In Brief

Cadaver 2.0

Testing a virtual dissection table for teaching anatomy

By Tracie White

Photography by Norbert von der Groeben

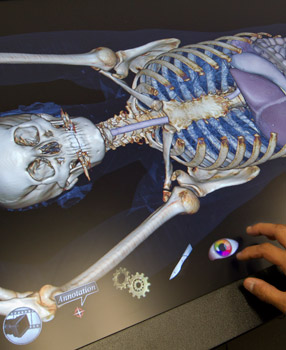

So how does this work, exactly? The dissectionist’s usual scalpels, forceps and probes won’t do the job here. Instead students peel away layers of imaged flesh and bone by tapping and swiping the touchscreen tabletop.

“You make the diagnosis,” says the anatomy instructor, looking up expectantly at his students. The handful of undergraduates gather around the newest anatomy teaching aid, a life-sized, iPad-like dissection table with an image of a young woman’s injured shoulder.

Peering intently at the screen, the students can’t resist touching it. With a swipe of the forefinger, they zoom in on the image. Then zoom out. One touch, and the virtual shoulder rotates. Another touch, and the muscles disappear, leaving just the bones. One more touch and the bones dissolve, leaving the circulatory system behind.

“I’ve never seen anything like it,” says Meghan Bowler, 21, a junior bioengineering student from Boston.

Only an hour or so earlier in a nearby classroom, the instructor, Sakti Srivastava, MD, associate professor of surgery and division chief of clinical anatomy, had presented a lecture on the anatomy of the upper limb using visual aids — illustrations and diagrams — and then led the group to the lab for hands-on education using cadavers, some 3-D dissection photos and the new technology, essentially a virtual dissection table.

With the table, Silicon Valley engineers have now joined a long list of doctors, artists, photographers and other technology innovators seeking the best way to explore and learn about the anatomy of the human body.

The new virtual dissection table takes advantage of 20th-century technological advancements in imaging, such as X-rays, ultrasound and MRIs, and combines them for use in a 7-foot-by-2.5-foot screen. At Stanford, the table is being tested as a way to further enhance that age-old teaching method — the dissection of human cadavers.

“We want to see what the educational value of this resource, this tool, might be.”

“The virtual isn’t the same as the real,” says David Gaba, MD, associate dean for immersive and simulation-based learning. “What we want to do is leverage the best of both. It’s not really, ‘Is one better than the other?’ Rather it’s, ‘What can we do with the two combined?’”

Its creators refer to it as something of a reusable cadaver, with the added benefit of allowing users to easily explore hard-to-reach parts of the human body.

The table, which made its debut on campus in April, is on loan from Anatomage, a San Jose-based medical technology firm, to the anatomy division at the medical school. Faculty are experimenting with its use as a possible teaching aid for everyone from undergraduate anatomy students to medical students, residents and even patients.

“We want to see what the educational value of this resource, this tool, might be,” Srivastava says. “Does it complement the cadaveric work of our students?”

The $60,000 device is part of a new wave of technology that makes possible interactive displays of the body using real-life images. The touch screen — created by placing two LCD screens together horizontally — allows users to investigate a realistic visualization of 3-D human anatomy and to delve inside the human body. CT scan images are augmented with 3-D modeling and annotation explaining what the viewers are viewing. (One body-sized LCD screen would have had to be custom-made, and thus prohibitively expensive.)

The images morph from soft tissue to hard tissue. The tissue can be sliced much like actual tissue on cadavers in the dissection lab next door, but no knife is needed — just a single slide of a finger will do. Then, with the press of a button, the entire body is restored instantly.

“The idea is you can build the body part by part,” says Paul Brown, DDS, consulting associate professor of anatomy.

Students using a virtual cadaver can remove entire organ systems with a finger tap.

The concept for the table sprang to life about a year ago during an informal conversation between Brown and Jack Choi, PhD, the CEO of Anatomage. Choi happened to be visiting Stanford to provide a tutorial on software in use by the medical school. Brown mentioned that he’d been researching and working on the idea of bringing such a table to Stanford for teaching purposes but had failed to find a way to have one made that would be affordable.

