FALL 2013 CONTENTS

Home

Hello in there

Seeing the fetus as a patient

Gone too soon

What's behind the high U.S. infant mortality rate

The children's defender

A conversation with Marian Wright Edelman

Too deeply attached

The rise of placenta accreta

Labor day

The c-section comes under review

Changing expectations

New hope for high-risk births

Inside information

What parents may – or may not – want to know about their developing fetus

DOWNLOAD PRINTABLE

ISSUE (PDF)

Special Report

Changing expectations

New hope for high-risk births

by Julie Greicius

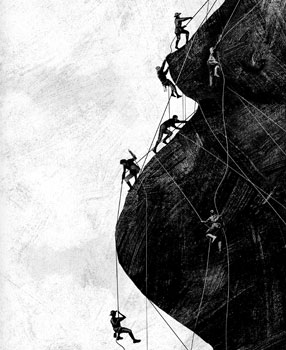

Illustration by Daniel Horowitz

On any given Friday, shortly after dawn, one or two dozen doctors and nurses gather in a darkened room on the first floor of Lucile Packard Children’s Hospital at Stanford. Over the course of an hour, a monitor at the front of the room displays the radiological scans of six or seven patients. Some have ill-developed bones; others have misplaced internal organs or malformed hearts. For each, the doctors and nurses — specialists across many disciplines — discuss the chances of survival and a plan of care, yet it will be weeks or months before any of these patients will even be born.

It’s clear that advances in fetal imaging techniques have increased the discovery of abnormalities before birth, allowing care teams to prepare for the mother’s and baby’s needs before, during and after delivery. For many prenatal diagnoses, the ability to address problems — either in utero or after delivery — has also made great strides. “But ensuring good outcomes from these advances depends on input from a diverse team of care providers and their tight coordination,” says Susan Hintz, MD, medical director of the Center for Fetal and Maternal Health at Packard Children’s, and a professor of neonatology at Stanford.

On a Friday in December 2011, attention in that darkened room at Packard Children’s focused on the image of a tiny pulsing heart — the heart beating inside Colleen Doria’s developing child. Colleen, 24 weeks pregnant, and her husband, Michael, both first-time parents, were at their home outside New York City, awaiting the outcome of that meeting with desperate hope.

A few weeks earlier, Colleen’s doctors on the East Coast had given her devastating news: Her baby’s heart had a hole in the wall between the two lower chambers, and there was no pulmonary artery. The baby, who would be named Teagan, had a complex heart malformation called tetralogy of Fallot.

One of the most common congenital heart defects, tetralogy of Fallot can be surgically repaired at almost any children’s hospital. But Teagan’s case represented the most complex scenario: Most tetralogy of Fallot patients have a narrowed pulmonary artery, the vessel that carries blood from the heart to the lungs; a small subset, of which Teagan was a member, lack it completely. To compensate, the fetus develops “collateral” vessels, scattered side branches that provide blood flow to the lungs. Before a child is born it’s impossible to know how many collateral arteries have developed, or how well they support lung function.

“Patients like Teagan don’t usually die at birth, but — when the condition goes undiagnosed or untreated — about half will die by the time they are a year old, and 90 percent will die by the time they are 10,” says Frank Hanley, MD, director of the Children’s Heart Center at Packard Children’s. “Because most institutions consider the absence of a pulmonary artery an inoperable condition, seeing this condition on a fetal echocardiogram would tell them that this child is doomed to a horrible, very short life. And they would counsel parents about ending the pregnancy.”

Talking with their doctors about their child’s prognosis was one of the hardest conversations of Colleen and Michael’s lives. “They told us our baby would probably never leave the hospital,” says Colleen. “Or she’d go into hospice and pass away. They said that even if she had surgeries, she would still have poor quality of life.”

After visiting heart teams at two hospitals on the East Coast, Michael, a New York City police officer, and Colleen, a special education teacher, weighed the decision to terminate the pregnancy.

“I would never judge anyone for making that choice,” says Colleen. “It just wasn’t the choice for us.”

Colleen’s doctors warned her that searching the Internet for information about her baby’s condition was likely to be fruitless and upsetting. But she got online anyway, and found a mother’s blog describing her own baby’s diagnosis of tetralogy of Fallot with the absence of a pulmonary artery. It also described the surgery her baby had received, a procedure called “unifocalization” developed and performed by Hanley at Packard Children’s.

