|

|

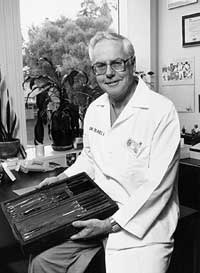

F.W. Blaisdell is a surgeon and Civil War buff. So it's no surprise that the surgical tools his great-grandfather used during the Civil War are among his most treasured possessions. |

|

This year’s Sterling award winner, F. William Blaisdell, MD, talks about trauma’s past, present and future

Robert Tokunaga

A diary stopped a bullet 138 years ago during the Civil War battle at Cold Harbor, Va. If it weren’t for that diary, this year’s J.E. Wallace Sterling Alumni Lifetime Achievement Award wouldn’t be going to F. William Blaisdell, MD, class of 1952.

Blaisdell is a third-generation physician. His father Frank E. Blaisdell Jr., grandfather Frank E. Blaisdell Sr., and maternal-side uncle, Ehler Eiskamp, all graduated from Stanford School of Medicine. William Blaisdell remembers sitting on his grandfather’s lap when he was 5 years old and being told the story of his great-grandfather, Solon G. Blaisdell, who was in the 12th New Hampshire Regiment, which fought at Cold Harbor in the spring of 1864.

“Son, if it weren’t for this diary, you wouldn’t be here,” Blaisdell’s grandfather said, holding up the diary that was in Solon Blaisdell’s coat pocket when he was shot at Cold Harbor. The bullet pierced the diary, and although the force broke some of Solon’s ribs, the bullet did not strike his heart. “If you look in the diary, you can tell the exact day that my great-grandfather was wounded because before that day the writing is missing where the bullet went through the diary,” Blaisdell says. “After that date, my great-grandfather wrote around the bullet hole.”

The Stanford Medical Alumni Association is honoring Blaisdell, known as the father of the modern trauma center, for his work on the frontlines of medicine. The award recognizes the 74-year-old UC-Davis Medical Center professor and emeritus

chairman of surgery for his dedication to teaching and tenacity in trauma research. Blaisdell is currently chief of surgery for the VA Northern California Health Care System, based in Sacramento. He is board-certified in general surgery, thoracic surgery, vascular surgery and in surgical critical care.

Stanford MD recently sat down with Blaisdell in his office at UCDMC in Sacramento.

Stanford MD: Earlier this year you gave a lecture on medical and surgical advances during the Civil War. Did your interest in this subject come from your great-grandfather’s experience?

F.W. Blaisdell: Yes. At the start of the war in 1861, there was no organized casualty care. Patients just lay on the battlefield and what ambulances there were fled with the Union troops. By 1864 there was a system of organized care on the battlefield. At Cold Harbor, 7,000 were wounded in the first 30 minutes. How did the medical officers handle that? I became interested in how the organization of injury care progressed during the war.

SMD: How did you go from cardiovascular surgery to trauma care?

FWB: Cardiovascular training is very good background for trauma care. The biggest problem in emergency surgery is control of bleeding.

SMD: You were the original architect for establishing the trauma center at San Francisco General Hospital. How did that come about?

FWB: The city of San Francisco up until 1966 was a benign place. You could walk through most of the streets at night without fear. But in 1966, which was the year I went to San Francisco General, things were changing, with the hippies and the drug culture. Our data at San Francisco General showed that between 1966 and ’67, crimes of violence had doubled. The following year they doubled again. The following year they nearly doubled for a third time. All of a sudden the city became a violent place. Thanks to the citywide ambulance system, which brought all emergencies exclusively to San Francisco General, our emergency room was overwhelmed. In order to take care of the epidemic of emergencies, we formalized our trauma care and assigned one group of residents to the emergency room to deal with all of the emergencies that presented. The remaining group of residents took care of the elective problems. What gave our program national notoriety was that we had the first complete program to encompass an entire city.

SMD: What made you decide to come to the UC-Davis Medical Center in 1978?

FWB: After 12 years at San Francisco General, I needed a new challenge. UC-Davis Medical Center was still in its infancy. In 1978 it was still a county hospital trying to become a university hospital. I found it very satisfying developing the surgical program. At present we’re the most solvent medical center of all of the academic medical centers in California. I say with some pride that a lot of that came about because of trauma and related surgical programs.

SMD: What changes do you expect in trauma surgery in the next 10 years?

FWB: We’ll continue to see fewer open operations in trauma care and the use of CT and MRI to enhance our diagnostic abilities.

SMD: Like UC-Davis, Stanford is also a trauma center [a hospital specially equipped to treat serious injuries — Ed.]. What are the benefits to the medical center?

FWB: It’s excellent training for residents and provides a great experience in critical care. It puts them in a situation of being able to handle almost anything. Trauma prepares them to deal with any part of the body. It’s a chance to use all of their medical training.

SMD: What are the greatest challenges facing surgical training?

FWB: The number of applicants for general surgery is way down. Why? Because of the perceived lifestyle. The general surgeon works hard, hours are long and the stress can be great.

SMD: What do you say to convince someone that surgery and trauma care are rewarding specialties?

FWB: I present a case for them. The important thing, I believe, is to enjoy your work. If you don’t enjoy your work, there are going to be problems at home and work. I heard a dermatologist recently complaining that so many of the people who are opting for dermatology are just opting for the lifestyle. Mostly 9-to-5 and no emergencies. But they really don’t enjoy it.

SMD: Do you enjoy the action that comes with trauma care?

FWB: Yes. I also enjoy the black box of not knowing what you’re going to encounter.

Comments? Contact Stanford Medicine at