Opening up

The evolving world of surgery

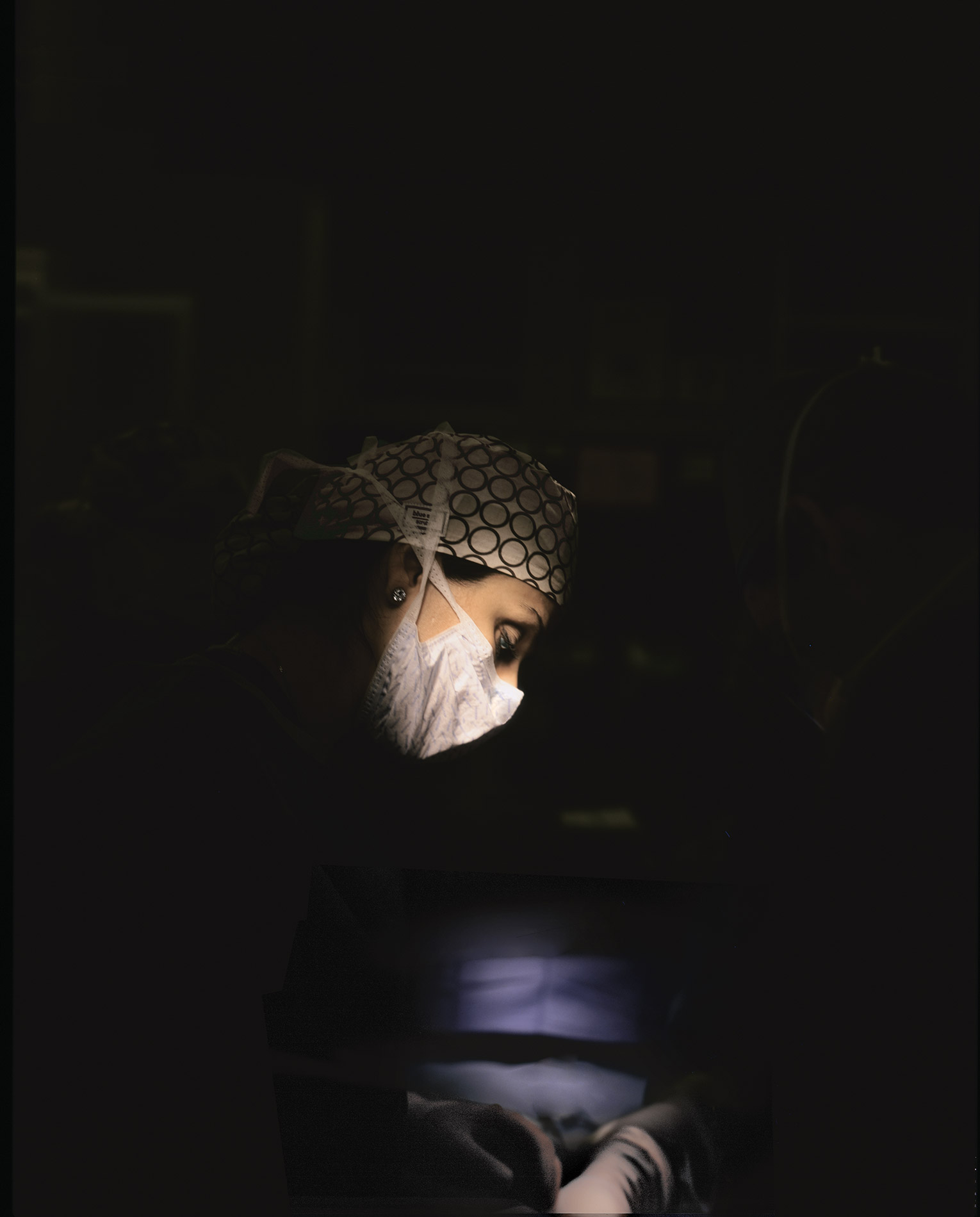

Sepideh Gholami stood at the surgeon’s elbow, using a metal prong to expose the dark, tennis ball of a tumor in the young patient’s colon. It was her third year at Stanford medical school, and she’d been a reluctant student of surgery, as the operating room seemed like an alien, foreboding place.