“It’s the most complicated operation in the field of congenital heart surgery,” says Hanley, a professor of cardiothoracic surgery at Stanford. “You have to find the collateral arteries, wherever they may be, reroute them, bring them together, and actually create a new pulmonary artery by sewing them together. We’ve done about 800 of these with excellent outcomes, so I know there’s a 98 percent chance we’re going to be able to make a difference. We’re able to counsel a family when they get the prenatal diagnosis at 20 to 24 weeks’ gestation that there is not only hope for this condition, but the prognosis can be quite good.”

Over the phone, Hanley confirmed the Dorias’ baby’s diagnosis and gave them a very different picture of her future. “After hearing nothing but bad news,” recalls Colleen, “Dr. Hanley told us, ‘I feel encouraged that I would be able to help your daughter.’”

Finally, Colleen felt that her choice to continue the pregnancy was the right one. She and Michael decided she would give birth at Packard Children’s and have the baby’s heart surgery there as well.

That the Dorias had any choice at all was a wonder — and a measure of how far diagnosis and care for complex fetal conditions has come. Prenatal diagnosis of congenital heart defects like tetralogy of Fallot became available in the late 1980s. Before then — and even today, without adequate prenatal care — Teagan’s condition would have been discovered only after her birth, and perhaps only when it was too late. Doctors would have rushed to learn everything they could about the newborn and only then would have assembled the medical team needed. At Packard Children’s, the crucial coordination is provided through the Center for Fetal and Maternal Health.

“You need the integration — the human integration and the technological integration. What makes the difference is the breakdown of silos between disciplines,” says Yasser El-Sayed, MD, obstetrician-in-chief at Packard Children’s and director of maternal-fetal medicine and obstetrics at Stanford. “In isolation none of these variables can do the job.”

In other words, the right people need to talk to each other starting as early as possible in a high-risk pregnancy. Because of this, Packard Children’s has made weekly fetal-care meetings standard practice. These meetings assemble physicians, surgeons, radiologists, obstetricians, neonatologists, respiratory therapists, genetic counselors, neurologists, cardiologists, nurses, social workers — literally anyone who might have expertise relevant to a patient’s needs. For complex patients like Teagan, smaller meetings among care providers happen daily.

Colleen and her baby would need careful medical management in the weeks leading up to delivery and in the months and years to follow. Hanley planned to do Teagan’s surgery three months after her birth, when risks of lung and cardiac complications were lowest. As a congenital heart disease patient, Teagan would also need follow-up care at least annually for the rest of her life. But first, ensuring the best outcome meant coordinating a thousand small details — everything from securing insurance coverage and housing during their stay, regular communication with Colleen’s doctors on the East Coast, and creating a precise list of doctors, nurses and equipment to be at the bedside ready for any number of complications at the moment of Teagan’s birth.

One expert at managing those details is Stephanie Neves, administrative coordinator for Packard Children’s Center for Fetal and Maternal Health. Neves spoke with Colleen by phone several times a week until she arrived at Packard Children’s three weeks before her due date. Neves was also the point person for progress reports, echocardiograms and other updates sent at least weekly by Colleen’s obstetrician in New York. Neves then updated Colleen’s records at Packard Children’s and made sure all the doctors involved in her case had the same information.

And that was for just one mom. “Everyone on our team has a detailed list of the active moms we’re following,” says Neves, “which is about 75 to 85 women at any given time.” At least 40 percent of those women come from more than 80 miles away, making housing arrangements especially important. “The fetal-center team worries about all these details so the family doesn’t have to.”

‘She never spoke to us as though we should be scared. I could be a normal Mom. I thought: This is how other women must feel.’

Colleen Doria

While Neves took care of logistics and cross-country communication, genetic counselor Meg Homeyer gathered the results of the tests Colleen had taken at a New York hospital. “If there is a genetic component that we can identify, it helps us explain to families what to expect and plan for,” says Homeyer. The Dorias were lucky: Though tetralogy of Fallot is sometimes a consequence of DiGeorge syndrome, a widely variable, sometimes debilitating genetic condition, the test showed this was not the case for Teagan.

“We think about a complex fetal anomaly not just as a fetal problem, but as an issue for immediate post-delivery care and for childhood — what is best for the fetal patient, the baby and the child later on,” says Hintz, the center’s medical director. “It’s an enormously positive thing that we’re involved in,” says Hintz. “We’re helping to plan for the future of the family.”

