Special Report

The woman who fell to Earth

A love story

By Ruthann Richter

Photography by Misha Gravenor

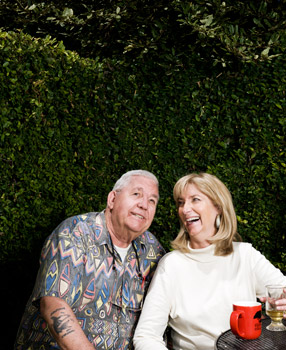

Gary Fairchild and Deborah Shurson

The April morning dawned clear, with the winds relatively calm and the air freshened by weeks of heavy rains. Thirty-year-old Deborah Shurson, tall, blonde and willowy, strapped nearly 100 pounds of gear on her 118-pound frame and stepped into the Cessna 206 on that day in 1982 when she; her husband, Randy; and two other friends would be carried 2,600 feet into the air.

Randy was first in line to jump, and he prepared by dangling his legs over the edge of the aircraft. He then leapt into the void, his arms spread-eagled and his back arced, the wind full force in his face.

“See you below,” he yelled to Deborah as he flew through the air. Five seconds into his fall, the static line engaged his chute, which opened above. Randy clutched

the handles around his shoulders, terror in his throat, resolving never to skydive again.

He landed in the drop zone at the Antioch, Calif., airfield with a thud when he

heard screams and turned to see Deborah, her partially opened white chute wrapped around her like a shroud as she streaked toward the ground. Her main chute had never opened, and she was frantically clawing her way to her reserve chute.

Deborah’s parents, who had brought a picnic lunch, stood paralyzed as they watched her in freefall at 125 miles per hour, then saw her disappear behind a hill in a little mushroom cloud — her reserve chute opening too late.

Randy, a trained paramedic, ripped off his pack and raced to Deborah, pausing briefly to pray since he knew she was gone. “Please God, accept her,” he said under his breath.

He arrived to find Deborah unconscious, her breath labored, like a primal gasp one takes before giving up on life.

Snowball in hell

As the doors flew open to the emergency room at John Muir Medical Center in Walnut Creek, Calif., neurosurgeon Paul Chodroff, MD, kicked aside a crash cart to clear a path for the gurney bearing Deborah’s shattered body.

She had already been resuscitated twice at Antioch’s Delta Memorial Hospital, and the scans there showed a staggering array of injuries: a punctured, collapsed lung that was leaking blood, a bruised heart, 14 or 15 broken ribs, a broken breastbone and ruptured spleen.

Her pelvis was fractured, as were both of her legs, and her right ankle had split off altogether. Her right shinbone had penetrated 12 inches into the earth. Most worrisome, Deborah was in a coma, with diffuse injuries to her brain and signs of contusion to her brain stem. Some of these injuries alone were life-threatening; taken together, they presented a grim prognosis.

Chodroff, her lead doctor, later likened her odds of survival to a “snowball in hell.” He told Deborah’s family that he could keep her alive for the next three or four minutes but couldn’t promise anything after that.

“He took us all aside and said, ‘Don’t expect her to be alive tomorrow,’” recalls Deborah’s father, Dave McCahon, choking back tears at the memory of that time. “He said, ‘If she does live, she will be a vegetable. She will not walk or talk.’”

Clinging to life

In the intensive care unit, Chodroff, a thin, intense man with glasses, stood at the foot of her bed like a traffic cop directing the myriad medical specialists and nurses who had been called in to try to save her life.

Without oxygen, Deborah’s brain would survive only minutes, so his first job was to keep her breathing despite critical damage to her lungs and chest. Artificial breathing support — a respirator and chest tubes — had been installed and he turned up the pressure. Miraculously, Deborah lasted through the night.

For weeks, her condition remained precarious, her life suspended in a limbolike state. Randy slept at the hospital, and with Deborah’s parents, brother, sister and sister-in-law kept a vigil at her side, enlisting church friends throughout the world to pray for her, playing tapes of favorite pop songs, reading letters from friends and keeping up a regular chatter in hopes of reviving her dormant brain. The nurses braided her long, blonde hair and placed it on her head like a crown, giving Deborah the aura of a sleeping princess.