Extras

But in her first week at Kaiser Permanente Santa Clara Medical Center, she was taken in by the artistry of the process – the ritual passing of the instruments and the deft movements of the surgeon’s hands as he carefully cut out the cancer. There was a rhythm to it. It felt like dancing, one of her passions.

The surgeon moved quickly, and in short order life would change for the patient. Gholami felt a connection with him, a Mexican man in his 30s who had come to the hospital surrounded by a very large family.

“I remember going to the family afterward, saying that we were able to get it all out and seeing the glow in their faces,” she recalls. “That feeling stuck with me.”

It rekindled a childhood memory: the glow on her own mother’s face when she learned the cancer had been extracted from her breast.

“I thought, ‘This is what happened to my mom,’ who is now disease-free. This is how she must have felt.”

And so Gholami, 32, became seduced by the practice of surgery, ultimately setting her sights on a career as a surgical oncologist.

Now finishing her sixth year as a surgical resident at Stanford Hospital, Gholami, MD, is being raised in an era of burgeoning surgical technologies, changing training practices and a more collaborative culture that is opening its gates to women. She must master a breathtaking array of new surgical tools, all designed to minimize the impact of the surgeon’s knife. With these tools, procedures that once produced a foot-long scar on a patient’s abdomen have been reduced to operations that leave a few pencil-thin marks. And surgeons are pushing the boundaries with operations that need no incision at all, such as tumor removal through the nose, the ear or the mouth.