For about two years, Brown had scoured the globe for hardware and software vendors to build such a table. His search led him from the University of Illinois, where engineers were working on a prototype of a life-sized digital video screen, to Sweden where a company has built a virtual autopsy table. But neither was quite right for the classroom use he envisioned.

After listening to Brown’s idea, Choi said, “Oh, I can build one of those,” Brown recalls. So Choi put several engineers to work on developing the table.

“Finally, it’s ready for prime time,” Brown says. The Anatomage table is designed to be used for teaching anatomy on various levels of complexity.

“Each image brought up will have a reason for being there. It’s not meant to be just pretty, but extremely useful as a teaching tool,” says Brown. “There are so many different normal variations in human anatomy and then there are all the different pathologies.”

Four faculty in radiology and anatomy are building a searchable library of digital anatomical images based on CT scans, MRI and ultrasounds of the human body that could be used with the table as well as other educational technologies. The Stanford researchers know of no resource comparable to what they’re shooting for.

With access to such a library, a virtual dissection table could include many anatomical variations and pathologies — from tumors to fractures to cystic fibrosis. Anatomy professors at Stanford and other schools could use the image library to develop a wide variety of lesson plans.

Srivastava and the three others who are working on the imaging library — called the Searchable Digital Anatomical Library — hope to have it licensed through Stanford’s Office of Technology Licensing. Their goal is to make it available to other educational institutions, nonprofits and companies such as Anatomage. Any financial proceeds from the library would be divided among Stanford, the faculty and their departments as is typical for technology transfers by universities.

The first students to work with the table were in the new undergraduate bioengineering anatomy course taught by Srivastava. The day’s instruction began with a traditional lecture focused on the anatomy of the shoulder and the arm: the veins, arteries, nerves, bones, muscles. Then students walked over to the lab.

In one room was the traditional dissection lab. It was filled with rows of the medical students’ cadavers, each covered by a blue tarp. Two were uncovered: human arms were on display. With gloved hands, teaching assistants picked up and pointed out the ulnar artery, the brachioradialis muscle — each anatomical piece described and illustrated previously in the lecture hall.

“What artery is this?” asks a teaching assistant, separating one vessel from the other.

“The ulnar,” the group says.

“And this?”

“The radial.”

When they were finished, the students moved to the room next door to view 3-D images of the shoulder and chest from the world-renowned Bassett photographic collection of human dissection. And then on to a third lab room where the virtual dissection table was open for class.

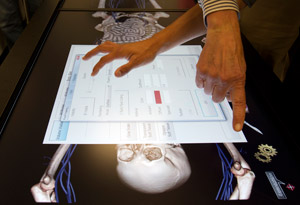

At the virtual dissection table, Srivastava asks the students for a diagnosis of the shoulder problem.

“The humerus is out of the socket,” Bowler answers.

“Right, it’s a complete dislocation,” Srivastava says. “Now, rotate the image a little bit. You can see there are smaller, fractured sections. You can predict the direction of the force that caused the dislocation. This is a rare variety. The patient comes in like this,” he says, holding his arm straight up in the air.

Then, he reiterates the anatomy that he described in the lecture hall: “This is the brachial artery. It divides into two.”

On to the elbow. “I want you to see this little piece of bone, the medial epicondyle. See that groove there? The ulnar nerve — that’s the funny bone — that’s where that sits. See the ulnar artery?”

Later, Srivastava says his experiences with the table are encouraging. “The virtual dissecting table affords new ways to see and interact with the same anatomy, as well as providing access to a collection of normal variations and abnormal pathologies,” he says. But it will take some time to determine how widely it will be used on campus in the long run, if at all.

Viewing 3-D photos of real dissections.

After working with the table for a few weeks in anatomy lab, bioengineering student Bowler is still impressed. “As a modeling tool and a tool for teaching diagnosis, I think the table holds great potential. It possesses the unique ability to allow us to look at the same body at different layers, with different features present and missing,” Bowler says. “But I have personally found the cadavers most helpful in lab because they allow me to inspect the muscles and bones of a real specimen — nothing is approximated.”

For her at least, the cadaver is still the best learning tool, because, well, it’s the real thing.

E-mail Tracie White

Web Extra

Bioengineering students try something new