SUMMER 2009 CONTENTS

Home

In the crosshairs

Basic science under the microscope

Harkin’s hope

Re-creating America as a wellness society

Anatomy of an experiment

Chasing down the cell’s gatekeepers

The Catalysts

How the farm became a giant force in biology

Crossovers

Learning to speak “doctor”

The science pages

Scientists built the web. Do they love web 2.0?

Opening doors

Finding funding for graduate students in basic science

Superheroes

Turning Sadness Upside Down

By Erin Digitale

Illustration by Mark Matcho

Portrait Photography by Trujillo-Paumier

“Is he normally like this?” The emergency room team stared at the limp boy, slumped helplessly in his father’s arms. Five-year-old Dylan Jewett could scarcely hold his eyes open.

He’s never like this, said Danah and John Jewett, describing their struggle to rouse their son. Dylan was usually full of energy, but on the morning of Nov. 14, 2008, he didn’t want to wake up. He’d respond briefly, then nod off. He was sliding around on the edge of unconsciousness.

Hearing John and Danah’s answer, the ER staff at the naval hospital in Guam sprang into action. They hooked Dylan to an IV, drew blood and hurried the boy to a CT scan. The worried parents wondered what could be wrong with their spirited son, who loved superheroes, Sunday school and building giant, complex tracks for his Thomas the Tank Engine toy.

The diagnosis came quickly. The CT scan showed fluid buildup pressing on Dylan’s brain. Dylan needed to be airlifted to the Philippines for emergency surgery that would place a shunt to drain the fluid. The scan also showed a mass on the brain stem, which would be removed in a second surgery, a doctor explained.

The hospital staff helped Danah prepare for the 1,600-mile Medevac flight to Manila. John stayed on Guam’s Andersen Air Force Base to look after the family’s 11-month-old, Jayden, and organize a transfer from his posting with the Air Force’s 644th Combat Communications Squadron to a position back in the United States.

Dylan would be OK, his parents told themselves. The doctors said he would recover.

At the Stanford University School of Medicine, a young physician-scientist who treats children with neurological problems like Dylan’s thinks back to what set the course of her career.

“One patient just broke my heart,” says Michelle Monje, MD, PhD. Monje, a neuro-oncology fellow at Lucile Packard Children’s Hospital, cares for children with brain cancer and conducts research on a rare, vicious brain tumor that arises in school-aged children and usually kills them within a year of diagnosis. The emotional impact of this cancer, diffuse pontine glioma, hit her hard when, as a medical student, she became close to the family of a girl dying of the disease.

“She was beautiful and vibrant — everything a 9-year-old girl should be,” Monje says. Caring for the patient and observing her decline and death, Monje grew increasingly frustrated that medical science could do nothing to reverse the catastrophic illness. Worse, the disease’s five-year survival rate of 1 percent had not improved in 35 years. Monje decided she wanted to change that.

But she knew it wouldn’t be easy. For decades, scientists studying diffuse pontine glioma had been working in the dark. The tumor appears in the brain stem, the nerve conduit at the base of the brain that funnels information from the spinal cord to the gray matter and regulates basic body rhythms. Scientists hadn’t been able to get direct access to the cancer cells because a biopsy of the brain stem can irreparably damage the body’s control of breathing, heartbeat and consciousness.

Although, like any scientist beginning a long and challenging research project, she anticipated an uphill slog, Monje is feeling cautiously optimistic of late. This year a bereaved family donated tumor tissue from their deceased child for her team to study. Now they have a window into the tumor’s workings, giving them a sort of scientific version of new superhero powers.

“We probably have the only growing brain stem glioma cells available, period,” Monje says. She and her colleagues have managed to culture cells from the autopsied brain tumor. They believe this is the first such culture anywhere in the world.

“It’s incredibly valuable tissue,” she says. “For the first time, we’re going to be able to ask important practical questions about the biology of this tumor.”

The Jewett family had been on Guam only a month before their dash to the emergency room.

John and Danah had longed to go overseas since their wedding nine years earlier. When they found out the Air Force was transferring John from Georgia’s Robins Air Force Base to Guam, they were thrilled.

