|

|

Stanford caregivers thwart Marfan syndrome’s deadly course

By Krista Conger

Illustration by Philippe Lardy

Photographs by Meredith Heuer

Nancy Mateyka always knew she was different. Nearly 6 feet tall, she

towered over her fifth-grade classmates. But it wasn’t just her

unusual stature that convinced her there was something wrong.

“I used to joke that I looked like I swallowed a cardboard box,” she

says. “Even though I was tall and thin, I had no waistline. I’d see

other tall people, but they didn’t look like me.” The reason would

evade her for 26 years and took the life of her only sister.

Her sister’s death saved Mateyka’s life. Diagnosed at age

41 with Marfan syndrome, her sister died a year later of cardiac complications

that accompany the genetic disorder. Mateyka realized she shared the

same faulty DNA that causes Marfan syndrome.

Armed finally with a name for the condition, she sought help, first

from a cardiologist near her home in Chico, Calif., and then from Stanford’s

Center for Marfan Syndrome and Related Connective Tissue Disorders. There

she received the life-saving heart surgery her sister wasn’t lucky

enough to have.

Founded in 1988 by cardiovascular surgeon D. Craig Miller, MD, the center

is one of only about five other comprehensive centers in the nation specializing

in what is a surprisingly common disorder. The Stanford center brings

together an unprecedented number of physicians and disciplines to treat

every aspect of pediatric and adult Marfan cases. Miller is one of the

few surgeons in the world with extensive experience in repairing the

heart damage of Marfan syndrome without removing the patient’s own

aortic valve — freeing the patient from a lifetime of blood-thinning

medication. Mateyka was one of the first 20 patients to have the new

operation at Stanford Hospital.

A Stealthy Foe

It’s not unusual to discover one has Marfan syndrome only after

a family member dies from it.

Although Marfan syndrome affects about one in 5,000 people, many don’t

know they have the disorder. But if left undiagnosed, the first unmistakable

sign of Marfan syndrome is also often the last.

Marfan syndrome is caused by a genetic mutation that weakens the connective

tissues that hold the organs and bones in place in the body like beads

on an intricately decorated belt. Use elastic instead of leather, or

rubber in place of thread, and the pattern is easily stretched and distorted.

Bones grow longer, joints are looser and blood vessels are less resilient

than those made of standard-issue tissue.

The severity and number of physical symptoms can vary wildly, however,

making diagnosis tricky. People with Marfan syndrome are often tall,

with loose joints and disproportionately long arms, legs and fingers.

They may have long narrow faces with deeply set eyes, and sunken or protruding

chests. Many also experience lens dislocations in their eyes, which can

cause blindness. Although some people with Marfan syndrome are clearly

affected, the relatively mild signs exhibited by many sufferers like

Mateyka can be passed off as intriguing, but not alarming, quirks of

nature.

“It can be a very subtle diagnosis,” says cardiologist David

Liang, MD, PhD. “We can’t always tell with 100 percent certainty

after looking at a patient. Diagnosis still is a little bit of an art.” Because

an affected parent has a 50 percent chance of passing Marfan syndrome

to a child, Liang and other physicians at the center also consider a

patient’s family history when making their diagnosis. But a spotless

background doesn’t guarantee a clean bill of health: The mutations

that cause the syndrome can also arise spontaneously within a parent’s

egg or sperm.

As onerous as the external baggage of Marfan syndrome is — Mateyka

was teased so mercilessly that at age 11 she vowed never to have children

who might inherit her unusual height— the real danger lurks behind

the scenes, in the blood vessels that rely on elastic connective tissue

to allow them to absorb and dispel the heart’s rhythmic force.

Sprouting directly from the left ventricle of the heart like a sapling,

the ascending aorta is solely responsible for collecting and delivering

freshly oxygenated blood to every tissue in the body. Because it bears

the brunt of each heartbeat, it is at particular risk for failure in

Marfan syndrome. Three wispy pieces of tissue separating the aorta from

the heart form the aortic valve, a one-way gatekeeper that snaps together

after each heartbeat to block freshly expelled blood from rebounding

back into the heart. Together the ascending aorta and the aortic valve

are known as the aortic root.