“She looked beautiful, and we thought, she’s just going to wake up any moment,” recalls her sister-in-law, Robin McCahon.

Against all odds

Deborah wasn’t awake but, incredibly, she was still alive.

“When you hear these amazing stories of survival, they suggest that, among other things, these may be individuals who mounted an optimal fight-or-flight response during life-threatening stressors,” says Firdaus Dhabhar, PhD, an associate professor of psychiatry at Stanford who studies human resilience in the face of stress.

He speculates that while Deborah was zooming to Earth, her stress physiology and immune system were actively priming her for the fight ahead.

In an optimal stress response, the body initially releases a flood of immune cells into the blood, which subsequently lodge in the skin and other sentinel areas to defend against wounds or infection, he says. If there is an injury, this response enables larger numbers of immune cells to travel to the damaged area to help promote healing. In Dhabhar’s studies with surgery patients, he has found that those who effectively launch this short-term physiologic response have significantly better recoveries than those who don’t. But a primed immune system could do only so much.

Deborah’s condition deteriorated during those first weeks. Despite a tube-delivered daily diet of 6,000 calories — about triple her ordinary intake — she was wasting away. Suspecting a hidden infection, orthopedist Doug Lange, MDMD, took her into the operating room in week three, opened up the cast on her right leg and found jammed inside her shin bone several inches of dirt and clay from her crash landing. He also found a massive infection. He carefully cleaned and pinned the wound.

From that day on, Deborah grew stronger. About a week after the leg wound was cleaned, a friend was massaging her feet and promising her chocolate chip cookies when Deborah’s eyes flew open and she seemed to hold her gaze. She was awake, showing the first signs of consciousness, vaguely alert to movements around her.

On day 51 at the hospital, Deborah hit her biggest milestone. Perched in a hallway in a wheelchair, she looked up at Chodroff and said: “Hi, Doctor.” She could speak. Randy gleefully lifted up the doctor and swung him around as they both laughed and cried. Over the next weeks, Deborah began to speak more but she was far from recovered. She couldn’t follow commands and had forgotten basic things, like how to chew her food, which padded her cheeks. She did not recognize Randy, her husband of six years.

Her dramatic story and her determination to live resonated through the halls. Deborah had become a star patient, and word of her revival quickly spread. Her final days at the hospital were filled with celebration. The staff threw a party with cake, an honorary nurse’s cap for Randy and a diamond bracelet for Deborah. Still, when she left the hospital, three months after the accident, she was in a wheelchair, both legs in a cast, unable to take a step. Her speech was limited to a few dozen words. She was childlike in her behavior, smiling but unable to understand why there was so much fuss around her.

She had survived, in part a result of excellent medical care, and in part because of her fantastic luck — and the mud.

“Had the winds blown her just 50 feet to the left, she would have landed on an asphalt road. Had she blown another 50 feet to the right, she would have landed in a lake and drowned. By the grace of God, we’d had 10 weeks of solid rain, and the ground was saturated. She went 12 inches into the mud,” recalls her mother, Doris McCahon, who refers to Deborah as “our miracle girl.”

Her gender also may have been on her side. Studies suggest high progesterone levels in women, which occur during certain days of the menstrual cycle, protect their brains during trauma.

And there was another factor, one that can’t be quantified: Deborah’s determination.

“A lot has to do with the person — their underlying drive in life and how much of that drive is preserved after the injury,” says Jeffrey Englander, MD, chair of physical medicine and rehabilitation at Santa Clara Valley Medical Center in San Jose, Calif.

Deborah certainly was bent on regaining her independence. “I remember one of the doctors saying to me if I ever walked again, it would be years down the road,” Deborah recalls. “I remember the doctor looking me in the eye and I said something like, ‘Watch me.’ He threw up his hands and said, ‘I give up.’ I just grinned. That’s me — I’m a fighter from the word go.”

But it was not a fight Deborah could wage alone, and she would find help from an unexpected source.

The long journey begins

When Deborah arrived at the brain injury rehabilitation unit at Santa Clara Valley Medical Center, her legs still in casts, she was able to stand only with help on both sides, her shoulders stooped over her slender frame.

“I remember one of the doctors saying to me if I ever walked again, it would be years down the road. I remember the doctor looking me in the eye and I said something like, ‘Watch me.’”