“We were like, ‘woo-hoo!’” Danah says. “Dylan was a little bit bummed to be leaving his friends in Georgia, but he was really excited about making new friends in Guam.” John, who had been in the Air Force nearly a decade, was being transferred to a combat communications unit responsible for establishing reliable communications in the early stages of military operations. The new job involved “more kicking of equipment,” John says in a half-official, half-joking tone.

When the family moved into a duplex on the base in Guam, Dylan quickly settled in, riding bikes with the neighbor kids and playing in the backyard faucet in the tropical heat. John took him exploring — to check out a cave and collect coconuts in the jungle — so that Danah, who was pregnant and nauseated, could get some rest. Before the first trip to church, Dylan drew a stack of pictures so he could bring one as a gift for each child in his new Sunday school class.

John and Danah weren’t surprised Dylan was eager to make new friends. He was the sort of little boy who loved other kids and wanted to be sure the people around him were OK. Back in Georgia, after Danah introduced him to old Superman reruns, one of his favorite games had been dressing up in his superhero outfits.

“He would put his regular clothes over his Superman costume, so that if the need arose when we were out somewhere, he could be Superman,” Danah recalls, laughing.

Dylan’s cheerful empathy and large imagination put him at the center of a contented idyll of little-boy life.

Yet during their first few weeks in Guam, John and Danah noticed some minor physical problems. Dylan was more tired than usual, stumbled into a few walls and suddenly became afraid to walk up stairs. Maybe he needed corrective shoes, they thought, or perhaps he was coming down with a germ. Danah scheduled a routine doctor’s checkup, but before the appointment, the family ended up in the emergency room.

Diffuse pontine glioma comes as a shock to families, explains Monje, one of Dylan’s doctors. She’s a newly minted physician-scientist, 32 years old, with a direct, sincere manner.

Patients usually come to the doctor with about a month’s history of double vision, a weak arm or leg, or difficulty balancing, Monje says, symptoms most parents assume will have a straightforward solution. The medical team does an MRI, which shows a distinctive swelling in the ventral pons, a region at the front of the brain stem.

“Families get a horrible diagnosis,” she says. The tumor can’t be cut out because the cancer cells entwine themselves with healthy tissue, like a sweater knitted of multicolored yarn, with no border between malignant and normal. Chemotherapy doesn’t work. Radiation is only a temporary fix.

“Most families opt to do a six-week course of radiotherapy, which stabilizes the disease for a period,” Monje says. “But it usually comes back within a year, at which point it’s rapidly progressive and always fatal. It’s a hard disease.”

Monje stops talking, looking pained. She’s been bouncing her 8-month-old son on her lap, savoring the brief evening interval between her clinic visits and the baby’s bedtime. He teethes happily on a frozen bagel, then reaches to smack his mother’s laptop, which shows an MRI scan image displaying unmistakable signs of diffuse pontine glioma. The scan depicts Dylan Jewett’s brain.

Monje’s mentor, pediatric neuro-oncologist Paul Fisher, MD, has given the diagnosis of diffuse pontine glioma to about 100 families in his 15 years at Packard Children’s. “I go out of my way to make clear to parents that it’s not their fault,” Fisher says. “I tell them there was no window of opportunity when the tumor could have been removed. The prognosis is not because of when they brought their child in or because of anything they did or didn’t do.”

Danah Jewett didn’t get such a sensitive delivery of dylan’s cancer diagnosis. It was Nov. 16, about 24 hours after the emergency surgery in Manila. The shunt placement had gone well, the fluid drained off Dylan’s brain, and the boy woke alert and full of questions. What happened to me? What’s that squeezy thing they’re putting around my arm? Will I be able to walk again, Mommy?

Your body made an accident in your brain, Danah told him, using words she hoped would suit her curious boy’s understanding level. The doctors will do another surgery, and you’ll get better.

Michelle Monje, MD, PhD, a neurologist who cares for children with brain cancer, is researching an especially deadly childhood tumor.

Then the results from Dylan’s MRI came back.

With no warning of the grim news he had in store, a doctor handed Danah some pieces of paper — information about diffuse pontine glioma printed from the Internet. This is what your child has, he said bluntly.

Danah gripped the printout. It was just two sheets of paper, delivered without a hint of compassion. Feeling marooned, she read the prognosis.