When the connective tissue in the aortic root is not up to snuff, the

weakened aorta gradually balloons out under the pressure of the heart’s

pounding. The expansion, called an aneurysm, can pull the valve tissue

apart, allowing regurgitation of blood into heart and demanding ever

more work from the overtaxed left ventricle. It can also cause the inner

lining of the weakened aorta to tear, permitting blood to course within

the walls of the vessel like a moving blister. Eventually, the errant

blood either breaks back through the lining to rejoin the main current

or bursts through the outer lining in an aortic rupture.

Called an aortic dissection, the condition often comes with sudden,

severe chest pain that moves outward as the rushing blood charts new

territory. It can also cause confusion, pallor, a rapid pulse and a variety

of other contradictory symptoms.

“Acute aortic dissection is the great masquerader,” says Miller,

the Thelma and Henry Doelger Professor of Cardiovascular Surgery. “The

patient can experience pain in the chest or belly, cold legs or other

symptoms, depending on where the dissection ends. It can mimic almost

any other acute medical emergency.”

Unmasking marfan

The stakes for accurate diagnosis of aortic dissection are high; the

chances for survival decrease 1 percent every hour for the first 48 hours

in untreated patients. Half of the patients with a full-scale aortic

rupture will die. Unfortunately, Marfan syndrome patients tend to be

particularly hard to diagnose as they are often relatively young, with

no obvious cardiac risk factors to tip off clinicians. Mateyka’s

sister waited for nearly six hours in a Wisconsin emergency room before

her unusually long fingers helped a physician put two and two together.

“There is a lot of ignorance out there,” says Miller. “Patients

may have Marfan syndrome but are not recognized. When they go to the

emergency room with chest pains, they may be ignored.” His warning

is not just idle speculation: playwright Jonathan Larson, the creator

of Rent, died in 1996 of a ruptured aortic aneurysm after visiting two

New York emergency rooms complaining of chest pain. Physicians had dismissed

his complaints as food poisoning or a viral infection.

|

|

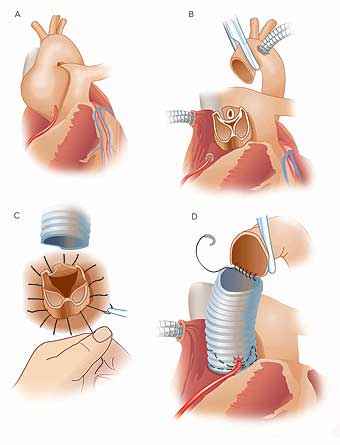

Valve-sparing aortic root repair. During valve-sparing aortic root replacement, the surgeon removes the aneurysm and the tissue surrounding the valve, including the right and left coronary arteries that supply blood to the heart (A and B). Sutures are used to attach a woven tube to the heart (C) and the valve is firmly anchored within the tube with another row of sutures (D). The coronary arteries are then reattached to the tube, and the top of the tube is connected to the loose end of the aorta (D). |

|

“Emergency physicians have told me in tears how they have lost

a person with Marfan syndrome or how a person with Marfan syndrome managed

to survive even though they didn’t know about the disorder,” says

Mateyka, who in 1999 manned a booth for the National Marfan Foundation

at an emergency physician conference to raise awareness of the disorder.

A generation ago the life expectancy for a person with Marfan syndrome

hovered in the 30s. Now, with the advent of medications like beta blockers

to reduce blood pressure and surgery to replace an expanding aortic root

with tougher man-made materials, many Marfan patients can expect to live

into their 70s and beyond.

The key is to monitor the gradual expansion of the aorta, normally about

2.5 centimeters, and to perform surgery just as it approaches the danger

zone, usually about 5 centimeters, although because body size varies

among patients no one number is definitive. Miller and Liang recommend

surgery when the expanding portion of the aorta is double the diameter

of a neighboring normal segment, or sooner if the patient has a family

history of aortic dissection or rupture. The tightrope walk can be tricky.