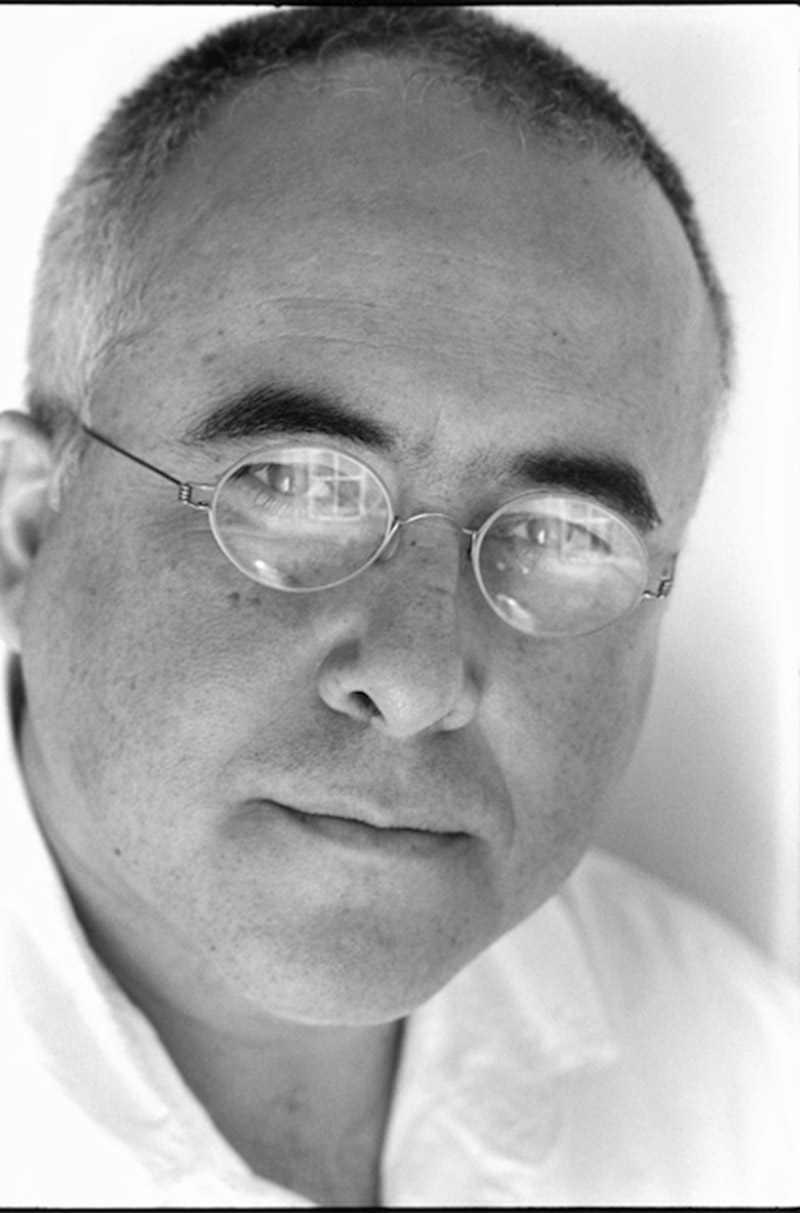

“When I was a medical student, I remember a senior surgeon saying, ‘Big hole, big surgeon,’” recalls Tom Krummel, MD, the Emile Holman Professor and chair of the Department of Surgery. “That, of course, has changed. We do the same big operation. We just don’t make a big hole.”

Now surgeons commonly carry out big procedures through small incisions. They slide in a tiny video camera, called an endoscope, which transmits the view of the surgical site to a monitor in the operating room. Through additional small incisions or through the tube-shaped endoscope itself they slide in other surgical tools – maneuvering them with handles that extend outside the body. “The collateral damage of an incision is no longer the badge of what I can do,” says Krummel. “It’s harder to work with chopsticks, which is essentially what we’re doing.”

The benefits of surgery’s advances have been enormous for patients, who now undergo some 50 million surgical procedures a year in the United States alone.

The profession Gholami is entering today is a far cry from the surgery of the early 1800s, when modern practices had their beginnings, notes surgeon Atul Gawande, MD, in a 2012 New England Journal of Medicine article. Back then, a Boston surgeon performed the first reported cataract removal using a cornea knife to successfully excise the thickened capsule from the eye of an unanesthetized patient, who regained his sight. Other surgical techniques soon followed, including extraction of kidney stones and treatment of arterial aneurysms and gunshot wounds. But these procedures could be brutally painful and were limited in part by the threat of infection and the lack of anesthesia, whose introduction in the mid-1800s revolutionized the field, says Gawande.

More than 125 years later, the second revolution in surgery came with the advent of endoscopy and other techniques to minimize the intrusion of the surgeon’s knife. Less-invasive surgeries cause less pain and blood loss, reduce the risk of infection and lead to quicker recoveries, as many procedures that once required long hospitalizations can be done without an overnight stay.

A striking example is surgery for patients with an aortic aneurysm, a bubble in the aorta that can rupture and cause death. Patients used to undergo a massive, risky procedure in which surgeons made a foot-long opening in the abdomen to remove the damaged part of the artery and then sewed a Dacron tube in its place. Now it’s done with two small holes in the groin, as surgeons snake a catheter up into the aorta and repair the aneurysm with a stent graft – a procedure pioneered at Stanford. Most patients now go home the next day, whereas in the past they would typically spend seven days in the hospital, including two in the intensive care unit.

“The transition to less-invasive, image-guided therapy has revolutionized vascular surgery and requires us all to continue to learn new skills and innovate, all for improved patient care,” says Jason Lee, MD, director of endovascular surgery at Stanford and a principal investigator on several trials of devices to make it easier for patients to recover from surgery.

With the shift to minimalist procedures, “Surgeons have had to change mentality,” says David Spain, MD, chief of trauma and critical care surgery. “If you’re doing a procedure with small incisions, are you less of a surgeon? It’s kind of an identity crisis for surgeons,” he says, especially for those like him who trained in the 1970s and 1980s, when big, open surgeries were the bread and butter of the practice.