“I said, ‘Is this right? Is this correct, that he has eight to 12 months to live?’” she says, her voice rising with agitation as she recalls her astonished disbelief. “The doctor said, ‘That’s what the literature says.’

“I think I was feeling, ‘God’s going to do a miracle. There’s got to be a plan here somewhere,’” she adds. “I thought, maybe this can’t be right; I have to find out more about this and not just accept these two pieces of paper.”

She phoned John in Guam to give him the news.

“My response isn’t printable,” says John. “I was in shock.”

Turning autopsied tumor cells into useful laboratory tools was so daunting Monje sometimes doubted it would ever happen.

The first hurdle was ethical: When would it be acceptable to ask parents’ permission for a postmortem tissue donation from their terminally ill child?

Monje tackled this dilemma while still a medical student at Stanford, asking Fisher if he would solicit postmortem donations from families whose dying children had received radiation to the hippocampus. She wanted to test whether the radiation impaired neuron growth, a part of her research on minimizing the harm caused by cancer radiotherapy. Both Monje and Fisher felt torn between the desire to advance science and concern for current patients. But to their surprise, the few carefully selected families Fisher approached said yes.

“What we learned,” Fisher says, “was that even in the most desperate situations, the families were amazingly supportive of science and of helping others.”

The diffuse pontine glioma cells, however, arrived under even more unusual circumstances, as an unsolicited gift. A family whose child was in late stages of the disease asked Monje, unprompted, if his tissues could help other children after his death. She told them about her research, and they offered to donate his brain tumor.

“This family was so generous and selfless in the face of unimaginable tragedy,” Monje says. “They kept saying, ‘We just don’t want anyone else’s child to go through this.’ They’re amazing people.”

But Monje’s team still faced a second set of technical hurdles: When the child died, would they be able to coax the cancer cells to live in the lab? The answer depended on speed, technical know-how and luck. If the patient passed away on a weekend — when the pathology lab that performed autopsies was closed — the tumor cells wouldn’t be usable by the time they reached the lab. And no one was quite sure what culture conditions would be best for the cells.

The offer of the donation instigated intense activity as Monje gathered a team to help use the tumor for research. Fortunately for the scientists, the child died on a Thursday evening. Fourteen hours later, Monje’s colleague Siddhartha (Sid) Mitra, PhD, a postdoctoral research fellow in neurosurgery at the Stanford School of Medicine, began coaxing the postmortem tumor cells to grow in a dish.

“We got almost 35 milliliters of tumor — a huge amount,” says Mitra, demonstrating how he immersed the pieces of the tumor sample in a sterile flask of buffer to measure their volume. The total tumor sample was about as big as a golf ball.

The diffuse pontine glioma was so advanced that many tumor cells were already dead. Mitra spent several hours gently dissociating the living cells from the dead debris, a slow and painstaking process. The yield — about 2 million live cells — was divided between three baths of liquid cell food to maximize the chances of hitting on the nutrient combination that kept the cells happy. After a few weeks of nurturing the nascent cultures, Mitra began looking for specific tissue-identity markers on the surface of the growing cells, checking to ensure they displayed the molecular characteristics of cancer.

The cells are now thriving. And, despite their malignant menace, the vista they present under a microscope is oddly beautiful. For instance, in one culture condition Mitra used, each cell sends out thready arms that make it look like a small child’s drawing of the sun.

For Mitra, knowing that the cells under his microscope are the result of a specific child’s illness has changed his feelings about his work. Though he was trained in the ivory-tower paradigm where you peer at a dish of cells and the outside world falls away, he now says he could never go back to purely basic research.

“It’s been a complete eye-opener,” he says. “I never thought I would be doing something that could help someone in my lifetime.”

For the next validation test, Monje injected cultured tumor cells into immunodeficient mice to see if they cause tumors in vivo. Based on early results, Monje and Mitra are optimistic.

After Dylan’s diagnosis, John joined Danah and Dylan in Manila. Baby Jayden stayed in Guam with a family Danah had met in church until John’s parents could fly from Arizona to collect their grandson.

When John arrived, he was glad to see that Dylan was more his old self — bits of his personality were peeking through his illness. “Dylan sent me out from the hospital in the Philippines with the assignment that he wanted me to get Danah a bracelet with stars and rainbows on it,” John says.

