SPRING 2009 CONTENTS

Home

The demonization of immunization

Shots get the once-over

What is a vaccine?

Immunization demystified

Asking How

Vaccine Side Effects Probed

When science gets hijacked

NBC News chief medical editor tells why she broke her silence

Insourced to India

A vaccine for a scourge of the developing world

Peet’s passion

The medical education of Amanda Peet

Field yields

Can genetically engineered plants provide vaccines?

Shoot it, don’t smoke it

An injectable tobacco-grown vaccine

Golden needles

Vaccines for seniors

Grow up

Can vaccines built for kids work in older immune systems too?

Golden needles

Vaccines for seniors

By Bruce Goldman

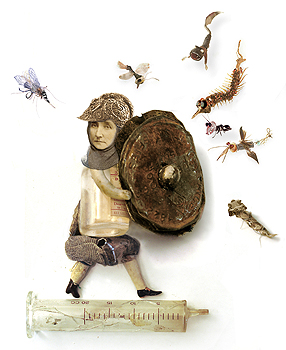

Illustration by Polly Becker

Chalk up at least part of the expansion of life expectancies in developed countries to the advent of childhood vaccinations.

Aided by improved sanitation and antibiotics, vaccines have vastly reduced the toll of infectious diseases, enabling kids to grow up — and, eventually, to grow old.

So it will come as a surprise to many of those grownups that it’s vaccine time again: round two.

The developed world’s success in extending individual life expectancies — from 47 years in the United States at the beginning of the 20th century to 78 now — has allowed people to grow old enough to need a second volley of vaccines. Older bodies’ natural defense systems tend to lose some of their punch, and vaccines can ward off — or at least weaken the severity of — a few diseases capable of inflicting extreme discomfort or worse among otherwise robust seniors.

Not that it’s always easy to convince them this is the case. But Peter Pompei, MD, associate professor of medicine at Stanford, is working on it.

As a geriatric specialist, Pompei doesn’t have to coax any anxious kids into sitting still for yet another unwelcome injection, although he does on occasion encounter resistance of a more articulate sort.

“Recently a woman told me she had gotten the flu from the influenza vaccine,” he says. While Pompei didn’t want to ignore her concerns, he knew her chances of getting an infection from that vaccine were virtually zero. The viral particles that comprise injectible flu vaccines have been killed, so even though they can stimulate immune readiness they can’t cause disease.

But flu-like diseases caused by other viruses are common during the fall and winter months. “When symptoms arise not long after a person is immunized for influenza, there’s a natural inclination to attribute one to the other,” says Pompei.

His suggestion to his patient that some other bug might have given her symptoms just like the flu failed to convince her to get the injection when, as she saw it, she had a very low chance of contracting the flu in the unvaccinated state.

To be sure, these vaccines have their limits, chief among them their inability to fully compensate for the decline in the potency of the aging immune system. Immunology researchers are trying to better understand that decline so they can reverse it or compensate for it by making vaccines that work better in older bodies. In the meantime, clinicians and medical authorities are trying to make the best of the vaccines available right now.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recommend three vaccines for older Americans. The CDC endorses the vaccines — directed at influenza, pneumonia and shingles, each of which represents a greater threat to older people’s than to younger adults’ health — as clearly beneficial and without any notable downside.

It’s not that the bugs that cause those diseases in older people don’t infect younger people. They do. In fact, the chances are extremely high that a 65-year-old in this country has already been exposed to all three: the influenza virus; the bacterium Streptococcus pneumoniae, commonly known as pneumococcus; and the herpes zoster virus, which causes chicken pox and shingles. But these pathogens can be especially nasty, and sometimes deadly, when they manifest in older people.

Forms of these vaccines that are given to children are very effective. How well do they work in older people? The short answer: well enough that, although they could all stand some improvement, health experts virtually unanimously advocate them for seniors.

Just as each disease has its own peculiarities, each vaccine has its own idiosyncrasies, mirroring to some extent those of the disease it combats. The quirks add up to serious PR problems for these vaccines.

Influenza

Virologist Harry Greenberg, MD, the medical school’s senior associate dean for research, who spent a chunk of his career developing flu vaccines, calls flu the Elvis Presley of diseases. “It’s the King,” he says. Year after year, it delivers a major new hit. Influenza attacks pretty much everybody regardless of age, gender, ethnicity or socioeconomic class. Because its symptoms overlap those of many other infectious agents, it’s impossible to cite precise statistics, but the CDC estimates that 36,000 Americans — 90 percent of them at least 65 years old — die annually from infection by the flu virus; about 225,000, likewise mostly past age 65, are hospitalized every year.

The flu shot is covered by Medicare, and in any case it’s cheap and widely available during the flu season — so you’d think everyone would get it. But suspicions that you can get the disease from the vaccine and incredulity about the disease’s danger reduce takers.

Made increasingly aware of the flu’s nastiness thanks to the hectoring of health authorities, who recommend annual vaccinations for everyone over 50, about two-thirds of all Americans past age 65 get vaccinated for it annually. But that means, of course, that one-third of them don’t.