On the other hand, there is the satisfaction of fixing a patient’s life-threatening problem with a few tiny cuts and a quick hospital stay. “You’re doing the same big surgery on the inside,” says colorectal surgeon Natalie Kirilcuk, MD, one of a younger generation of surgeons. “I feel a sense of accomplishment when I do it with as little external impact as possible. You can take out an entire colon with a few poke holes and a small incision.”

New imaging and navigation tools also play a key role in modern surgery, exposing previously hidden structures in the body to help guide surgeons to minute targets without harming critical structures.

For instance, with advanced brain imaging, neurosurgeons can visualize structures deep within the skull in three dimensions, enabling them to extract malformed vessels through a 5-millimeter (a fifth of an inch) opening or to successfully remove a tumor near the brain stem, a previously impossible feat, says Gary Steinberg, MD, PhD, the Bernard and Ronni Lacroute-William Randolph Hearst Professor in neurosurgery.

“We couldn’t get there without devastating the patient,” says Steinberg, chair of the Department of Neurosurgery. “With current imaging, we can view the brain with a precision of 1 to 2 millimeters,” or less than a tenth of an inch.

The development of surgical robots, a form of computer-assisted surgery, has added another dimension to the field. With robots, a surgeon sitting at a console in the operating room can manipulate robotic tools inside the body through a single incision.

Surgeons love working with their hands, and surgical robots are helping bring back the “feel” of traditional surgery as the surgeon uses dexterous hand and wrist movements to guide the robotic arms, which serve as a natural extension of the human hand. “It restores the attributes of open surgery without making a big hole,” says Krummel, a robotics expert who came to Stanford in 1998 in part to expand the university’s robotics program by bringing together surgery and engineering. Robots have been used in more than 1.5 million procedures nationwide and are now the tool of choice in prostate surgery, gynecologic surgery and some other procedures.

With the exponential growth in new tools, even highly experienced hands like those of Jeffrey Norton, MD, the Robert L. and Mary Ellenburg Professor in Surgery and chief of general surgery, have had to relearn some aspects of the trade. “You have to learn to do new things. It’s like starting over,” says Norton, who is widely recognized for his skills as a surgical oncologist.

At times, Gholami says she has found herself in the operating room with mentors who themselves are acclimating to some new piece of technology. “They are still in their own learning curve,” she says. “So when you are scrubbing, it may be with an attending who hasn’t done it many times. So he or she may be more cautious.”

As surgical technology has soared, so has patient demand, along with the number of skilled practitioners. By 2008, nearly one in every five active physicians in the United States was a surgeon, according to the American College of Surgeons. These master technicians now have some 2,500 procedures at their disposal, Gawande notes in his article.

And because of greater ease and safety, these procedures are performed far more often. At the current rate, projects Gawande, the average person in the United States will have seven surgical procedures in his or her lifetime.

“The technological refinement of our abilities to manipulate the human body has been nothing short of miraculous,” Gawande writes.

For Gholami, it was a long, hard road into the operating room, which was far from her consciousness as a youngster in her native Iran. At the age of 5, she fled the Iranian revolution with her family in the early 1980s and grew up in a hostel for asylum seekers in Germany. Her father, an auto mechanic, inspired her to use her hands to fix things. As a child, she remembers repeatedly taking apart the videocassette recorder to clean and put back together, all out of sheer delight over the workings of the device. She envisioned herself as a mechanic one day, though it was hardly a vision of herself as a skilled mechanic of the human torso.

Her life as an immigrant in Germany was hard, so she jumped at the chance to visit an uncle in Northern California whom she barely knew. There happened to be some fine universities nearby, and she was fortunate to attend the University of California-Davis and, later, Stanford medical school, from which she graduated in 2008.