“You never want to send someone to cardiac surgery who’s feeling

just fine,” says Liang. “But even one minute late is too late.” Survival

during the first 30 days after surgery drops precipitously if a surgeon

must struggle with an acute aortic dissection: from 98.5 percent for

elective surgery to 88.3 percent for emergency surgery.

Physicians at Stanford’s Marfan Center monitor about 120 patients

from all over the country. Many come for yearly checkups, which often

include visits with orthopedic specialists, podiatrists and ophthalmologists

in addition to a cardiac consultation with Liang.

Tick tock

A ballooning aorta is unpredictable and symptomless. It can also be frustrating and scary. Previously stable Marfan patient Linda Lorenz watched her aortic measurements increase rapidly from about 4.9 to 5.5 over the course of a year before her surgery two years ago at age 33.

“There’s nothing that you can do to control it,” she

says, “no medication or diet or exercise. It was just what my body

was doing. I always knew heart surgery was a possibility, but I was always

so stable that I couldn’t really envision going through surgery.

It was a very big shock. It was also hard for my friends to understand

why I had to have heart surgery. They said, ‘But you’re not

sick. Why do you need that?’ ”

Lorenz’s experience showcases the importance of an experienced

support system that addresses the emotional as well as the physical toll

of Marfan syndrome. Before coming to Stanford, Mateyka turned to the

Northern California chapter of the National Marfan Foundation after her

local cardiologist recommended immediate surgery — and then left

town. In addition to family, patients lean on each other and on the physician

and support staff at the center when surgery looms.

“There’s an art to working with patients and finding what

time is right for them,” says Liang. “If an expanding aorta

weighs very heavily on a patient’s mind, I will send them to surgery

earlier.”

In contrast, Mateyka, whose sister had died on the operating table,

was extremely reluctant to consider surgery. “I was very fearful

of it,” she says. But her introduction to Miller, who spoke at a

symposium she attended, calmed her fears. “When he started to speak,

it was very hard for me to listen. But as he went on it became clear

to me that if I ever had to have surgery this would be the man that I

would want to do it. He had ‘the right stuff.’ ”

|

|

Craig Miller, MD |

|

Although the decision to have heart surgery can be wrenching, Marfan

patients who come to Stanford have yet another choice to make: go for

a reliable fix that replaces the entire aortic root with man-made materials

or opt for a relatively new surgery that replaces the aorta while sparing

the patient’s valve. The technically more difficult operation eliminates

the need for a lifelong blood-thinning medication called warfarin to

prevent the formation of deadly blood clots on the mechanical valve.

But the decision is not a no-brainer.

“The gold standard has been to replace both the ascending aorta

and the valve,” says Miller. “But with the valve-sparing operation

the patient doesn’t need warfarin. The trade-off is ‘how long

is this going to last?’ If it only lasts for five years before you

need another operation, then that’s not very good.”

But for Mateyka and Lorenz, the desire to remain off warfarin, which

can bring increased risk of hemorrhage and requires lifelong monthly

blood tests

to keep drug levels optimal, was strong enough to risk the chance of a second

operation somewhere down the line.

“Life with warfarin seemed like a pile of inconveniences and annoyances,” says

Mateyka, who also worried she would be bothered by the audible clicking

of a mechanical valve. “When the possibility of valve sparing came

along, I said ‘yes!’ When Dr. Miller told me that the known

history was about 10 years and that I might need another surgery, I thought ‘Ten

years is great! Who knows what might be discovered in 10 years?’ ”

Although other surgeons also offer valve-sparing surgery, Miller is

one of five surgeons in the world who have performed the operation in

large numbers. Nearly 90 of his patients have opted for the surgery in

the past 10 years, and most show no signs of needing another operation.

During the surgery, Miller removes the expanded portion of the aorta

and the aortic tissue around the valve, leaving it perched above the

heart like an eraser on the end of a pencil. He then slips a section

of woven cloth tubing over the valve, completely encasing it like a fingertip

in a glove. The tube acts as kind of a support hose, stabilizing the

valve while preventing further expansion that could lead to valve failure.

