopsies men have to go through,” he says. And improved prognosis markers differentiating aggressive and non-aggressive forms of cancer will help tailor therapy.

But for now, such definitive answers about prostate cancer lie beyond our reach.

When it comes to treatment, new procedures reduce side effects

Men face a difficult decision when choosing whether to get treatment for prostate cancer. The multiplicity of treatments available adds to the decision’s complexity. A patient must choose among radiation and hormone therapies and various types of surgery. The standard course, surgical removal, is burdened by potential side effects of incontinence and/or impotence. But there’s good news. Improvements in treatments allow men to avoid these undesirable outcomes. Some of the new techniques for prostate cancer treatment at Stanford include:

Nerve-sparing surgery

The prostate is small, difficult to see and is buried deep in the pelvic region,

surrounded by the bladder, rectum and urethra. While removing the prostate

using the standard surgical method, surgeons can easily damage nerves and

delicate tissues, which can lead to permanent incontinence or impotence.

Assistant professor James Brooks, MD, and associate professors Joseph Presti

Jr., MD, and Harcharan Gill, MD, in the Department of Urology are performing

a more precise version of prostate removal – nerve-sparing radical

prostatectomy – which greatly reduces the chance of incontinence and

impotence.

Laparoscopic radical prostatectomy

Assistant professor of urology Thomas Hsu, MD, and Gill are providing a minimally

invasive variation of prostate surgery. Performed by inserting thin flexible

cameras and instruments through five small holes in the abdomen, this technique

is more challenging to perform than standard surgery. But it offers many

advantages, including less blood loss, less postoperative pain, a shorter

hospital stay, fewer days with a catheter and a quicker overall recovery.

CyberKnife

Assistant professor Chris King, MD, PhD, and professor Steve Hancock, MD, in

the Department of Radiation Oncology are adding to their prostate cancer

treatment arsenal with a radiosurgical machine, known as CyberKnife, that

uses high-energy X-rays to kill tumors. King and Hancock will be the first

to use CyberKnife for treating prostate cancer. CyberKnife precisely targets

large doses of radiation on the tumor.

Comments? Contact Stanford Medicine at