But in Manila, John and Danah, 15 weeks pregnant with the family’s third child, received a second piece of tragic news. Danah’s first prenatal ultrasound exam showed the fetus lacked most of its brain. If it survived gestation, the baby would be expected to live only a short time after birth.

Absorbing the threat to one child’s life and the certain loss of another, Danah leaned on her Christian faith to get through each day.

Her faith was a big influence on her decision to carry her pregnancy to term, though she had the option to terminate. “It’s not up to me to take this life,” she says. “I want to hold this baby and love him for whatever time God gives me, whether it’s five minutes or five days.” Danah and John decided to try to enjoy the pregnancy, knowing it would comprise the majority of their time with their third child. When they found out the baby was a boy, they named him Judah.

Danah also relied on her faith to cope with the barrage of discouraging information about Dylan’s disease. Surely, God had a plan for her family somewhere in this complicated tangle of sad news.

John, who has the practical, no-nonsense demeanor of a career Air Force man, coped a bit differently. “I didn’t come to being religious until this whole experience,” he says. In the Philippines, he hung on by focusing on the long, complex list of tasks he needed to complete to get the family transferred to a naval hospital in San Diego so that Dylan could get better medical care, John and Danah could be close to their extended families, and everyone could figure out what to do next.

“Did you ever try getting a document notarized in downtown Manila?” John asks dryly.

Describing the person Dylan was before his illness, John shows a combination of affection and wry humor. Dylan loved to play hide-and-seek, he says, “But his choices for hiding spots … .” He trails off and shakes his head, smiling.

Dylan improved enough that on Nov. 21, the day before the family left the Philippines, his parents could take him shopping to choose a gift for Danah’s mother, with whom he was especially close. That night, on the phone, Dylan blurted out the surprise in spite of himself. “He said, ‘I can’t tell you what it is, Nana. But it’s a necklace,’” Danah recalls with a grin.

For a few days after the Jewetts reached San Diego, Dylan did well. “He could almost walk by himself,” Danah says, describing how she or John would give Dylan steadying hands for trips to the bathroom. And Dylan was delighted when John’s parents brought his little brother to the hospital for a visit.

“Give me that baby,” he said happily, his speech already slurred by the tumor. “Gimme a hug, baby brother.”

So far, the diffuse pontine glioma cells sid mitra is tending are thriving in their culture dishes. That’s got the scientific team bubbling with excitement about what’s next for the cells.

To start, Monje is writing a grant proposal to put the cells through a compound library screen, a test that will check whether any of the 130,000 chemicals in Stanford’s library of putative drugs — compounds synthesized over years of research in dozens of labs around the world — will inhibit the cancer’s growth.

At the same time, Mitra and a colleague, neurosurgery resident Gordon Li, MD, are testing the tumor for a specific surface marker, epidermal growth factor receptor variant III (EGFRvIII), a protein that appears on many types of solid tumors, but never on healthy cells. Mitra’s early results suggest diffuse pontine glioma may display EGFRvIII on its surface.

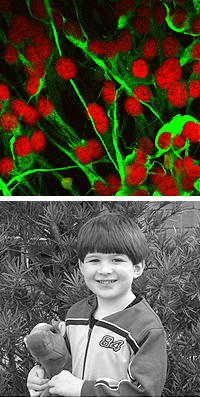

Dylan Jewett (bottom) and his family confronted diffuse pontine glioma — a little-understood childhood cancer. Top: Cells from the only existing growing laboratory specimen of this type of tumor.

“This is fantastic news because it means something unique to cancer is sticking out from the cells,” Mitra explains. The unique cancer marker may help the scientists design drugs or other therapies that target the cancerous cells while leaving healthy brain cells alone.

Better yet, Albert Wong, MD, the professor of neurosurgery who leads the lab where Mitra and Li work, has already spearheaded a multiyear effort to develop a vaccine against EGFRvIII. The vaccine, designed to tag cancer cells for immune-system destruction, has made it successfully through phase-2 clinical trials against glioblastoma multiforme, a brain tumor found in adults.

