|

||

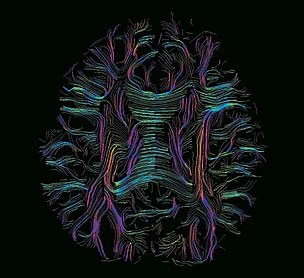

Diffusion-weighted MRI Color-coded white matter fibers reveal the corpus callosum. Appearing as a central band of horizontal blue fibers, the structure connects the brain’s hemispheres. |

||

The brain’s secrets must be handled with care

By Rosanne Spector

Photograph by Roland Bammer

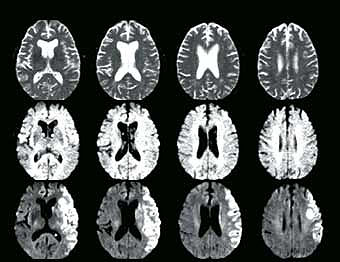

An imaging technique that quickly reveals a brain injury’s size

and location leapt from the lab of radiologist Michael Moseley, PhD,

to hundreds of clinics throughout the world in less than a decade. The

technique, a type of magnetic resonance imaging called diffusion-weighted

MRI, offers improved diagnosis and treatment for stroke.

So what’s next for Moseley and the powerful brain-imaging technique

he developed? Nowadays Moseley, an associate professor in Stanford’s

radiology department, works with colleagues throughout the campus using

the imaging technique to explore human cognition and psychology. He’s

also working with imaging scientists and ethicists to analyze the ethical

issues that arise as a result of neuroimaging findings.

“It won’t be long before neuroimaging will be able to reveal

many of our cognitive strengths and weaknesses,” says Moseley. “This

is exciting for us as researchers. But it makes you stop and think: Will

revealing this information improve someone’s life? Or might it in

some cases change it for the worse?”

As an assistant professor in radiology at the University of California-San

Francisco in 1989, Moseley first used the technique to map the metabolic

changes occurring in very early strokes. He soon realized that the technique,

though not in clinical use at the time, had a huge advantage over standard

clinical imaging tools used on the brain.

“I discovered that I could see strokes only a few hours old,” says

Moseley. He knew that other techniques revealed the damage caused by

strokes many hours or sometimes days after the event, usually too late

to use the information to direct treatment.

Conventional MRI creates images from the variations in materials’ responses

to a strong magnetic field. In medicine, the material usually analyzed

is water, the most abundant element in the body. Instead of simply depicting

water’s concentration in various parts of the brain, Moseley’s

technique went a step further, measuring how fast water diffuses from

place to place.

Stroke patients’ oxygen-starved nerve cells are too impaired to

move water around. As a result, the cells show up clearly using Moseley’s

strategy, though not in regular magnetic resonance images. Moseley first

described this technique’s use in animals in a May 1990 article

in Magnetic

Resonance in Medicine. Since then, the article has been referenced more than

1,500 times by other researchers.

Moseley came to Stanford in 1993 to work with associate professor of

radiology Michael Marks, MD, and neurology professor Greg Albers, MD,

to promote and accelerate the use of diffusion-weighted MRI to treat

stroke.

|

||

Diffusion-weighted MRI Color-coded white matter fibers reveal the corpus callosum. Appearing as a central band of horizontal blue fibers, the structure connects the brain’s hemispheres. |

||

“I’d say we succeeded. MRI manufacturers now offer commercial

diffusion imaging capability,” says Moseley.

There’s no question that imaging specialists are impressed: In

2000 the International Society for Magnetic Resonance in Medicine granted

Moseley its highest honor, the gold medal.

But in the early 1990s the technique’s value was unrecognized.

Stanford and a few other U.S. medical centers began studying the technique’s

usefulness as a marker of stroke during its acute period — the first

few hours after the event, when clinicians believe there is greatest

potential to help patients.

“We began using diffusion-weighted MRI in the clinical setting

in humans and confirmed a number of hypotheses,” says Marks, Stanford

Hospital’s chief of interventional neuroradiology and director of

neuroradiology at the Stanford Stroke Center. “First, we found the

technique is able to detect acute stroke in a matter of minutes after

its onset. Even at less than an hour, diffusion-weighted MRI can indicate

a stroke. At that time, the brain would still appear normal in images

made by other techniques.”

The greater sensitivity of the technique as compared with conventional

MRI reveals a clearer picture of brain damage and illuminates the cause

of the stroke. Knowing the cause — for instance, a clogged vessel

in the brain versus a blockage in an outer vessel — allows neurologists

to plan treatments more effectively.

Albers, who directs the Stanford Stroke Center, Marks and colleagues

continue to fine-tune their use of the technique to help stroke patients. “We

have found that it is a more sensitive way to detect tissue that is injured

or at risk of injury,” Marks says.

Meanwhile, Moseley is working with collaborators to explore other fields,

in particular, cognition and psychology. His latest studies use diffusion

imaging to trace the movement of water through the brain’s white

matter fibers, which he calls the brain’s thoroughfares. “They’re

the neurochemical pathways connecting the gray matter zones,” he

says.

Moseley is collaborating with many Stanford researchers on his new projects.

They’re discovering that characteristics of the fibers — such

as how they are organized and how robust they are — reveal differences

in individuals’ mental workings. Judith Ford, PhD, associate professor

of psychiatry and behavioral sciences, is investigating schizophrenics’ white

matter wiring. Dolf Pfefferbaum, MD, and Edie Sullivan, PhD, are studying

similar patterns in normal and abnormal aging processes. And John Gabrieli,

PhD, associate professor of psychology, is comparing the brains of dyslexics

and regular readers and has already found clear differences.

Gabrieli’s work shows that the white matter at the left temporal-parietal

junction (located above and a little behind the left ear) may be organized

differently in dyslexics. Even among non-dyslexics, better organization

of the temporal-parietal junction appears to be associated with the ability

to read more quickly.

“This is among some of the earliest examples of diffusion imaging being

applied to cognitive performance,” says Moseley. Being able to image cognitive

centers in the brain offers great potential in understanding the human condition.

It may also open up the possibility for testing remediation programs for cognitive

disorders like dyslexia.”

But the technique’s revelations offer reason for pause. Working

with physicist Roland Bammer, PhD, from Stanford’s radiology department

and bioethicist Judy Illes, PhD, at the Stanford Center for Biomedical

Ethics, Moseley has surveyed research on diffusion imaging of cognitive

performance and discussed some ethical issues raised by its use. They

published their report last year in Brain and Cognition.

Among the questions highlighted:

• What constitutes cognitive impairment on the basis of neuroimaging data?

• How should findings of cognitive impairment be conveyed to the patient

and the family?

• What role should neuroimaging have in selecting students or children into

educational or special therapy programs?

• How can researchers share findings without compromising research subjects’ privacy?

The use of diffusion-weighted imaging for diagnosis and treatment of stroke seems straightforward in comparison with its use on this new frontier. It’s reassuring that Stanford researchers are careful pioneers.

Funding sources for this research:

National Institute of Neurologic Diseases and Stroke,

National Center for Research Resources.

Comments? Contact Stanford Medicine at