But brain damage was what most incapacitated her. She spent her next three months at the San Jose hospital relearning the basic gestures of daily life. There she devoted six hours a day to therapy, practicing baby steps in the gym and regaining the skills needed to care for herself — how to wash her face and button her blouse, how to lift a spoon to her mouth and swallow her food, slowly repeating the motions to get them right. At first, her speech was so poor that she communicated mostly with nods or hand gestures. In therapy, she began to recapture lost words and phrases. Her caregivers taught her to hold a pen and form letters on a page. Her short-term memory was impaired, so she obsessively wrote things down in a barely legible scrawl, her notepad always at her side. Eventually they taught her what it meant to write a check, though her understanding of financial matters was elusive and remained that way for years. She didn’t remember conversations or who had visited her moments before. But she was resolved to get better.

For patients, “This is probably the most devastating injury of their life,” says Englander, whose unit is one of 16 nationwide designated by the National Institute on Disability and Rehabilitation Research as model facilities. “They have to say, ‘I’m a differently capable person now and I choose to make the best of where I am and work on that.’ And that’s a big step for people to realize that.

“They’re beginning their journey, and the journey takes years,” he adds. “It’s a tough journey — it really is.”

The extent to which brain-injured patients recover depends on their type of injury, such as a stroke, tumor or trauma; the depth of the injury; and whether it affects both sides of the brain, says Thao Duong, MD , the unit chief and vice chair of physical medicine and rehabilitation at Valley Medical. If a patient with traumatic brain injury is in a coma of longer than four weeks, the likelihood for a good recovery decreases significantly, she says. By all these measures, Deborah’s prognosis was poor.

Brain-injured patients typically show the most progress in the first year or two; after that their progress is typically slower, though there is still the possibility of some improvement, Englander says. “People can take something very important to work on, whether it is walking or communication or performing a favorite activity, and they can learn not only from professionals but from peers,” he says.

“TBI patients are very motivated,” says Odette Harris, MD, MPH, director of the polytrauma unit at the Veterans Affairs Palo Alto Health Care System and associate professor of neurosurgery at Stanford. “What binds them all is that those who do survive tend to be very driven.”

Home

After three months, Deborah left Valley Medical, returning with Randy to her Los Altos home and an enthusiastic greeting from her golden retriever, Charlie.

She continued physical therapy: Within months she had discarded her walker and crutches and was tottering around unaided, determined to be independent. But her cognitive abilities were limited and she had the emotional maturity of a child.

“The doctor told us she would go back to infancy and we would have to teach her everything along the way,” says her mother. “That, for Debbie, was extremely frustrating.”

At home, she was depressed and withdrawn, sometimes lashing out. Her speech was slurred and her voice hoarse, damaged by the tubes in her throat. “She could sit down and have two eggs on a plate and eat them, and if you asked her what she had eaten, she couldn’t tell you,” Randy says.

“The doctor told us she would go back to infancy and we would have to teach her everything along the way. That, for Debbie, was extremely frustrating.”

Asked about this time in her life, Deborah recalls little, other than her occasional walks with Charlie and her feeble attempts to tidy up the house. “I felt like I was in a fog. I would keep blinking and thinking it would get clear, but it never got clear,” she recalls.

Her transformation into a dependent person was a challenge for all those around her.

Deborah and Randy, who had met as college students at Chico State, had been leading fast-track lives. Deborah, a synchronized swimmer and former “Miss Congeniality” at San Carlos High School, had been an up-and-coming commercial interior designer. Randy was acting captain in the Menlo Park Fire Department. Both fitness buffs, they had taken a trip to Lake Tahoe just before the accident, hitting the difficult black-diamond ski runs. They were at the top of their game, with plans to remodel their three-bedroom home and start a family.

But now Randy was confronted with a strange new person in his life, the change in Deborah like a “Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde,” he says.

Six years after the accident he and Deborah divorced, an unfortunately common side effect of brain injury, experts say. “To this day, it still hurts me,” Randy said years after the accident. “I still have a lot of grief. I avoid Deb because of the grief I have over the loss of her.”