Even in medical school, surgery was far from her mind. She chose it as her first rotation “just to get it out of the way,” she says.’

But she quickly became seduced by the exhilarating tempo in the OR and the gratification that comes from immediately fixing a problem and restoring someone to life.

“Surgery is very fast–paced. It is so fast-paced that a lot of people get lost and think it’s too much for them – you have to keep 500 things in your head,” she says.

There is a very quick turnaround: “You round on your patients in the morning, then do the operations and in between cases or after see patients again. It’s not like other fields of medicine – it’s a very different type of lifestyle. … I don’t think it’s for everyone, but if you do love it, as I do, you will feed off it. There may be days when I go without sleep and am still going. But when I get out of the OR, it doesn’t matter if I slept last night or not – it is so gratifying. There is nothing else I could envision myself doing.”

The demands are evident on a recent morning, as Gholami works alongside Spain to repair a hernia – a weakness in the abdominal wall that showed up as a large lump on the patient’s midsection. They take turns controlling a slim, tubular endoscope, known as a laparoscope, and other tools, periodically alternating places at the operating table in a quick do-si-do. “See, surgery is like a dance,” says Gholami, her dark oval eyes framed by her surgical mask and cap. “Sometimes you have a good partner,” responds Spain. “Other times you have to lead them around.”

After estimating the size of the surgical site, Spain cuts out a circular mesh shield – “arts and crafts,” he calls it – to restrain the gaping hernia. Gholami folds the mesh, inserts it through the laparoscopic tube and positions it inside the body. She and Spain then work in tandem over the patient’s midsection, which glows in the laparoscopic light, their hands weaving in and out as they stitch down the mesh and staple it in place. “So pretty,” Gholami says of their handiwork. “Yes, pretty,” says Spain. “I hope it works.”

Gholami is then off at a run to the emergency room to examine a young car accident victim, to review scans and order surgery for a man with a perforated bowel, and check lab results for a gallbladder patient.

“This is the challenge, you see. Everything happens so fast,” she says as she jogs back to the OR for another hernia fix.

Surgeons are, by nature, nimble practitioners, quick to move and act. They have to be, for while a patient’s internal organs are exposed, open to possible infection, there’s no time for long debates about what to do next.

They also feel a special connection to their patients, who put their full faith in the clinician while anesthetized on the operating table, often in an undignified pose. “The patients are completely incapacitated, so when you are in the OR, you have to do the right thing – make the right decision,” says Kirilcuk, a clinical instructor of surgery. “I think surgeons have a lot of passion for their patients because of the trust that patients put in us.”

Gholami began her training at a time when the teaching of surgery was at a crossroads. In 2003, the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education, the national accrediting group for medical and surgical training programs, imposed the first of a new set of work rules that included a strict, 80-hour work week limit for residents. These regulations have caused much consternation among medical educators, particularly in the surgical community. Surgeons in their 50s, like Spain, remember their training days when they virtually lived in the hospital, spending 100 hours a week or more there, on call every other night and consoling patients at the bedside for long stretches of time.

It was dog-eat-dog in the surgical world those days, with interns angling to seize every opportunity to be in the operating room so they could beat the competition and survive the program, he says. With trainees today limited to working 80 hours, “they have 20 percent fewer opportunities to see stuff,” says Spain, who is the Ned and Carol Spieker Endowed Professor of Surgery. “A lot of people from my generation, who grew up in the competitive era, think those rules are killing surgery. Though I don’t agree.”

Many argue that surgical trainees back then were so tired that they were prone to mistakes and weren’t really able to soak up what they were learning – the rationale behind the work limits, which were strengthened in 2011. Krummel, the department chair, remembers falling asleep at the wheel after being on call for 36 hours as a resident in Richmond, Va., in 1982. “I could have killed someone,” he says. “I woke up real fast when I hit the guardrail.” Luckily, no one was injured.