He anchors the valve securely by stitching it to the inside of the tube

graft before reconnecting the coronary arteries that feed the heart muscle

and the loose end of the natural aorta.

“Valve-sparing surgery takes two hours longer than a total replacement,” says

Miller, noting that although many Marfan patients in the country still

have a total replacement, nearly all of his young patients opt for the

valve-sparing operation. “A surgeon has to kind of like it, be committed

to it and have a good sense of 3-D geometry and function. It’s a

very unforgiving operation, and it’s easy to have a disaster.”

|

|

David Liang, MD, PhD |

|

“There are very few places that do valve sparing well,” says

Liang. “It’s technically much more challenging than to just

whack everything off.”

Mateyka and Lorenz are happy with their choices. Miller also performed

a valve-sparing operation in December 2002 on Lorenz’s husband,

Lonn, another Marfan patient. Both Linda and Lonn have numerous relatives

with the Marfan syndrome.

“If any of our family members need surgery, they will come here,” says

Lorenz. “Dr. Miller has an outstanding survival rate. There are

lots of surgeons out there who can just slap in a mechanical valve and

away you go. Dr. Miller had the skills I wanted.”

The availability of valve-sparing surgery also affects the timing of

surgery.

“I have begun to suggest surgery a little earlier than I did before,” says

Liang. “These are young healthy people with good hearts, and this

is a relatively safe operation. If we can leave them with a great result,

and not taking blood thinner, there is less need to delay the operation.”

Sophisticated surgery notwithstanding, Lorenz and Mateyka are grateful

for all the physicians and Stanford staff involved with the Marfan center

and their willingness to help at all costs. Their openness and understanding

may save as many lives as their medical expertise, Mateyka believes.

“Marfan has another unique aspect,” she says, “which is people’s lack of self-esteem due to their physical appearance and their fear of rejection. If they are put off even slightly when they reach out for help, they may never look into that possibility again.” For someone with the Marfan syndrome, that’s likely to be a fatal mistake.

In the genes

Marfan syndrome symptoms are the result of mutations in a single, extremely

large gene called FBN1 that encodes the protein, fibrillin 1. Like magnetized

iron filings, the fibrillin 1 molecules knit themselves together to form

microfibrils — tiny chains that make up connective tissue throughout

the body. Mutations that lead to defects in the amino acids that harness

the fibrillin 1 molecules together, or that generate a shorter-than-normal

protein, throw a wrench in this cooperative model. Different wrenches,

or mutations, cause different symptoms.

“There are well over 100 different mutations in FBN1 that cause

Marfan symptoms,” says Uta Francke, MD, a medical geneticist and

pediatrician at Lucile Packard Children’s Hospital who has collected

tissue samples from the members of about 200 Marfan families over the

past 10 years. “We’re trying to subdivide these mutations into

different populations to correlate the molecular and biochemical aspects

with the severity of clinical symptoms.

“We’ve found that dislocated lenses are more frequently associated

with specific types of mutations, whereas other types of mutations may

cause aneurysms without the skeletal or eye findings,” she adds. “And

there are three families that don’t have heart involvement, just

eye problems.” Francke and other physicians in the Stanford Center

for Marfan Syndrome and Related Connective Tissue Disorders hope one

day to use the information to predict which symptoms individual patients

with known mutations may develop in their lifetimes.

Marfan syndrome has the dubious distinction of requiring only one faulty

copy of FBN1 to generate symptoms. Because all of the fibrillin 1 molecules

work together, even a few defective versions can disrupt the chains.

“In contrast to other diseases, the complete absence of one FBN1

gene doesn’t appear to give problems,” says Francke. “If

it were possible to shut off the mutated FBN1 gene, you would be better

off.”

The huge gene, the large number of mutations and the fact that they

need be present in only one of the two FBN1 genes, make it difficult

to identify Marfan patients simply by analyzing their DNA. Although technological

advances in sequencing are making genetic analysis more common, physicians

like cardiologist David Liang, MD, rely mainly on physical signs for

diagnosis. If a Marfan patient has a well-known Marfan-causing FBN1 mutation,

however, that information can be used to screen other family members

for the disorder.