The couple sold their home, and Deborah moved to an apartment with a roommate whom she found through her church, “a motherly type” who helped keep an eye on her. She wasn’t able to work in interior design, and her old friends, seeing a different person, abandoned her.

Deborah’s parents, who were in the nursery business, helped her find a job at a local floral shop, where Deborah used her skills as a designer to make floral arrangements. Later she got jobs at a health food store and at Safeway, where she worked as a bagger until the pain of standing on her right leg made it impossible to continue. She was struggling.

Ten years after the fall

At Foothill College in Los Altos Hills, Deborah at 40 was hunched over a computer in a class for disabled students, trying to make sense of a game called Find the Keys, which challenges a player’s organizational skills.

She had already taken every class for the disabled at Cupertino’s De Anza College and had just started at Foothill, still not quite having mastered the basics. To all appearances she was physically recovered but she still read one word at a time rather than full phrases, and her writing looked like chicken scratches, she says, embarrassed to see it today. She signed up for what she calls the “bonehead” classes.

“The teachers would lecture, and some of it would go over my head, and it was hard for me to write things down. I would get bits and pieces. It was hard. It didn’t come easily,” she says.

“I was heart-broken. I had just built this beautiful house. My business was going well. I was in a good part of my life. I had sailboats and the fancy cars, and one day it’s all over.”

One day, she looked up to seek help from the instructor, and saw standing there a tall, burly man with wide glasses and a stutter. Actually, he was a classmate, 53-year-old Gary Fairchild, who was only too happy to help the attractive blonde. He and Deborah, it turned out, had much in common.

Gary had been a successful real estate developer when, while sitting in his office, he felt his head begin to ache. As he reached for an aspirin, he shook uncontrollably and felt as if his head were exploding. His son-in-law rushed him to Kaiser Permanente Medical Center in Redwood City, Calif., where he was diagnosed with a relatively uncommon congenital defect known as an arteriovenous malformation.

AVMs are a tangle of thin-walled vessels that can pop at any time, causing significant bleeding and stroke. In a 10-hour surgery, doctors removed the affected area of Gary’s brain, a lemon-sized section of his parietal lobe.

Gary woke up in the hospital after three weeks. A week later, he returned to his $2 million home in Los Altos Hills a changed man.

Once the fast-talking life of the party, his speech was garbled. His vision was impaired, and he walked into walls. He couldn’t find his way beyond his own driveway. He threw things and raged in frustration. He suffered such frequent seizures — a common side effect of his condition — that the local paramedics came to know him by his first name. At Foothill, he sat on a bench every day in the green expanse of the quadrangle, head in hands, and cried.

“I was heartbroken,” Gary says. “I had just built this beautiful house. My business was going well. I was in a good part of my life. I had sailboats and the fancy cars, and one day it’s all over, and you can’t get it back. Once the brain goes, it goes. If I hadn’t had all the mentors — all the people who helped me — I would have killed myself.”

In Deborah he found a kindred spirit. “She was lost emotionally. She didn’t fit in and she knew she didn’t fit in,” he says, as Deborah nods assent.

The two began meeting for lunch on campus as they sat in the quad, gazing at the shapes of the clouds, imagining golden retrievers in the sky. Deborah was bewildered by the Foothill campus, where all the red-tiled, Mission-style buildings looked alike, so Gary taught her some tricks he’d learned: follow the path to the yellow fire hydrant and turn right to find Building L, where their speech classes were held.

They went out on their first official date, riding their bikes to a deli at the Stanford Shopping Center. There Gary confessed that he still loved his wife. “OK, we’ll keep it cool,” Deborah told him.

But Gary’s wife had had enough. She was no longer able to cope with Gary’s erratic moods and outbursts, dependency and daily seizures. One morning at 7:30, she called Deborah to ask if she would be willing to rent Gary a room in her apartment. Gary was devastated, as he realized his marriage of 31 years was over.

He moved in with Deborah, and they soon discovered they had remarkably complementary abilities.

“I like to joke that between the two of us, we have one brain,” Gary says.

Gary had lost the vision on his left side, so Deborah protected his left flank. He also had a severe spatial-visual defect and easily lost his way, so Deborah stepped in to try to help navigate. When Gary was at a loss for words, Deborah helped complete the sentence. But when Gary’s speech returned, Deborah, herself mildly speech-impaired, often would turn the conversation over to him.

