FALL 2011 CONTENTS

Home

Game Change

On the verge of a revolution

Inside the labs

Highlighting recent Stanford cancer research

Cancer's biographer

A conversation with Siddhartha Mukherjee

The unexpected

Cancer during pregnancy

After cancer's cured

What's left to heal?

Make your own cancer diagnostic test

It's easier than you think

DOWNLOAD PRINTABLE

ISSUE (PDF)

Plus

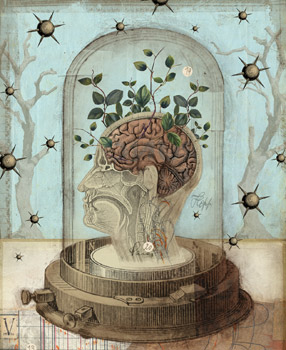

Old brain,

new tricks

What blood’s got to do with it

By Bruce Goldman

Illustration by Lars Henkel

Count Dracula may have been bloodthirsty, but nobody ever called him stupid. If that practitioner of what you could call “the Transylvanian transfusion” knew then what we know now, it’s a good bet he was keeping his wits as sharp as his teeth by restricting his treats to victims under the age of 30.

“Friends don’t let friends drink friends,” read the first slide of graduate student Saul Villeda’s PowerPoint presentation as he kicked off his PhD thesis defense on Dec. 3, 2010. Considering what he was about to tell the audience, this was probably a prudent admonition. Working in the lab of associate professor of neurology and neurological sciences Tony Wyss-Coray, PhD, Villeda had helped uncover a relationship between blood and brain that may have huge implications for all of us non-vampire types who grow older day by day.

Aging takes a toll on all tissues, but its wrath is reserved especially for tissues with low regenerative potential — for instance, the brain. What Villeda and Wyss-Coray found — in mice, to be sure — was that old blood has a detrimental effect on the brain. The hope: We humans might someday be able to rejuvenate our own aging brains with as-yet-unidentified factors circulating in young blood.

Extraordinary though this may sound, it’s not without support. The research literature shows that muscle and liver tissue, and blood itself, renew themselves more easily in the presence of young, versus old, blood.

It seems that something in blood influences stem cells, those acclaimed protean spheroids resident in most of our tissues. Depending on cues they get from their immediate surroundings, stem cells can variously hibernate, multiply or produce differentiated daughter cells that renew or augment tissues in need of bulking up.

The brain is the body’s most heavily vascularized organ, boasting a huge amount of surface contact with the maze of blood vessels that run through it. But liver and muscle have no barrier separating them from the circulating chemistry set that is our blood. The brain does. It is cordoned off from the circulatory system by a tight curtain of barrier cells, the better to keep it from crashing every time you nibble on a Twinkie, boosting the glucose levels in your blood to the high heavens, or get an infection, triggering all kinds of molecular mayhem in the blood.

However, it’s become clear that, blood-brain barrier be damned, certain blood-borne molecules whose levels rise with increasing age can get into the brain and mess up its ability to generate new nerve cells along with its capacity to do its job.

Wyss-Coray’s team has pinpointed a few of these molecules in mice and is on the verge of identifying other blood-borne molecules that have an opposing, brain-rejuvenating, effect but whose numbers diminish in aging blood. There are hints that some of them affect human brains the same way.

“We’re not talking about a disease,” Villeda says. “This is normal aging, the one thing none of us can escape from. This affects every single person on Earth. We’re all getting old. There might be ways of changing that. That, to me, is just wild.”

The substances suspected as damaging our brains’ ability to form new nerve cells are immune-signaling molecules, produced in excess as we age. Can we protect ourselves from these detrimental effects?

Can we stay smarter for longer?

Ask a mouse

Mice and people are different, but we have a few things in common. They like cheese, we like cheese (well, most of us do). Human and mouse brains are a lot alike, too. The same basic building blocks — nerve cells and supporting glial cells — assemble into similar brain structures in both species.

It’s now understood that the adult human brain is capable of producing new nerve cells, which are key to forming certain types of new memories and, therefore, to new learning. This is possible because the brain, contrary to the conventional wisdom of two decades ago, has its very own stem cells. These precious cells are not randomly distributed throughout the brain, though. Both mouse and human brains have been found to harbor stem cells — and to produce new nerve cells — in just a couple of specialized niches, very close to blood vessels. Here, stem cells can quietly incubate or, given appropriate cues, replicate or differentiate.

