Mission: Translational

[The expression "translational medicine" sums up Stanford University Medical Center's top priority: translating the insights of students, clinicians and scientists into practical advances that enhance and prolong life.]

|

|

Michele Calos, PhD, has solved one of gene therapy’s major problems. |

|

Michele Calos has developed a technique that guides therapeutic genes to safe places on the chromosome

By Amy Adams

Photographs by Meredith Heuer

Illustration by Ian Worpole

Until recently, gene therapy faced a damned-if-you-do, damned-if-you-don’t

dilemma. In the safest form of gene therapy, a gene inserted into the

cell survives briefly and makes a necessary protein, but the gene eventually

breaks down and its therapeutic effect fizzles away. A longer-lasting

treatment involves wedging the gene into a chromosome, where its benefits — or

detriments — last indefinitely. The long-lasting effects would be

a therapeutic boon except for the collateral damage inflicted by the

gene as it inserts into the chromosome.

This problem came to a head in the fall of 2002, when the first successful

gene therapy trial turned sour. The trial, based at the Necker Hospital

for Sick Children in Paris, was for severe combined immunodeficiency,

or SCID — otherwise known as the “bubble boy” disease — in

which some immune cells don’t mature, leaving a child susceptible

to any infection that comes along. A gene inserted into cells of the

bone marrow stimulated new immune cells to form and cured nine of the

11 children in the trial. But then two of those children developed leukemia,

probably because when the therapeutic gene elbowed its way into a chromosome

it activated a neighboring leukemia-causing gene. That trial, and 27

other gene therapy trials for otherwise incurable diseases, abruptly

ended.

It was in this environment that Michele Calos, PhD, published papers

in Nature Medicine and Nature Biotechnology describing

a new gene therapy technique that avoids the pitfalls of older approaches.

Unlike therapies in which the gene survives only briefly, her approach

allows the gene to enter the chromosome, where its effect is long-lived.

And with Calos’ technique, the gene enters the chromosome only at

known genetic addresses, which so far seem nowhere near problematic genes.

“Ever since we released those papers I’ve had a continuous

flurry of e-mail,” says Calos, associate professor of genetics at

the School of Medicine. “The leukemia patients really put into focus

a basic flaw with current gene therapy techniques.”

The “aha” moment

The key to gene therapy is inserting a healthy copy of a gene into the

cells of a sick person, then hoping that gene will make a normal protein

to cure the disease. To pull off this feat, most researchers take advantage

of a retrovirus, a type of virus that inserts its genes into human DNA.

In gene therapy, researchers replace the disease-causing viral DNA with

their therapeutic gene, then let the virus do the hard part of integrating

the gene into a chromosome.

The problem is that the retrovirus is not very discriminating. Sometimes

it lands in a harmless location, but other times it damages its genetic

neighbors in the process of moving in. It’s this recklessness that

led to problems in the SCID trial.

While attempting to devise a better gene therapy technique, Calos noticed

a research article that seemed interesting enough to take home for a

careful read. “I read the paper that night and I literally put a

graduate student on that project the next day. I realized immediately

that it was exactly what we needed,” Calos says.

|

|

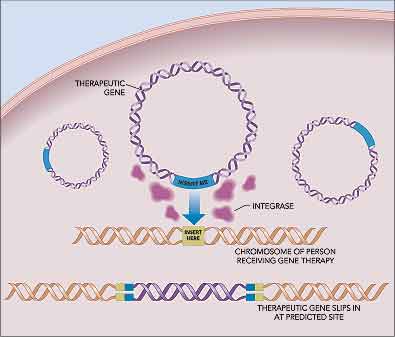

Goodbye guesswork: By guiding new genes to known locations, integrase turns gene therapy into more of an exact science. |

|

The paper described a protein called an integrase that inserts genes

into a precise location marked by a genetic “insert here” sequence

in the bacterial chromosome. It turns out that humans also have several

gene regions mimicking that sequence scattered throughout the genome.

Calos thought that if the integrase could recognize those pseudo-integration

sites in humans, she could create the first gene therapy technique that

guides the insertion of genes into human chromosomes.

“It’s one of those serendipitous things. Once we knew about

the integrase everything just fell into place and no huge roadblocks

came up,” Calos says.

Her technique has only two components — a therapeutic gene flanked

by an “insert me” sequence and the integrase. The integrase

inserts the therapeutic gene into one of several sites in the human genome;

then the integrase breaks down over the next few days leaving only the

inserted gene as evidence of its genetic tinkering.

