SUMMER 2009 CONTENTS

Home

In the crosshairs

Basic science under the microscope

Harkin’s hope

Re-creating America as a wellness society

Anatomy of an experiment

Chasing down the cell’s gatekeepers

The Catalysts

How the farm became a giant force in biology

Crossovers

Learning to speak “doctor”

The science pages

Scientists built the web. Do they love web 2.0?

Opening doors

Finding funding for graduate students in basic science

Harkin’s hope

Re-creating America as a wellness society

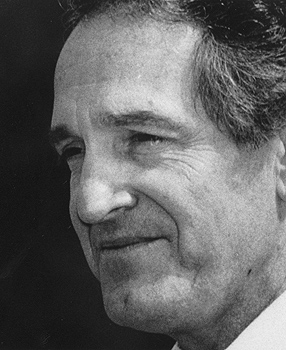

Photo courtesy of the office of Sen. Tom Harkin

Few people in Congress are as influential as Iowa’s Tom Harkin when it comes to shaping America’s health.

As chair of the Senate appropriations subcommittee that funds the National Institutes of Health, he’s in the enviable position of deciding how billions of biomedical research dollars are allocated. For instance, in February Harkin and a Senate colleague, Arlen Specter, secured $10 billion in the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act for studies concerning health and medicine.

For many years, Harkin’s been a lone voice in an effort to include prevention as a key component of any overhaul of the national health-care system. He believes a “wellness society” focused on disease prevention, healthier lifestyles and good nutrition is critical to reducing costs and saving lives. In fact, as far as prevention goes he takes it personally, launching a variety of wellness incentive programs in his own office. For instance, staffers gain “wellness days” for meeting challenges such as eating five fruits and vegetables a day or participating in at least a minimum amount of physical activity per week.

The Iowa Democrat, a 34-year veteran of Congress, has long believed that America has “a sick care system, not a health-care system.” Now, as Congress and the White House tussle with the hard realities of reforming the health-care juggernaut, Stanford Medicine’s executive editor Paul Costello asked the senator to talk about basic science, prevention and his own prescription for staying healthy.

With the growing national debt, some would argue that biomedical research that simply expands human knowledge is a luxury, and government-sponsored research should focus solely on health-care applications. What do you think?

Harkin: Basic research is not a luxury. Without the research of the past 20 or 30 years, we wouldn’t have many of the treatments and cures that we benefit from today. But unless basic research is funded by the federal government, it won’t get done. So it would be extremely shortsighted to abandon our efforts in this area. At the same time, I often note that we named the NIH the National Institutes of Health, not the National Institutes of Basic Research. We must always remember that the ultimate goal of government-funded biomedical research is better health, not just more basic research.

When you talk to your Senate colleagues about why an investment in NIH redounds to the benefit of the U.S. economy, do they get it?

Harkin: Yes, and different reasons resonate with different members of Congress. Some support the NIH primarily because they believe in the potential of science. Others have a personal story, such as a loved one battling cancer. For some, the economic impact is the draw — they see the money coming to universities in their states and they realize that the NIH can be a powerful economic driver.

As you travel around your state, what are your constituents telling you about the need for a robust NIH or for biomedical research more generally?

Harkin: I meet with constituents all the time who are affected by different diseases — either their own diagnosis or that of a loved one — and they understand that NIH support is the key for the people they love. This is particularly true for diseases that are less common, the so-called rare and neglected diseases. For them, the NIH is their only hope.

These days, much of your attention is on reforming health care. What are the essential elements you feel must be included in a reform proposal?

Harkin: Preventive care needs to be integrated so that this nation is a healthier nation and we begin to bend the cost curve on health-care expenditures.

This means private health insurance and the Medicare and Medicaid programs must reimburse for effective preventive services, such as annual physicals, mammograms, screenings for diabetes and depression, tobacco cessation programs and nutrition counseling — to name a few. This also means removing barriers to preventive services, including getting rid of co-pays and deductibles.

Currently, many insurers will reimburse for nutritional counseling after someone is diagnosed with diabetes but not when they are pre-diabetic or at high risk of developing diabetes. This is ridiculous!

And we need to use tax incentives to encourage employers to offer wellness programs in the workplace — things like smoking cessation, depression screenings and fitness programs.

Who’s going to steer these changes?

Harkin: We’d create a federal prevention and public health council to improve coordination among federal agencies in incorporating wellness into national policy and to develop a national strategy with public health goals and objectives for the nation to achieve. This means that the Department of Transportation will talk to Health and Human Services before handing out transportation funding, and make sure roads are built with sidewalks to encourage walking and bike riding to jobs and schools. And this means the USDA will talk to the Department of Education and make sure our kids get healthier foods in schools. Those types of interactions must become a standard part of our government.

We’d also want an investment fund to provide for an expanded and sustained national investment in prevention and public health programs to improve health and help restrain the rate of growth in private and public sector health-care costs. The investment fund will be used each year for prevention efforts in our communities — bike paths, immunization programs, mental health screenings, nutrition counseling and on and on. This will let communities address the unique health challenges in their area.

What role do medical schools play in this?

Harkin: Medical school and residency curricula should include training in prevention and public health. It’s hard to believe, but currently our health professionals get little formal training in this area.

What’s your own personal wellness program?

Harkin: I incorporate wellness into my daily routine. In addition to eating as many fresh fruits and vegetables as possible, I take a walk each morning and take the steps to my office, rather than the elevator. And I wear a pedometer to track my progress. This spring, I’m also participating in the Humana Foundation’s American Horsepower Challenge, where I’m competing with middle school students in Iowa, recording our steps each day and viewing online how far we’ve come. We’re all tracking our progress online. I also enjoy hiking and being outside as much as I can.