In March 2012, the Dorias left a fresh snowfall and flew across the country to have their baby at Packard Children’s. Admitted right away for monitoring and testing, Colleen met Neves, who walked her to her appointment at the perinatal diagnostic center and then to consult with cardiology and neonatology specialists. The next day, Hintz met with the Dorias to plan for the birth and for Teagan’s care. Hintz also gave them a tour of all the settings for the birth and treatment — from labor and delivery, to the neonatal intensive care unit and the cardiovascular intensive care unit. In her room, Colleen met with a social worker, a care coordinator, several imaging technologists, anesthesiologists, intensive care nurses, and cardiologists, and her baby’s heart surgeon, all of whom helped her prepare for what was to come. “They made it so seamless,” says Colleen. “There was nothing we had to do except walk into the hospital that day.”

Counseling, preparation and ongoing support of parents are key factors in care coordination, says Hintz, because, no matter how significant a baby’s medical need may be, the parents are the most important people in their child’s life.

Members of the Center for Fetal and Maternal Health team have multiple conversations with the parents, says Hintz. “We really try to emphasize to families that if they have questions they can ask anything they want, even if we’ve already covered it.”

“Stephanie [Neves] understood how special the situation was for us,” says Colleen. “I could finally have a conversation with someone about my baby and the tone was normal. She never spoke to us as though we should be scared. All of that stress and all of the odds and ends that we’d have to worry about — she took that away. I could be a normal mom. I thought: This is how other women must feel.”

Unexpectedly, just a few days after Colleen arrived, she began having contractions. Since the baby’s position in the uterus was breech, delivery would be by caesarean section. In the delivery room were nurses, doctors and an anesthesiologist caring for Colleen, and a team from the NICU, including a neonatologist, neonatal nurse practitioners and nurses to care for Teagan’s immediate needs. In the NICU, cardiologists, a respiratory therapist, nurse specialists and others awaited Teagan’s arrival, ready with a ventilator in case she needed oxygen.

“Dr. Hintz had told me, ‘There’s going to be a million people in the delivery room and then, all of a sudden, the baby’s going to be delivered and then there’s only going to be a few people, because most will go with her to the NICU right away,” says Colleen. “They let me choose whether to have Michael stay with me or go with the baby. I wanted him to go with her.”

Teagan didn’t need the ventilator. Although she had no pulmonary artery, her body had compensated by developing major aortopulmonary collateral arteries to supply blood to her lungs. Until she was born, there was no way to know exactly how many. Teagan, it turned out, had lots of them. The concern, then, was not whether she was getting enough oxygen but whether she was getting too much.

The next morning, Colleen had recovered enough to go with her husband to visit Teagan in the NICU. She found her snuggled in an isolette with monitors tracking her heart rate, blood pressure and oxygen saturation. “She is one strong little girl,” one of the nurses told Colleen as she passed the baby into her mother’s arms for the first time.

After Teagan spent two weeks in the NICU, she was able to go home for three months. Her parents had been trained to care for her until the return for her heart surgery with Hanley.

“They showed us how to give her medications and how to put in her nasogastric tube,” says Colleen. Inserted through the nose and leading to the stomach, the tube would allow the Dorias to give their daughter medications and supplemental high-calorie formula. “And they told us, ‘You are not going to leave here unless you are 100 percent comfortable taking care of her.’ So we took her home, which was very scary. But we were very careful, and had lots of support from family and friends.” Teagan also had regular visits with a cardiologist in New York who kept a close eye on her progress and communicated with her care team at Packard Children’s.

The Dorias flew back to California in June. After Teagan’s 12-hour heart surgery — the standard duration of the complex procedure — Hanley gave them the happiest possible news. “He said there’s no reason she can’t live the normal life that every kid around her is going to have,” says Colleen. “She’ll play sports, go to birthday parties and school. There’s nothing she won’t be able to do.”

“It’s an exciting time,” says Hintz. “There are things we’re doing now for patients that we could not have done even a few years ago. Prenatal testing for life-threatening metabolic diseases, for example, allows us to diagnose early, pretreat intravenously during labor and delivery, and treat the baby immediately after delivery. What we’re really trying to do is get as much information as possible before the baby is born so that we can get the best teams and treatment in place for the baby.”

It worked for Teagan, now a thriving 18-month-old. “I’m not gonna lie,” says Colleen. “She’s really cute. When I take her out, her face just lights up. Last week we visited a restaurant that had a sandbox. She walked right up and waved, like she’s saying, ‘Hi everyone! I’m here!’”