Li is eager to try the vaccine in children with diffuse pontine glioma. Ironically, the tumor’s utterly dismal prognosis will likely speed this research: Because life expectancy after diagnosis is so short, he’ll need only a year or two to figure out whether the vaccine significantly prolongs life. And because the vaccine has already advanced through early safety and efficacy tests for use in adults, the treatment could be given to children much more quickly than any therapy the team might develop from scratch.

For the longer term, Monje plans a series of experiments to dovetail with earlier studies she has been running in the lab of Philip Beachy, PhD, professor of developmental biology, on healthy brain stem development. Starting from the clue that diffuse pontine glioma appears at a specific juncture in childhood, with diagnosis around age 7, she has studied healthy brain stem development in mice at the equivalent age. She’s asking what could make a well-defined group of normal brain-stem cells veer toward malignancy at that exact stage of growth. Now, for the first time, she’ll be able to check whether her hunches about the cancer’s origins play out in real life.

“This donation opens up the world in terms of being able to study this tumor, to understand the biology behind its growth and to develop therapies,” Monje says. “It’s incredibly valuable tissue.”

On Dec. 12, Dylan was flown from San Diego to Packard Children’s, a transfer suggested by a doctor in San Diego who had trained under one of Packard’s pediatric neurosurgeons.

The Packard neuro-oncology team would have the expertise to give radiation therapy that might quiet the tumor for a while, the San Diego doctor said. The transfer made sense to the Jewetts: “The naval hospital was not really geared toward children,” John says, and Packard was near Travis Air Force Base, where he had secured a new posting. Besides, Dylan’s beloved Nana lived just a few hours’ drive from Packard and would be able to visit often.

“We were all geared up, wanting that radiation,” Danah says.

Danah and John Jewett Dylan’s parents at home in the San Francisco Bay Area a few months after Dylan’s stay at Packard Children’s Hospital.

The signs for Dylan were not looking good. Starting in San Diego, he declined rapidly, growing weaker and sleepier and struggling to speak or swallow. Nothing was wrong with his surgical shunt; nevertheless, a new CT scan showed fluid again accumulating on his brain.

At Packard, Monje and pediatric hematologist-oncologist Carolyn Russo, MD, assumed responsibility for Dylan’s care.

“He was really in extremis,” Monje says, describing her first impression of the boy. “This was the biggest brain stem glioma we’d ever seen.”

“I very vividly remember John telling me that the most important thing was quality of life for Dylan,” Russo adds. “John and Danah were already playing that difficult balance of risk versus benefit. And from a medical standpoint, these tumors are all terrible, but Dylan had the worst of the worst. It was a very aggressive pontine glioma.”

Seeing Dylan’s condition, Russo was filled with trepidation about what lay ahead for the family.

“The most disgusting thing about this tumor is that not only does your child die, but he dies not as the same child you knew,” she says. “These children become paralyzed, lose all functions of the head and neck, can’t swallow, can’t talk, develop eye movement problems, and then they lose consciousness. They aren’t able to be children.”

John and Danah decided to begin a six-week course of radiation therapy for Dylan, but re-evaluated their decision after just three treatments. His disease was so advanced that radiation couldn’t provide any substantial improvement in his condition, the doctors told them. Meanwhile, the radiotherapy itself required anesthesia, which meant Dylan — already ravenous from other medications he was receiving — couldn’t eat for several hours each day. The balance of negligible benefit against severe discomfort made the radiation seem like torture.

But Danah and John were nevertheless hoping something positive could come from their growing tragedy. In the midst of their first day at Packard, Danah asked Monje whether they could donate Dylan’s tissues after his death, thus providing the medical research world its only growing brain stem glioma.

Monje was stunned.

“That’s a pretty amazing place to be in so early in the process,” Monje says softly. “I can’t imagine it, as a mother.”

But for John and Danah, deciding to donate Dylan’s tumor was the straightforward part of dealing with their grief. Right now, the diagnosis of diffuse pontine glioma is “a death sentence for kids,” John says. “No parent should have to hear that, but doctors can’t study the disease unless somebody makes a donation.”

“We couldn’t think not to,” Danah adds. “Our options were to try and help, or to let him die in vain. Now we feel like his story lives on, even though he’s not here physically. I see such a big purpose behind it, way bigger than I could understand or comprehend.”