People with Marfan syndrome who wish to have children face a distressing

dilemma. Because of the domineering nature of the defective FBN1 gene,

they have a 50 percent chance of passing the disorder to their children.

Interestingly, most are not interested in prenatal testing to determine

whether their unborn children are affected, say Francke and Louanne Hudgins,

MD, director of perinatal genetics at Lucile Packard Children’s

Hospital.

“Usually what it comes down to is their social and cultural background,” says

Hudgins. “There are people who say ‘it’s in God’s

hands, we’re going to do it.’ Others say ‘I’m not

going to chance having a child with a problem.’ They can’t

stand the unpredictability.”

Other patients have expressed interest in pre-implantation genetic diagnosis,

in which an embryo created using in vitro fertilization techniques is

tested for a known FBN1 mutation before implantation into the woman’s

uterus.

Big problems for little people: Children with Marfan require expert care

Although many cases of Marfan syndrome escape diagnosis until adulthood, some

are detected much earlier. Gwen Rohrer knew almost immediately that there

was something unique about her newborn son, Dylan.

“Marfan was brought up almost immediately,” she says. “The

doctors were measuring his head, and looking at his fingers.” She

spent 17 months watching and worrying. “I knew that Marfan patients

were tall, so I used to measure him by lining his head up with one of

the bars of the crib and seeing where his feet were,” she says. “It

was kind of unnerving. I knew he was getting long and thin.”

It was an eye examination showing lens dislocation and an echocardiograph

that identified an expanded aortic root that cemented the diagnosis:

Dylan had Marfan syndrome. He had no family history of the disease; the

disorder was caused by a spontaneous mutation in a gene required for

the production of connective tissue.

“They told me he’d be lucky to survive to early adulthood,” Rohrer

says. That was 12 years ago. Fortunately, recent advances in Marfan care,

including prompt and ongoing treatment with beta blockers, have turned

that dire prediction on its head. Doctors now expect Dylan to live a

normal lifespan, thanks to ongoing management that requires the expertise

and coordination of many different disciplines.

Dylan came to Lucile Packard Children’s Hospital in 1991 to consult

with pediatric specialists at the Marfan clinic. Over the years, Packard

physicians worked together to correct Dylan’s scoliosis and sunken

chest, monitor his heart function and repair his failing mitral valve.

“One thing about Marfan syndrome is that everybody is different,” says

Dan Murphy, MD, pediatric cardiologist at Packard Children’s Hospital. “We

want the kids to see the ophthalmologist to get their eyes taken care

of. We may want them to see the orthopedist, because their flat feet

can lead to a lot of foot pain. It’s also very important to teach

the family about the syndrome and the importance of the medication.”

As children with Marfan syndrome grow older, they may rebel against

the disease that prevents them from playing contact sports and leaves

them looking different from their peers. Some might even stop taking

their heart medication in an effort to just be normal.

“In my last 12 years I’ve seen two teenagers who came in with

much larger aortas than the year before,” says Murphy. “In

both cases the kids had stopped taking their medicine.”

Dylan is no stranger to frustration. “He’s mad that he has Marfan syndrome and that he can’t play baseball,” says Rohrer. “Sometimes it becomes overwhelming to him. I tell him ‘If I had known I was going to give birth to you, I would have been an orthopedic surgeon, a cardiologist, a podiatrist, an eye doctor, everything.’ It used to be you just had to wait for the person to die. Nowadays, doctors fix them. They do miracles.”

Marfan care at Stanford

Stanford’s Center for Marfan Syndrome and Related Connective Tissue Disorders

exemplifies the highly regarded, specialized cardiac care offered at Stanford

Hospital & Clinics and Lucile Packard Children’s Hospital. To contact

the center, call (650) 725-8246 or visit the center’s Web site: marfan.stanford.edu.

To learn more about Marfan syndrome or to join the National Marfan Foundation,

visit the foundation’s Web site: www.marfan.org.

Comments? Contact Stanford Medicine at