SPRING 2010 CONTENTS

Home

Little patients, big medicine

Getting serious about helping without hurting

Girls’ day out

Teens with cancer paint the town pink

Hand-me-down blues

Ending depression’s legacy

Paging mom and dad

The future of children’s hospitals

Mother Courage

Mia Farrow’s calling

The inner child

Art offers an opening

A most mysterious organ

Looking for answers about the fetus’s lifeline

DOWNLOAD PRINTABLE

ISSUE (PDF)

Special Report

A most mysterious organ

Looking for answers about the fetus’s lifeline

By Krista Conger

Photographs by Leslie Williamson

It’s the black sheep of human organs — the one we can’t wait to get rid of. Most often, it’s tossed in a bucket for easy disposal. But Lucile Packard Children’s Hospital neonatologist Anna Penn, MD, PhD, and Stanford neuroscientist Theo Palmer, PhD, and their colleagues are keen to get their hands on as many as possible.

“What we don’t know about the placenta is astonishing,” says Penn. “At the end of a pregnancy, there it is. But what does it do in the meantime?”

The placenta used to be thought of as just a glorified housekeeper — delivering nutrients and oxygen, removing fetal waste and generally chaperoning biochemical interactions between mother and child. Because it’s conveniently delivered into the waiting hands of the attending physicians or midwives soon after birth, we know a lot about what it looks like after its job is done. However, it’s been tough to catch it in the act of supporting a growing fetus.

“We’ve really described the structure of the placenta in extraordinary detail,” says Penn. “But its molecular biology is exceptionally poorly studied.”

That needs to change. Recent research suggests that hormones produced by the placenta orchestrate how the fetal brain is organized. Missteps in production or delivery of these molecules during pregnancy can have effects that spin out over years or decades, either in subtle learning difficulties like attention deficit hyperactivity disorder or in more dramatic problems like autism and schizophrenia.

Despite our increasing recognition of the placenta’s critical role in the long-term health of the baby, only a few institutions in the world have dedicated multidisciplinary placental research teams. The placenta doesn’t attract the funding many other organs do, in part because of its transience — it doesn’t develop chronic diseases. Few researchers or physicians spend much time thinking about the placenta. Neuroscientists-turned-placentophiles like Penn and Palmer are swimming against the tide, hoping to substantially increase what’s known about the placenta’s contribution to the later health and behavior of the child.

“The placenta has always been credited with supporting the baby,” says Palmer, “but the link between placental anomalies and later cognitive deficiencies is really strong. Much stronger than we had anticipated.”

Premature babies, deprived of this molecular hormone factory too early, bear the brunt of our ignorance. Recent research has shown that important portions of their brains remain abnormally small for years. Neonatologists like Penn can sustain them with breast milk, and perform basic life support techniques, such as helping their lungs to breathe or their hearts to function better, without knowing what they’re not getting from the now-discarded placenta. And yet the key to helping these children live successful, normal lives may very well be recreating as closely as possible the conditions they left behind in the womb.

“It used to be that the big focus was on keeping these kids alive,” says Penn, who recently received a $1.5 million New Innovator Grant from the National Institutes of Health to investigate how placental hormones affect fetal brain development. “It’s not that that’s no longer a problem, but now we’re better-equipped. We can start to think about their long-term status. But we don’t know what they are missing physiologically, and how we can give that back.” At least not yet.

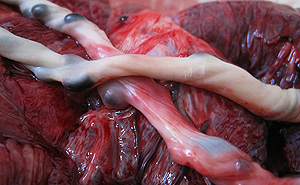

In this close-up, the umbilical cord lies looped over the placenta. The cord carries enriched blood to the fetus.

In this close-up, the umbilical cord lies looped over the placenta. The cord carries enriched blood to the fetus.

As part of her research, Penn’s working to establish a “bank” of full-term, premature and damaged placental samples to use for future studies. The unique bank, which the researchers hope to eventually share with physicians and researchers nationwide, will contain a wide variety of samples, from tissue to genetic material, and will link to information about the long-term health of the mother and baby. Unfortunately, federal funding for tissue collection can be hard to come by. Also, because placentas quite literally straddle the nebulous boundary between obstetrics and pediatrics, many different doctors are needed to coordinate such an effort. But the researchers have forged ahead, and will begin gathering placental samples this spring. Their expectations are high.

“Lucile Packard Children’s Hospital has over 5,000 births per year,” says Penn. “If we can capture placentas from even half of these, we’d have enough tissue for even large-scale studies.” She, Palmer and their colleagues — placental pathologist Amy McKenney, MD, geneticist Julie Baker, PhD, and developmental biologist Gill Bejerano, PhD — envision linking the structure and gene and protein levels in the placenta samples with the mother’s medical history and the developmental outcome of the babies months and years later. Their tongue-in-check name for the effort?

The Bucket Brigade.

Dressed in a black top and pants and wearing a colorful, chunky necklace, Penn is happy to discuss her work. Her tiny, tidy office is brightened by pictures of her two children on one wall and a beautifully serene Asian floral scroll given to her by the parents of a patient — a boy born four months too early. Although she spends about 75 percent of her time in the lab, she treasures the days she spends caring for infants in Packard Children’s intensive care unit for newborns and its nursery, keeping kids alive hour after painstaking hour.

Liam Sikes was one of those kids. Born more than three months early at Dominican Hospital in Santa Cruz, Calif., in December 2005, Liam was quickly transferred to Packard Children’s for advanced care. Penn threw her medical arsenal at the 1-pound, 9-ounce baby as he struggled with kidney failure, severe infection and later a common but severe eye condition known as retinopathy of prematurity. Many times she wondered if he would survive. But the tiny baby beat the odds.

