|

|

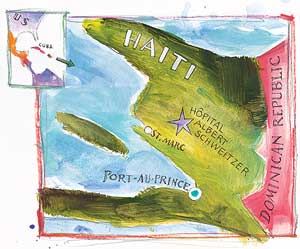

Life in Haiti is rich in lessons for surgical trainees

"From this high, it doesn't look like a hellhole"

chief

of Stanford's general surgery division, in January 2002, as he looked

out the window of an American Airlines Boeing 737 descending past 8,000-foot

peaks toward the clear, blue Caribbean and the single runway at Port-au-Prince

airport.

By Mike Goodkind

Illustrations by Stan Fellows

Inside the wood-paneled library of the 190-bed Hôpital Albert Schweitzer in rural Haiti, the drumbeats from a neighboring settlement's voodoo ceremony the night before are only a memory and the smells from visitors' cooking fires are blocked by the closed door.

Diagnostic radiologist Phil Karsell, MD, on a one-month sabbatical from the Mayo Clinic in Minnesota, takes questions about the hospital's patients from a group of about 30 Haitian, U.S. and European physicians, nurses, administrators and guests, one of whom is Stanford surgical resident Marion Henry, MD.

"In a perfect world, we would ... " is Karsell's frequent preface to advice that the group knows most definitely does not apply here in Deschapelles. Yet the group is hungry to learn just what might apply to their patients in the 48-year-old hospital, 90 miles from the capital of Port-au-Prince.

Yes, says Karsell, the puzzling dark spot on the chest X-ray might be cancer or, in this milieu, might just as likely be tuberculosis. "In the best of all worlds," Karsell suggests, a CT scan or a subspecialist consultation might be useful — but in Haiti it makes more sense to begin treatment for TB.

While the discussion about resource constraints and efficient treatment would be familiar territory for a physician at Stanford, what comes next is peculiarly Third World. Chief operating officer Jackie Gautier, MD, a Haitian who formerly served as the hospital's pediatric chief, announces that the hospital's supply of post-anesthesia pain medications is used up with little likelihood it will be replenished in the next month or two.

"Why can't you hand-carry some in on the next plane?" one physician asks. Gautier smiles thinly. Paperwork, not logistics, is involved, Gautier says diplomatically. Later, other physicians explain that while the hospital is entitled to import its supplies and medications duty free, the bankrupt Haitian government or an official might be waiting for an unofficial payment. In any case, the medication isn't coming.

"Well, this means we will have to stop surgeries. We cannot perform surgery without post-anesthesia pain medications," says Andreas Allemann, MD, a Swiss surgeon on a three-year tour at the hospital. Kevin O'Connor, MD, a visiting Mayo internist training for a second career as a psychiatrist, suggests that fentanyl, which the hospital has on hand for OR use, also works as a post-surgical painkiller. "We do that all the time in the States. You just have to reduce the dosage," O'Connor notes. The conference breaks with an interim solution.

|

|

A gift of a hospital for HaitiHaiti, the poorest nation in the Western hemisphere, is nearly devoid of public health care and in fact has virtually no infrastructure of any kind. For example, Port-au-Prince has no public garbage pickup, and trash cans are few. As a result, refuse piles up in the streets. For many rural Haitians, Hôpital Albert Schweitzer offers the only possibility for health care after the bókó, or voodoo priest, fails to arouse the appropriate healing spirits. • In 2000, the hospital admitted 13,000 patients and cared for 163,000 outpatients at the Deschapelles facility and at seven outpatient dispensaries in the region of some 258,000 persons that the Haitian government has mandated as the hospital's service area. • The private hospital's presence in this desperately poor country is the legacy of one of the world's richest families. William Larimer "Larry" Mellon, the son of the Pittsburgh Mellon steel family, and his wife Gwen founded the hospital in 1954. The couple was inspired by African missionary Albert Schweitzer's philosophy, "reverence for life," a slogan emblazoned over the hospital's entrance. • Coincidentally, Stanford has old ties to the hospital. During a sabbatical year, Loren "Yank" Chandler, MD, Stanford medical school dean from 1933 to 1953, was Hôpital Albert Schweitzer's first chief of surgery. He and his wife Alva arrived before the hospital opened in 1954 and helped uncrate supplies while working to set up a program, according to Gwen Mellon's biography. • Since Larry Mellon's death in 1989, the hospital has relied increasingly on donations and outside funding, including a current $2.5-million, five-year grant for women's health from the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation of Seattle. • Readers interested in learning more about the hospital can visit www.hashaiti.org or contact the Grant Foundation in Sarasota, Fla., (941) 752-1525 |

|

|

Lessons Learned in a Far-From-Perfect World

From Ralph Greco's perspective, the unrelenting demand on the hospital's staff to cope with the unexpected — such as a sudden shortage of medications easily obtainable in the United States — offers invaluable lessons to surgical trainees on rotation at the Haitian hospital.

For 27 years, Greco has made working visits to the hospital, first as a Yale surgical resident, later as chief of surgery at Robert Wood Johnson University Hospital, and since summer 2000 as Stanford's Johnson & Johnson professor of surgery. Now Greco hopes to develop a surgical rotation for Stanford trainees that will include Hôpital Albert Schweitzer as an option.

The contrast of desperate need and limited resources found in Haiti offers the department's residents an extraordinary educational opportunity, Greco says.

