|

|

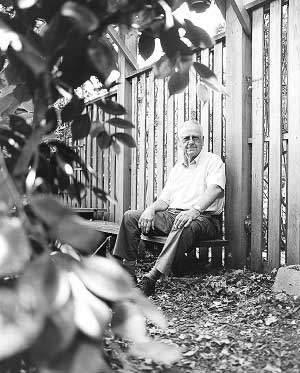

William P. Creger, MD, recalls Stanford medical school in the '40s and '50s. |

|

Medical School Recollection

An alumnus sees new challenges for medical education

By Joyce Thomas

Photograph: Leslie Williamson

Was it a special place or were we special people at a special time?" muses William P. Creger, MD, class of 1947, as he recalls his medical school days in San Francisco. "We were young, it was 1945 and we were winning the war and living in a fascinating city."

More than 50 years later, Creger, now a Stanford emeritus professor of medicine (hematology), recalls some non-medical details that made lasting impressions.

"I remember our student body had center, first-balcony boxes for the entire season of the symphony at $56 a seat. Several of us," he says, "would grandly arrive at the valet parking area of the Opera House in a huge 1926 Packard."

For the bookish, there was Evans' bookstore on California Street near Polk. Evans and his soldier brother had bought up fine books very cheaply from the war-torn countries of Europe. "I still have a large volume of engravings by William Hogarth [18th-century English painter and engraver] with $12.50 penciled on the flyleaf," says Creger.

"Of course, like all young people, we were constantly hungry," he remarks. "Some of us favored Joe's at Fillmore and Chestnut streets, where a steak sandwich on sourdough with green peppers was 75 cents. I think minestrone was included but not wine. Or an adequate, if colorless, meal could be had for just 40 cents at the hospital diet kitchen."

Adjacent to the "new" hospital was a fine tennis court, later sacrificed to parking cars. Creger says, "I was bitter about this alteration because tennis was the one sport in which I could show off a bit."

But what was the school in San Francisco like? It was small and rather provincial, says Creger. Most students were from the West. Curricula were classical. Clinical training was good but limited by a confining old hospital and a trip across town to the city hospital. Research was modest, in quantity at least.

All these recollections are real enough, he says, but comprised as they are of equal parts of coming of age in a wonderful city and stimulating learning in a wonderful field, it's hard to weigh them separately.

One facet of the medical school in the early '50s deserves special credit: its honest self-appraisal that it needed a renaissance of site, curriculum and faculty. The school needed to join the breadth and depth of the parent university and contribute more to the medical research effort of the nation, states Creger.

This was accomplished "brilliantly," he says. "By 1959 we had opened a new shop on the Stanford campus. The new basic science faculty was superb and there was an infusion of medical students from across the country, in response to the new science and the new flexible curriculum."

But Stanford and other medical schools cannot rest on their laurels, cautions Creger, especially given the difficulty in matching income and costs and the confusion over health-policy issues that medical schools now face. So "I propose and advise that the country's medical school deans take a new step: Construct their view of medical education and practice for the 21st century, enlist the help of the country's journalists and give the Congress no peace.

"Success of these efforts would, indeed, be something to reminisce about in 50 years or so," says Creger.

Comments? Contact Stanford Medicine at