He also questions whether patients benefited from having tired trainees leaning over the operating table. “We all know patients for whom we didn’t exactly deliver what was needed,” he says. “We blundered along. It was learning on the job. We might have been having trouble getting the appendix out. We could have used some gray hair in the operating room, but it was a sign of weakness to call for help. Our trainees today are much better – they don’t worry about calling for help.”

James Chang, MD, professor and chief of plastic and reconstructive surgery, says when he was a medical student at Yale in the 1990s, surgery residents routinely slept through lectures. He saw them as tired, hungry and unhappy. “They couldn’t see the end of the tunnel in their education.” Today, he says, “As a result of getting good sleep and having an outside life, residents are happier people. They’re awake and engaged.”

Stanford has adapted to the new work rules by developing a more structured curriculum, including time in simulation, to help residents master the vast body of knowledge and the bewildering array of technologies and procedures they are likely to encounter in their practices.

Medical simulation, says Krummel, is crucial. “Simulation allows you to develop a curriculum in a more thoughtful, organized way,” rather than have residents scrub in for whatever patient happens to come in that day.

He founded the Goodman Simulation Center at Stanford Hospital & Clinics in 2007 and helped develop the Roy B. Cohn Bioskills Laboratories, a rare type of facility where surgical trainees use cadavers to hone their skills. Simulation allows trainees to practice procedures over and over before they even see a patient, says Lee, an associate professor of surgery. With simulation, a trainee can face a console resembling a video game and manipulate wires and catheters inside a box, rehearsing what it’s like to do an angiogram, say, or install a stent.

“We entrust our lives to pilots and they train by working on simulators,” Lee says. “We entrust our lives to surgeons and yet we have no metric to measure performance other than they have practiced alongside someone for five years. What if pilots didn’t practice until they did the real thing?

“It makes education more efficient, and efficiency breeds many advantages,” he adds. “They can be here in the hospital less and incorporate material for a better work-life balance.”

Lee is among those in the surgical community who believe residents graduate with too little experience to enter independent practice – a subject of much contention. In addition to today’s limits on training hours, surgery residents no longer spend time in the operating room on their own. Changing government reimbursement practices, which require an attending physician to be present, as well as more scrutiny of medical procedures by government and regulatory groups, have limited the autonomy of surgeons-in-training.

As a result, nearly 40 percent of surgery residents said in a recent survey that they lacked confidence in their skills after five years of training, according to a study published in September 2013 in the Annals of Surgery. Moreover, 43 percent of fellowship directors interviewed said incoming residents couldn’t do 30 minutes of a procedure on their own, though most said the residents were up to speed by the time they finished the fellowship program.

Gholami bristles at the idea that today’s surgery residents aren’t as well-trained because they don’t have enough exposure to different experiences and procedures. “I think that’s inaccurate,” she says. “Overall you can’t say we’re less trained. Training today is just different than it was in the past.”

Moreover, she says residents now routinely hone their skills and gain added expertise in specialty areas by pursuing one- or two-year fellowships after their four to seven years of residency, depending on the specialty, and their four years in medical school. Indeed, more than 80 percent today choose to go on to fellowship programs after residency, according to the Annals study.

To help smooth the transition from residency to general surgery practice, the American College of Surgeons has developed a fellowship. The program supplements the residency curriculum so trainees have the confidence and mastery to lead independent practices.

Not only have surgical practices and training changed, so have the faces of surgeons – literally. Where women were once personae non gratae in the operating room, they are now entering it in record numbers, accounting for 21.3 percent of the nation’s nearly 136,000 practicing surgeons in 2009. Though women comprise a smaller portion of the surgical workforce than of the medical profession as a whole – where they account for 30.5 percent – a growing number of female trainees are entering the pipeline, according to the American College of Surgeons. Women accounted for 37.5 percent of surgical residents and fellows in accredited programs in 2008.