Haiti's health needs are overwhelming, notes Hôpital Albert Schweitzer's CEO, Henry Perry III, MD. For example, the country's infant mortality in 2000 was 86 per 1,000 live births, twice as high as in Honduras and more than 10 times higher than in the United States, Perry says.

Furthermore, the unstable politics and lack of infrastructure in Haiti provide a unique environment for learning to cope calmly with extreme adversity, says Greco.

"Papa Doc [François Duvalier, dictator from 1957-71] left a legacy not just of terror but of terror arbitrarily applied. The population lived in fear not only because they could be brutalized at any moment but also because they couldn't predict who would be struck or when. This created a sense of helplessness and a feeling that any attempts to secure order in life — except through magic or religion — were hopeless. This lack of order is very, very uncomfortable for scientists to deal with, but by starting to understand this phenomenon our trainees will leave here stronger," explains Greco.

"Our trainees and attendings who come here learn not only to think out of the box — they learn how to understand their ‘out-of-the-box' feelings and trust their judgment," Greco adds. "New experiences, even if never replicated ‘in a perfect world,' teach doctors how to deal with the unexpected — and the unexpected they will surely experience in their careers."

And because Haiti's problems have been festering for centuries and lend themselves to no easy solutions, working at the hospital provides a lesson in humility for trainees, who leave behind their cell phones and dreams of success for a few weeks, says Greco.

Greco and Perry cite many benefits to trainees. "You're forced to rely on and develop your clinical skills — and the confidence that comes from being able to do so," Greco says.

Lessons learned in Haiti very likely will pay off back at home in the United States, says CEO Perry. The global increase in population mobility makes familiarity with Third World ills more relevant than ever for "First World" physicians. Common diseases trainees confront at the hospital, such as tuberculosis and malaria, are diseases U.S. doctors are forced to confront more frequently in their practices as more visitors and immigrants from Third World countries become patients at U.S. health facilities, says Perry.

Put simply, "It's important for physicians to have some notion of what the world is like," he says.

Honing diagnostic skills is one advantage. But there are many others, Greco says. For example, trainees must learn to approach diagnosis and treatment in a manner in keeping with their Haitian setting.

"Around here, you can't ask, ‘What does the CT scan say?' ‘What does the consultant think?'" notes Greco.

And beyond that, trainees learn that even if a CT scan were available, it may be irrelevant. A case in point: When a member of the hospital's staff sent a possible brain tumor patient to Port-au-Prince for a CT scan, surgeon Allemann became upset — because even if the test had uncovered a brain tumor, the hospital had no neurosurgeon to operate. "What good would a CT scan do?" asks Allemann.

|

|

Learning out of schoolFirst-year general surgery resident Marion Henry has long sought adventures outside the classroom. An intercollegiate ice hockey player at Princeton, Marion Henry taught literacy in New York for two years before entering medical school at Stanford. Once enrolled here she spent time teaching rural health workers in New Guinea, assisting the staff at Haiti's Hôpital Albert Schweitzer and working and learning in a rural health clinic in Peru. Henry says this about the health-care learning experience in Third World settings: "It teaches you to rely on what you see, hear and feel, and not on what some lab value or machine tells you. You learn to be more attentive to physical history and exams and to then use that to build a picture. Training at Stanford is clinic-centered by design. But when you go to a place such as Haiti, there is more exposure to the social context. The experience teaches you to be a better clinician wherever you are." |

|

One Trainee's Perspective

Marion Henry is one of four Stanford trainees who joined Greco in April 2000 on his first trip as a Stanford surgeon. She was back in Haiti with Greco on his January 2002 trip.

In Haiti, trainees learn to deal with basics. When Henry arrived as a visitor in January, she brought a large bag of surgical gloves. "The hospital has sterile gloves for the OR, but gloves in the wards are washed and reused. The staff can always use these," she says.

Part of the appeal of the Haiti experience, says Henry, is the collegial atmosphere. "In this environment, it is a little more comfortable to share an idea with the team. There's less of a hierarchy. New ideas are more readily shared here than at a hospital in the States."

And simply sitting in on the morning conferences is an education in how medical professionals under unspeakable conditions can pool their resources for the good of their patients.

Henry believes the hospital is making a difference and is glad to be part of it. "Last year I participated in three bowel obstruction surgeries in two weeks. If there hadn't been a hospital here, those patients would have surely died. The vehicle-accident patients we saw in traction this morning would most assuredly spend the rest of their lives as quadriplegics without the services of this hospital."

Building the Stanford Connection

In the coming months, Greco hopes to get the go-ahead from the medical team at Hôpital Albert Schweitzer and from Stanford administrators to establish an ongoing training program for Stanford surgical residents. His goal is to establish an elective rotation that would send four to six residents a year to train for a month in Haiti. Ideally, residents would start within the year.

Undeniably, Greco has a powerful motivation to get a Stanford program up and running: his desire to return to Haiti again and again to teach and care for patients.

"When I first went to Haiti, I was grateful to learn that even under extraordinarily difficult conditions, I could somehow find a way to help patients," says Greco.

"I now have the additional privilege of watching trainees smile as they make the same discovery. It's almost counterintuitive, but a harsh, often tragic, environment has the power to affirm our sense of worth. I come back to remind myself of these simple truths and to pass the message on to others."

Comments? Contact Stanford Medicine at