After the radiation treatments stopped, Monje and Russo did the best they could to make Dylan and his family comfortable.

“As physicians, when we can’t offer curative therapy, there’s a temptation to throw up our hands and say there’s nothing we can do,” Russo says. “But there are always things we can do, even when we can’t make the tumor go away.” The doctors helped arrange for Dylan to move to the George Mark House, a pediatric palliative-care facility in Palo Alto, so his family could receive care in a homelike place during his last days.

Monje, thinking about what would make Dylan happiest, also suggested a change to his care. Dylan was always hungry from his steroid drugs and asked continually for chocolate milk. The doctors had limited his milk intake because it could make his sodium levels drop.

“Toward the end, we decided the most important intervention was as much chocolate milk as he wanted,” Monje says. “After all, he was a 5-year-old boy.”

“Dr. Monje was awesome,” Danah says, remembering the decision. “She said, ‘We have got to figure out what is more important for this kid; he’s terminally ill either way.’ She said if it was up to her she’d hook him to a chocolate IV. He couldn’t play with toys any more, and he couldn’t move his hands very well, so the chocolate milk was the one thing that helped him to be happy.”

Dylan died the evening of Jan. 8, 2009. Near the end of his life, Danah reassured her son that “it was OK to go be with Jesus, there would be less hurting, and we would be OK.”

He passed peacefully and without pain.

Early on Jan. 9, Mitra took a seat at the lab’s sterile workbench and began culturing Dylan’s tumor.

The sobering thought that the cells he carefully plucked from the surrounding tissue would be the only cultured specimens of their kind lent extra meaning to the six hours of work. The cells responded well to his ministrations. They’ve gone on to open the dramatic vista of scientific possibilities for which Monje and the other researchers are so grateful.

Today, Monje has complicated feelings about working with Dylan’s tumor cells. As a scientist, the exhilirating prospect of using them to find effective new treatments for diffuse pontine glioma fills her with excitement and hope. As a mom, and as someone who cared for Dylan and his family, she struggles.

“Dylan is definitely a patient I think about a lot,” she says. “When you’re in the lab, you’re very analytical and very clinical. But there is an emotional content to this tissue that is very present for me all the time.” She recalls with sadness a comment that John made when she reviewed Dylan’s autopsy findings with the Jewetts. He said, “It’s so strange that the tumor gets to live on but Dylan doesn’t.”

In the months after Dylan’s death, as his family gradually began learning how to carry on without their oldest son, Danah used the online journal she keeps for family and friends to describe her feelings about Monje’s research:

... In everything God has a plan. I so wish this one did not involve Dylan, but it does. That being what it is — Dylan’s tumor specimen is the only living tumor of this type currently in the world. That means his is the only one they have to study right now. ...

... Wouldn’t it be wonderful to know that because of Dylan’s loss of life, other children could be helped and live? That parents may possibly not have to hear, “There is nothing we can do for your child,” but “Here is something that could help.” That news excites me and makes me happy. I just wish it was not Dylan. I do think of Dylan and how much he loved children. He would be so excited to know that he could be helping other kids.

Epilogue

Judah Jewett was born by caesarean section at 8:23 a.m. April 24, 2009. He was 5 pounds, 10 ounces and 16¾ inches long. He lived 26 hours, held and cuddled most of that time by his parents, his Nana, and many other family members and close friends who came to visit the hospital. After his death, John and Danah donated his heart valves so they could be used to help another infant. Danah also decided to pump breast milk to donate to a local milk bank.

In her journal, Danah described agonizing before Judah’s birth over whether to hope that her little son could be miraculously healed. At last she wrote:

I love Judah for who he is. … The Bible says children are a blessing and that means they are a blessing. It does not say children are a blessing if they get to grow up into adulthood. ... No matter how long or short their lives are, they are a blessing.

Danah’s Journal

During and after Dylan’s illness, Danah kept an online journal to update family and friends on what was happening in her family’s life. Here, she tells about sharing her favorite memory of her son during his memorial service: [At around age 3,] Dylan would often tell “Bible stories.” The stories were really cute and usually went something like this, “Jesus walked on water on the boat and the bad guy came and there was the good guys and then Spiderman came and was like boush bam bang….”

More of Danah’s online journal