Alas, the numbers and activity levels of stem cells in the brain diminish with increasing age. So do certain mental capabilities, such as spatial memory: An example in humans is remembering where you parked the car. If you’re a mouse, it could be recalling the whereabouts of an underwater platform you can perch on so you won’t have to keep swimming in order to keep your nose above water.

In 2005, professor of neurology and neurological sciences Thomas Rando, MD, PhD, published a study in Nature showing that stem cells in the muscle and liver tissue of mice thrived when exposed to younger mice’s blood. To demonstrate this, Rando’s team used a surgical technique to join the circulatory systems of two mice. Connecting a young mouse to an old mouse this way let Rando and his colleagues measure the direct effects of exposure to young blood on a living older animal’s tissues, and vice versa.

Rando also noticed changes in the number of stem cells in mice’s brains, mirroring those seen in muscle and liver. But spending the time to get enough supporting data to include these findings would have held up the study’s publication. So he omitted them from the published work.

He did, however, tell Wyss-Coray about it. That conversation set in motion a five-year effort whose outcomes were published in a Nature study this fall. Villeda was the first author, Wyss-Coray the senior author and Rando one of its co-authors.

Wyss-Coray was already interested in blood-borne factors and the brain. In fact, he was on his way to publishing an article in Nature Medicine about proteins whose concentrations in blood correlate with the onset and progression of Alzheimer’s disease and that might therefore allow an early diagnosis of the disorder.

Blood-brain barrier notwithstanding, the brain is affected by the so-called pro-inflammatory molecules secreted into the blood during the immune system’s response to viral and bacterial infections. “Sleepiness, fuzzy thinking — these are behaviors generated in the brain,” says Wyss-Coray.

Still, he says, “the prevailing theory at the time was you had to be insane to pursue the effects of blood-borne factors on the brain. Saul was crazy enough to do it.”

Villeda, a new arrival in the Wyss-Coray lab, came with the right tools for the job. He had been looking at stem cells in the brain during a prior hitch in the lab of associate professor of genetics Anne Brunet, PhD.

They plunged in, first by examining the brains of mice of different ages and confirming earlier reports by others that the older the mouse, the fewer new nerve cells its brain was generating in a key area called the hippocampus.

Next, Rando taught Wyss-Coray, Villeda and their peers the technique for connecting mice’s circulatory systems. They compared the numbers of new nerve cells being generated in each partner of several old/young mouse pairs with the numbers they had previously observed in solitary mice of various ages.

“We’re all getting old. There might be ways of changing that. That, to me, is just wild.”

Sharing blood with a younger mouse seemed to rejuvenate older partners’ brains. Young partners of old/young pairs generated fewer new brain cells than unpaired young mice did, and old young/old mouse partners generated more.

“We saw a threefold increase in the number of new nerve cells being generated in old mice exposed to this ‘younger’ environment,” says Wyss-Coray.

Clearly, something in the older mice’s blood was affecting younger mouse-pair partners’ brains, and vice versa. Whatever that something was, it wasn’t cells. Wyss-Coray’s group showed, for example, that just injecting plasma (the cell-free fraction of blood) from old mice into young mice’s tails produced many of the debilitating effects of an out-and-out circulatory hook-up to an old mouse.

Next, Villeda, Wyss-Coray and their labmates checked for age-related differences in the levels of 66 immune-signaling chemicals in mouse blood. They found 17 whose amounts rose with age. Six of these substances also increased in younger members of young/old mouse pairs, compared with levels in mice whose circulatory systems hadn’t been exposed to old blood.

One of the molecules they identified was eotaxin, a small protein that attracts immune cells called eosinophils to areas where it has been secreted by other cells. In blood and cerebrospinal fluid drawn from healthy people between the ages of 20 and 90, eotaxin levels increased with age, too.

Eotaxin is associated with allergic responses and asthma. This has aroused pharmaceutical companies’ interest in drugs that block eotaxin, at least one of which is in clinical trials now. But eotaxin has never before been singled out as having any role in brain aging or cognition.