“What he didn’t know, I did, and vice versa,” Deborah says.

Both had short-term memory problems that hampered their ability to read books or watch movies, but that disability proved to be an asset in the relationship.

“Both of us forget things, so when we get into an argument, sometimes we just forget what we’re arguing about,” Gary says.

Together Deborah and Gary began reaching out to others with brain injuries, participating in a peer support group at Valley Medical for patients and families struggling through the early recovery phase. “Many people told us we were an inspiration to them — it gave them the hope and the drive to go on,” Deborah says. Deborah also got a job at Foothill College as a teaching assistant in the disabled students program, while Gary volunteered to help students in the pool during rehabilitation therapy.

“It made my heart feel good to know I could help,” Deborah says of the Foothill job, recently felled by budget cuts. “I was once in their shoes. I had been there and done that.”

Lucky in love

The injuries that had kept Deborah and Gary so isolated from others became a source of comfort and renewal.

“What alienates you from some people can be a bond with someone who has shared losses. I see this time and time again,” says David Spiegel, MD, professor of psychiatry and behavioral sciences at Stanford. “When you are injured, you automatically feel excluded from the rest of the world. But the wonderful thing about this kind of mutual support is you’re now among people with the same problem, and you feel accepted and appreciated. You have this instant sense of feeling oddly normal. So something genuinely good has come out of a bad situation. You have learned how to cope and you can use that knowledge to help other people with similar problems.”

And social support can not only be psychologically but also physically beneficial. Spiegel demonstrated the physical value of social support in a widely cited 1989 paper in the Lancet that showed women with advanced breast cancer randomly assigned to group therapy lived 18 months longer than those who had standard medical care alone. This finding was reaffirmed recently in two major studies, one in the journal Cancer and another in the New England Journal of Medicine. Both found that social support prolonged the lives of patients with breast and lung cancer, and while these studies were restricted to cancer patients, there’s reason to believe they could apply to others as well, Spiegel says: “Social support is good for your health.”

Now 18 years together, Deborah and Gary are inseparable. They love to travel — though they need a third person to come along to help them find their way. They love to socialize, especially when food is involved. They love staying fit. And they even enjoy the daily work to improve their cognitive skills. Gary begins his day seated at the computer in the living room of their Los Altos condominium, located in a turreted, red-brick building they call “the castle.” He tracks flashing figures on a screen to improve his vision, completes reading comprehension exercises, and plays a counting game — routing through a jumble of numbers to pick out one through 50 in order.

“I do it before I drive because it gives me confidence that my brain is engaged,” he says. But he still never drives without Deborah at his side. “She’s like having another set of eyes in the car, although she doesn’t always remember the points of navigation either.”

“Between the two of us, we figure it out,” Deborah says, laughing that their adventures are sometimes “like the blind leading the blind.”

They serve as a constant source of support for each other. “Deborah has been my angel. She’s been there for me when I’m down and when I’m up,” Gary says. Deborah calls Gary “my rock of Gibraltar.”

“We love in such a special way — it may not always be romantic, but it has a lot of …,” he stopped, searching for the right word. “Empathy,” Deborah says. “Compassion,” Gary adds. “And meaning,” she says.

Now approaching her 60th birthday, Deborah is radiant, with no physical signs of her staggering injuries other than a gouge in her right shin. She has a lift in her right shoe to compensate for the bone loss, and walks 5,000 steps every day around her neighborhood to maintain her mobility. She is ever upbeat, cherishes her time and calls her life fantastic.

“I often ask myself, ‘Why did I live?” They gave me less than a 2 percent chance, and I proved them all wrong,” she says. “I’m stubborn. It wasn’t my time yet. I have a lot of people to see and meet. I have too much living to do.”

Here's help

Brainline

A comprehensive website with information on prevention and treatment, as well as management of day-to-day issues for those living with brain injury.

Brain Injury Association of America

The largest U.S. brain injury advocacy organization, this group lobbies for greater resources and research and disseminates a wide range of information on symptoms, treatment and other issues related to brain injury.

The Center of Excellence for Medical Multimedia

Developed by the Defense and Veterans Brain Injury Center, this includes a guide for family caregivers.