Can a computer chip fill in for the eye's lost cells?

|

|

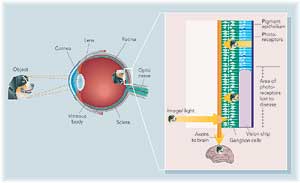

| Fishman and his interdisciplinary team are growing nerve cells on a silicon chip to create an artificial retina. Their goal: connect a camera to the cells, which would send visual information to the brain. The chip would restore vision to people with macular degeneration — which affects one in four Americans over age 65. (larger image available) | |

By Kendall Morgan

Photographs Leslie Williamson

Illustration Ian Worpole

Everyone knows you can’t believe everything you hear. But a growing number of people can’t believe everything they see. Straight lines can turn to squiggles, numbers and letters blink in and out and colors fade to shades of gray. People with the most common cause of blindness — age-related macular degeneration — find that a curtain is gradually drawn across the world.

Luckily, Harvey Fishman, MD, PhD, senior research scientist in ophthalmology, is a visionary. He's a pioneer with his sights set high, and his goal is to rebuild the eye.

Macular degeneration affects one in four Americans over the age of 65, with 130,000 new cases diagnosed each year. As the population ages, the number will continue to rise. As is the case with heart disease, the causes of AMD are likely to be many — the end product of a lifetime of insults to the eye, says Fishman. Today, there are treatments to delay the progression of the disease, but there is no cure.

Fishman, with the help of co-investigator Mark Blumenkranz, MD, professor of ophthalmology, and a diverse team of experts, has set out to attack blindness at its core. The answer, he says, is a silicon vision chip with a command of the language of sight. "This is the wild, wild west of vision research," says Fishman. He and his team will cover a lot of ground before reaching their final destination, but already the future looks brighter.

The early stages of macular degeneration include a wasting away of part of the eye's machinery, a protective cell layer called the pigment epithelium that coats the back of the eye. If clinicians catch the disease early enough, they can restore the lost tissue layer and successfully treat the disease. But without this barrier, cells of the retina — the eye's microprocessor — are gradually lost.

The retina's job is to receive light signals and transmit messages out to ganglion cells and on to the brain. Its role is so sophisticated some consider the retina a miniature brain in itself. In essence, an eye without a retina is like a camera without film, Fishman says. Images can’t be captured.

"The disease knocks out one circuit," Fishman says. "But the rest of the cells are still there, ready to function. We have an opportunity to tap into the eye and replace the lost film."

Fishman isn’t the first to attempt this. The idea dates back to 1956 when a light-sensitive selenium cell placed behind the retina was shown to restore the perception of light in blind patients, however briefly. Since then, groups have sought to access the brain's visual system via a variety of routes: through electrodes ending in the brain or by way of a cuff surrounding the optic nerve — the information superhighway from the eye to the brain.

|

|

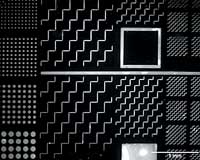

This 1/2-cm-wide chip is stamped with patterns made of growth factors. Its purpose: to test how well the chemicals steer nerve cell growth. The Makings for Eye DramaExperts from Engineering and Medicine Join together against Blindness What do you get when you cross an ophthalmologist with a chemical engineer and an expert in retinal surgery? Real hope for sight restored. When Harvey Fishman, MD, PhD, a senior research scientist in the Department of Ophthalmology, nailed down his plan for a new and improved vision chip, he looked no further than across the street to round up the experts who could make the dream come true. In fact, he got the seed of the idea while eating lunch with Stacey Bent, PhD, an assistant professor of chemical engineering at Stanford and a friend of Fishman's from their days as graduate students. "Harvey has the big picture of what he wants to make happen in the eye, " says Bent." I help figure out how to make it a reality." It's not every day that chemical engineers have the opportunity to oversee surgery and get immediate, firsthand experience with problems in the design of their materials. But it's that kind of interaction that makes this project a winner, Fishman says. Indeed, the research has progressed at an incredibly rapid pace, a synergistic effect of the many great minds behind it. "It's been very stimulating," says retinal surgeon Mark Blumenkranz, MD, professor and chair of ophthalmology. "Everyone is working toward a common goal to restore vision. It couldn't be accomplished by one group alone." Fishman predicts more and more collaboration in the future of scientific research. "We're moving toward great advancements made at the crossroads of diverse disciplines," Fishman says "one chip at a time." Kendall Morgan |

|

A Chip Can Do the Trick

In the early 1990s, researchers began exploring the current method of choice: a prosthetic vision chip implanted into the retina. Vision chip teams are scattered around the world in the United States, Germany and Japan. Still, success has been elusive. Temporary chips have produced the sensation of light in blind patients, but nothing close to useful vision.

Fishman is a relative newcomer to the field of prosthetic retinas and he's full of fresh ideas. His team is working from many different angles to attack problems at every level, from the fabrication of the chip to the practical details of surgery.

The eye responds to light, but also to contrast between light and dark, requiring some cells to be stimulated while others are inhibited. Existing vision chips fall short because they don’t preserve information about contrast, Fishman realized.

"The retina is arranged very precisely," explains Michael Marmor, MD, ophthalmology professor and a project collaborator. "If you just plop a chip down in the middle, you aren’t sending information to the brain in any rational way."

Ultimately, the goal is a chip that would fill in for lost photoreceptors, relaying signals to the brain in a language it can understand. The challenge, then, is to connect single cells in the eye to individual pixels of a digital video camera and to get the chip talking to the eye's intact cells. To accomplish this, the researchers have learned to train nerve cell growth.

First, they make a stamp, "like a child's rubber stamp but in exquisite detail," describes Stacey Bent, PhD, assistant professor of chemical engineering. Rather than stamping in ink, they stamp out a pattern in chemical nerve growth factors. As soon as a growing nerve hits the stamped trail, it sticks to it like glue, growing along in a zigzag or other pattern. It's a trick that makes it possible to grow nerves to the exact locations of pixels on a chip, Bent says.

While other vision chips attempt communication with the healthy cells of the eye via electricity, Fishman hopes to create a chip that can speak the more exact language of chemistry. "Different chemicals tell cells different things," Marmor explains. "If you just shock the retina you can get a sense of light, but with a neurotransmitter you may get a more specific message."

Design and Conquer

The team's research has progressed at an explosive rate. At the May 2002 meeting of the Association for Research in Vision and Ophthalmology, Fishman showed how neurotransmitters and growth factors can stimulate and direct nerve-cell growth on a chip. Now they’ve moved on to questions of chip design and surgery. "If you had told me a year ago that we’d have gotten as far as we have, I would have laughed," Fishman says. Yet plenty of hurdles remain.

"It's promising, but it's a totally open question whether it will work," says David Eagleman, PhD, a neurobiologist at the Salk Institute in La Jolla, Calif. The retinal code hasn’t been completely cracked, so it's unclear whether chips will send the right kind of signal, he says. However, he adds, the brain is amazingly flexible and may be able to adapt to new kinds of visual inputs.

Even if the Stanford chip isn’t the answer to every question in electronic vision, Fishman predicts the technology developed along the way will seep into other important medical arenas from drug delivery to the treatment of spinal-cord injuries. "By combining the best in microtechnology with the best in cell biology," Fishman says, "we will advance on new treatments."

Comments? Contact Stanford Medicine at