“When he was discharged, we were completely blessed and amazed,” Liam’s mother, Paris Trudeau-Sikes remembers. “We were coming home with our son thinking, ‘Thank you. This is all we asked for.’” But then the waiting began — because they knew Liam might still have a huge struggle ahead.

“Premature male babies are more at risk than equally premature girls for just about everything, including death, lung and vision problems and long-term neurodevelopmental delays,” says Penn. “But we don’t really know why.” This isn’t to say that premature girls face no risk, merely that for boys it’s higher. Specifically, girls have about a one-week advantage over boys. That is, a girl born at 24 weeks and a boy born at 25 weeks will fare about the same statistically. She believes that some of this gender difference lies in the sudden loss of protective sex hormones provided by the placenta — hormones that baby girls can make for themselves, at least a little, and boys cannot.

“We spent the first couple of years wondering about Liam’s neurological outcome,” says his mother. “And now, even though his MRI before discharge looked normal, it’s apparent that he does have a neurological injury.” Now 4 years old, Liam has cognitive difficulties, and problems with his vision and motor skills.

If Liam had been a girl — or if physicians understood how to give back the placental hormones he would have had in utero — he might not have these challenges. “In an ideal world,” says Penn, “we’d take blood or spinal fluid from these babies, assess the levels of the hormones that we know are important for brain development, and give back as medications those that are missing.”

But first we have to figure out what they are.

For such an important organ, the placenta is pretty ugly. At full term it is an approximately 1-pound, flattish and roundish mass resembling a deflated soccer ball or an unleavened loaf of bread. (In fact, the word “placenta” originates from the Latin word for cake.) It has a maternal side that faces the uterine lining and a fetal side facing the inside of the uterus. And, of course, it’s very, very bloody.

That’s because it’s chockfull of arteries and vessels to deliver oxygen and nutrients from mother to child. The two blood supplies don’t mix freely, however. A thin layer of cells called the placental barrier separates the network of vessels on the maternal side of the organ from those on the fetal side. Some molecules such as oxygen, carbon dioxide and certain medications and hormones either diffuse or are actively transported across the intervening tissue. Other circulating factors, like most cells, are blocked to protect the fetus from harm and attack by the mother’s immune system.

Penn became interested in the placenta gradually. As a graduate student in the laboratory of Stanford neurobiologist Carla Shatz, PhD, she studied early spontaneous activity and organization in the developing neural system. When she joined the laboratory of Stanford developmental pathologist Matthew Scott, PhD, as a postdoctoral scholar, she investigated factors that control cerebral activity. She describes herself as a developmental neurobiologist.

“This is the next step,” she says of her current line of research. “I wanted to explore what the extrinsic organizing signals are, and what happens when they are suddenly lost. What stops, and what keeps going? Are there big things that are missing when we take away the placenta?”

Penn quickly learned that the placenta is more than just a molecular transit station orchestrating the trafficking of maternal and fetal factors. It also makes its own hormones to support the developing pregnancy. Some we know about, including the sex hormones progesterone and estrogen, which thicken the uterine lining and support the first steps of egg development in female fetuses. Progesterone and estrogen are also involved in brain development, and may be responsible for the varying survival statistics between premature boys and girls. But many more placental factors remain mysterious.

“We have a little list of candidates,” says Penn with a grin. “About 100.” She studied microarray data generated by Baker, another placenta enthusiast, to identify hormone-related genes expressed in the mouse placenta at various times during gestation. To earn a spot on the list, the hormones had to be shared between mice — the study animal used by the researchers — and humans; to be secreted from the placenta; and to — theoretically at least, based on their DNA sequence — cross the blood/brain barrier in the fetus to influence the development of the growing brain.

“We’re also interested in the many small peptides that appear to be secreted from the placenta,” says Penn. “They increase during the course of the pregnancy and there is some evidence that they get to the fetus. But nobody knows what they are doing.”

Obviously, one problem with studying the placenta is its relative inaccessibility during gestation. It’s been difficult to come up with a way to block or amp up the expression of genes in the placenta in mice without also changing their levels in the mother or fetus. But Penn and her colleagues have done it.

She and postdoctoral scholar Danielle Leuenberger, PhD, took advantage of the fact that the placenta develops from the outer cells of the blastocyst — the ball of cells that develops from a fertilized egg. (Cells inside the ball become the fetus.) They used a virus to infect only these outer cells with the DNA of candidate genes coupled to on and off switches called promoters that allow them to be expressed or shushed at specific points during gestation. They also used DNA that reduces the natural expression of these genes. They then implanted the developing embryos into female mice. They hope that by toggling the individual gene candidates on and off, they will be able to identify those molecules that play a vital role in brain development.

In addition to identifying new placental hormones, Penn is working to figure out why boys are more at risk than girls for neurodevelopmental problems. She’s found that exposing newborn male mice to periods of low oxygen generates changes in their brains that mimic the effects of prematurity in humans. The brains of female mice also change, but the response is less pronounced. They plan to test whether giving the male pups sex hormones usually provided by the placenta can prevent or reverse the damage.

As with all research, it will take time before it can be applied. In the meantime, there is still hope for the future of these children. "We are so excited at the consistent progress Liam is making," says his mother, Trudeau-Sikes. "With the dedicated help from Liam's therapists, teachers, and doctors he continues to make great strides. And, my hope for Anna's research is that, in the future, it will be possible to develop medicines that will help the outcome for preemies at birth and through their early development."

Penn is hopeful, but realistic. “We finally have the money to start to look at human placenta and to develop the mouse models that may eventually lead to help for premature babies,” she says. “There are almost too many different interesting questions to explore.”

E-mail Krista Conger