Surgery traditionally was considered a demanding job, designed for tough guys, so that even getting married was given a second thought. Krummel remembers one of his mentors at Johns Hopkins University having to seek permission from his supervisors to marry. And Spain says in his day, for a surgeon to have a wife who was pregnant was considered “marginally acceptable,” as children could prove to be a distraction from work.

As department chair, Krummel has made recruiting women to the department a priority. When he arrived at Stanford in 1998, women accounted for only 9 percent of surgery’s full-time faculty, including those in emergency medicine. Now, 35 percent of the faculty and 45 percent of trainees are female, he says.

“We’ve been lucky here at Stanford to have female mentors who are great role models,” Gholami says. “So the issue of women in surgery is not a problem here, though I’ve heard stories of difficulties elsewhere – that there is a gender imbalance.”

“I think if you don’t have a role model, it’s hard for women to imagine how they could be surgeons,” Krummel says.

Sherry Wren, MD, a professor of surgery, says she had to almost fight her way into the field more than 25 years ago. “People actively tried to discourage me from going into surgery,” she says. “It was the boys’ sport.” But she loved the profession’s artistry and the process of puzzling through patient problems and making decisions. Her role model was a feisty male surgeon in medical school who urged her to get surgical training.

When she arrived at Yale as a resident in 1986, she was one woman among 17 men and had to endure lectures about the style of her curly red hair – which drew more attention than her performance – and the need to wear pearls in the operating room, she says. “It was a really different world then,” says Wren, associate dean for academic affairs at Stanford’s medical school. “It’s an easier road now.”

Wren helped ease the way for younger surgeons, like transplant surgeon Amy Gallo, MD. By the time Gallo began her training at Stanford in 1999, she says gender was less of an issue in the profession.

Today, Gallo, 38, an assistant professor of surgery, balances her practice with her life at home with her husband, an accounting researcher, and two children – an infant and a toddler. She eats dinner most evenings with her family and is fortunate that her husband likes to cook and is willing to console the children in the middle of the night when she is called away to the operating room to transplant a new kidney or liver.

Maintaining a work-life balance “is definitely a work in progress,” she says, though “I have the family life I expected I would have.”

Gholami says it’s a matter of setting priorities and realizing that at times, “friend and family events will be missed. You just have to have a very good support network.” With the new work hours, she gets a day off a week and occasionally has time for herself. “I do work out. I do see my friends. It’s not a disastrous black hole where I disappear for seven years,” she says.

She has a boyfriend, who recently moved to this area to be closer to her, and says she sees marriage and family at some point in her future. But she knows it will not be an easy road. “I still think because of the difficulties of having families and children, it’s going to be tough. I’ve seen multiple examples of where it’s worked, but it takes someone special as a partner who understands. ... This is probably my biggest challenge, the constant struggle of balancing a career in academic surgery with my personal life.”

After her residency, Gholami plans to pursue a two-year fellowship in surgical oncology, ideally at an academic cancer center such as Memorial Sloan Kettering in New York, where she spent two years during her residency developing a breast cancer therapy. The treatment, a genetically engineered smallpox virus, has done well in preclinical testing, and she hopes to see it enter clinical trials, she says.

At the moment, her patients fuel her passion for surgery, the ultimate cure for many tumors. She recalls one young man who came in recently with an ailing appendix. He was fearful of surgery and left the hospital against doctors’ orders. He returned that same evening, feeling poorly, and apologized for leaving. He’d gone home to pray, he’d said, and had hoped his condition would improve. But it had become clear to him that surgery was his best road to recovery.

“There are certain things where you know surgery is the only way,” Gholami says. “That for me is the ultimate gratification.”

Max Aguilera-Hellweg, MD, started his photography career at 18 working in Rolling Stone magazine's darkroom and assisting chief photographer Annie Leibovitz. He has shot not only for Rolling Stone, but for publications including National Geographic, The New Yorker, Time, and Stanford Medicine magazine.