“All of this made exploring eotaxin further seem like a good idea,” says Wyss-Coray. So they did. Injecting eotaxin alone into a normal young-adult mouse diminished its formation of new hippocampal nerve cells, just as injections of old-mouse plasma or a hook-up to an older mouse’s bloodstream did. The eotaxin-injected young mice also performed worse on spatial-memory tests.

Whether eotaxin actually crossed the mice’s blood-brain barrier is not certain, Wyss-Coray says — although it looks that way. Injecting substances known to incapacitate eotaxin into one hemisphere of a mouse’s brain, while injecting eotaxin into its bloodstream at roughly the same time, protected that hemisphere’s capacity to form new nerve cells.

In any case, crossing the barrier may not be strictly necessary, as stem cells in the brain are always found in proximity to the blood vessels that permeate the brain. Endothelial cells, critical components of blood-vessel walls, have receptors for eotaxin on them. Like Pyramus and Thisbe — those mythological love-struck teenagers who, forbidden to see one another, communicated through a hole in the wall separating their parents’ homes — eotaxin passing through the peripheral blood system may trip receptors on endothelial cells, triggering some further reaction on the brainy side of the divide.

Other blood-borne factors besides eotaxin undoubtedly contribute to age-related declines in brain function. One of the six substances the Wyss-Coray group fingered as likely culprits was a signaling protein called MCP-1, which like eotaxin is a pro-inflammatory molecule, stoking the immune system’s inflammatory fires by attracting immune cells called macrophages. MCP-1 was previously linked to the reduction of the brain’s ability to produce new nerve cells by another lab at the medical school, led by associate professor of neurosurgery Theo Palmer, PhD.

Palmer showed this in a dish, not in the living brain, so the blood-brain barrier wasn’t tested here. He also made no attempt to tie his findings to age. However, the Wyss-Coray lab’s observation that MCP-1 levels increase with age in mice and humans — and the well-established observation that the older we get, the more our systemic inflammatory apparatus tends to get stuck in overdrive — suggests a striking conclusion: Chronic, age-related elevation in pro-inflammatory molecules in our blood may translate into a decline in our brain’s ability to produce new nerve cells and, therefore, to restore worn-out circuitry or incorporate new experiences.

Work by Palmer and others indicates that the inflammatory reaction to an infectious disease a woman might suffer during pregnancy could have a downside for the baby’s brain. And there is some evidence from epidemiological studies that anti-inflammatory drugs like aspirin or ibuprofen may reduce the risk of Alzheimer’s disease.

“I think it’s probably a safe speculation to say that inflammation-producing injuries or disorders may reduce new nerve-cell formation or even accelerate aging,” Palmer says.

The good news is that we may already have ways of countering that tendency. “There are some, no pun intended, no-brainers,” says Palmer.

“Give laboratory mice a running wheel, and they’ll run from 3 to 7 miles every night,” he says. That, in turn, seems to let their brains retain their ability to generate new nerve cells — which makes sense when you consider that steady exercise is known to reduce blood levels of various pro-inflammatory molecules whose concentrations typically rise as we age. Staying healthy and continuing to get exercise as you age is the way to go.

Wyss-Coray wonders, “Can we treat neurodegenerative disorders by administering therapies directly to the bloodstream?” Examples would be drugs that inhibit the action of “bad for the brain” substances in blood, or other drugs that mimic or enhance the action of blood-borne “good for the brain” substances.

By now it has perhaps occurred to you that the next thing you ought to do is dance on down to the local blood bank and ask if they’ve got any young blood for you. No dice. Blood products, like pharmaceutical drugs, are regulated by the Food and Drug Administration, which demands evidence of efficacy — something they won’t have anytime soon. So even if you were willing to jump from a mouse study to the conclusion that you should go for an infusion, you can’t get one.

Meanwhile, Wyss-Coray and his team are examining what happens to the brain’s regenerative capacity when they block eotaxin. They’re exploring any possible connection between levels of eotaxin and other pro-inflammatory immune-signaling molecules to Alzheimer’s. And they’re expanding their blood-borne substance screen from the original 66 chemicals to more than 500 of them, hoping to reel in factors with rejuvenating potential. Having come so close to the Fountain of Youth, why stop? You could say it’s gotten into their blood.

“We’re all Transylvanians now,” says Villeda.

E-mail Bruce Goldman