Put theory into practice

Calos initially tested her approach using a gene that makes factor IX — a

protein missing in the blood of people with one form of hemophilia. She

and Mark Kay, MD, PhD, a Stanford genetics professor who specializes

in gene therapy techniques, injected mice with a piece of DNA containing

the factor IX gene. Within a week, mice that received this injection

had 12 times more factor IX in the blood than their littermates that

received the injection without the integrase. That’s enough factor

IX to treat a person with hemophilia.

In addition to working on hemophilia, Calos has responded to the worldwide

interest in her approach by joining forces with researchers studying

more than a dozen different diseases. “A lot of people working with

retrovirus need a solution, so they are trying to switch over to integrase,” Calos

says. The collaborations haven’t left Calos pining for the quiet

days of yestermonth. “This is so much more fun with more people

involved,” she says.

Teaming up

One of her collaborators is Paul Khavari, MD, PhD, who did the initial

work with human skin cells. She and Khavari were working with skin cells

from patients with a disabling disease called recessive dystrophic epidermolysis

bullosa, in which the outer layer of skin separates too easily from the

underlying layers. Children with the disease have severe blistering,

scarring, infections, and they often die young.

She and Khavari, a Stanford professor of dermatology, injected a healthy

copy of the gene that’s mutated in epidermolysis bullosa into skin

cells taken from children with the disease. They then allowed those cells

to multiply in a lab dish and placed them on the skin of a mouse. Once

in place, those cells formed normal skin and made a normal copy of the

protein that located to the appropriate place in the skin cells.

Another Stanford collaborator of Calos’ is Thomas Rando, MD, PhD,

who works on muscular dystrophy — a disease that cries out for gene

therapy, according to Rando. “The only treatment for any form of

muscular dystrophy is very unsatisfactory,” he says. Because the

most common form of the disease is caused by a mutation in a single gene,

it is a perfect candidate for gene therapy.

The integrase gene therapy offers an added bonus for treating muscular

dystrophy. The gene that’s most commonly mutated in this disease,

called dystrophin, is too large to fit within the narrow confines of

most viruses. Because Calos’ technique does away with stuffing genes

into viral containers, researchers can inject the genetic behemoth into

cells with a reasonable hope of it integrating into human chromosomes.

This same advantage holds true for treating cystic fibrosis and epidermolysis

bullosa, both of which are caused by mutations in large genes.

The problem for gene therapy in muscular dystrophy is one of delivery,

says Rando, associate professor of neurology and neurological sciences

and director of the muscular dystrophy clinic. “Muscle is distributed

throughout the whole body. You have to get the gene to muscles ranging

from the leg to the heart to the diaphragm. It’s a major delivery

problem.”

Research with mice shows that a gene injected directly into muscle can

integrate into local cells, but a person with muscular dystrophy needs

more than a few square inches of treated muscle. One possible approach,

Rando says, is to inject dystrophin genes and integrase proteins into

an artery where the blood can then shuttle them throughout the body.

Rando and his colleagues are working on ways to keep the DNA intact and

able to enter muscle cells after it is injected into the blood.

From mice to men

Problems with gene delivery crop up any time a gene has to work its

way into a particular cell type. That’s one reason Calos expects

gene therapy for hemophilia to be her first project to make it to human

trials. In this blood disease it doesn’t matter what tissue contains

the therapeutic gene, as long as the protein winds its way into the blood

supply. Inserting a gene into either muscle or skin cells, both of which

Calos knows are compatible with her technique, has the potential to release

therapeutic proteins into the blood.

Though Calos’ current work is in animals or human cells, her goal

is to see her brainchild used to treat human patients. “You are

seeing the beginning of a new era in gene therapy for a bunch of diseases,” Calos

says. “My goal is to see this really used in medicine.”

Getting a therapy to human trials takes money, and money usually comes from pharmaceutical companies or private investors. So Calos and two colleagues have started a company to move her technique into the clinic. They named the company Poetic Genetics because, says Calos, like words in a poem the magic of gene therapy is to create a lasting impression. Poetic Genetics has begun the task of finding potential funders who aren’t scared off by either the limping economy or fears about gene therapy. A few investors meet both of those criteria, leaving Calos hopeful that through Poetic Genetics her technique will one day make a lasting impression on genetic diseases.

Comments? Contact Stanford Medicine at