Even if an older person’s immune memory of last year’s flu epidemic were as strong as a young person’s, it wouldn’t help much. Like Elvis changing his costume between acts, the flu virus deftly mutates from year to year. Viral bits recognized by the immune system keep changing shape, rendering last year’s immune response useless against this year’s strain. This leaves vaccinologists perennially scrambling to counter whatever new strain they predict will be lumbering over the horizon in the approaching flu season, which typically starts in late October and peaks in January or February. The vaccine’s efficacy varies from one year to the next, depending on how well-matched the vaccine is to circulating strains. That’s not to say it doesn’t work, just that it works better some years than others.

The odds of getting influenza from the vaccine approximate those of seeing the real Elvis exiting a UFO.

Although the vaccine can trigger temporary fever, malaise and a sore arm in some recipients, overall it’s very safe, because it’s dead. “You will hear many people say that every year they get the vaccine, it gives them a case of the flu. It simply can’t happen,” says Greenberg, the Joseph D. Grant Professor in the School of Medicine, because the form of the vaccine that is given to people age 50 or older is made from killed viruses that are incapable of causing disease. (A newer alternative vaccine administered to people below age 50 is made from an attenuated but nonetheless live virus, Greenberg notes, and could, at least in theory, pose a problem for a weakened immune system.)

The influenza lookalike problem that complicates calculations of its casualties also makes the flu vaccine’s general efficacy tough to ascertain. But studies relying on identification of the influenza virus in patient’s samples rather than guesswork regarding the cause of flu-like symptoms show sizable drops in influenza’s incidence and complications (including hospitalizations and deaths) among vaccine recipients. When there’s a good match between the vaccine and the reigning strain, according to these studies, the vaccine can be as much as 70 to 90 percent effective for healthy seniors.

It’s generally conceded that with advancing age, flu-vaccine efficacy drops — perhaps even to 50 percent for people in the upper age brackets. That’s still a lot better than no efficacy at all, notes Corry Dekker, MD, professor of pediatric infectious diseases and medical director of the Stanford-Lucile Packard Children’s Hospital Vaccine Program. “Granted, the flu vaccine may not be perfectly effective for this population,” she says. “But it’s easily worth the very small risks associated with it.” The risks she’s referring to — a sore arm, for example — are trivial.

Pneumococcus

Pneumococcus, a bacterium that can cause not only pneumonia but also deadly blood infections, meningitis and earaches, normally colonizes our upper respiratory tract, usually without any symptoms at all. Still, pneumococcal disease kills more people in the United States every year — 40,000 or more — than all other vaccine-preventable diseases combined. The majority of deaths are from pneumonia, and the majority of those pneumonia deaths are among seniors.

Older people’s more sluggish immune systems, combined with an age-related decline in the efficiency with which the throat expels microbes, increases older people’s vulnerability to pneumococcal pneumonia, says Stanley Falkow, PhD, the Robert W. and Vivian K. Cahill Professor in Cancer Research in the department of microbiology and immunology. “As your ciliary function decreases, you’re more likely to aspirate these bacteria into your lungs,” he says.

“People tell me, ‘I never get sick, so I don’t need this.’ But it’s an insurance policy.”

Public-health authorities such as those with the CDC unequivocally recommend a pneumococcus immunization for seniors, calling for those over 65 to get a one-time shot, which should be good for the rest of their lives. Like its flu counterpart, the pneumococcus vaccine is covered by Medicare and is often available at the same informal clinics that spring up annually to provide seasonal flu shots. But despite its excellent side-effect profile and its full coverage under Medicare, more than one-third of people 65 and older — and almost half of non-institutionalized 65-plus Americans — report that they haven’t received the vaccine.

This is largely a matter of low public awareness, Pompei says. “People tell me, ‘I never get sick, so I don’t really need this.’ But it’s an insurance policy. You may never get in a car wreck, but you still carry car insurance, because there is a chance that at some point it could happen.”

Every year in the United States, in addition to an estimated 500,000 cases of pneumonia, pneumococcus causes 50,000 cases of bacteremia (blood invasion) and 3,000 cases of meningitis, an infection of the brain’s surrounding membrane. Seniors are most at risk for all of these conditions. Death rates among elderly patients with pneumococcal bacteremia run between 30 and 40 percent.

A staggering number of known pneumococcal strains have been discovered — 92 and counting — each with its own distinctive coat-carbohydrate pattern. Immunity to one strain doesn’t necessarily protect you against any of the others. But a pneumococcus vaccine, composed of complex carbohydrates constituting the bacterial coat, protects against the 23 strains that account for at least 85 percent of all cases of pneumococcal disease.

Attempts to assess the pneumococcus vaccine’s value are plagued by the same kind of ambiguity that dogs efforts to size up the flu shot: Many bugs can cause pneumonia, and the vaccine protects only against those cases that were caused by pneumococcal strains included in the vaccine. Typically, pneumonia patients’ lungs aren’t biopsied — the only sure way to nail the source of infection.

But the circumstantial evidence for vaccination is strong. According to the National Network for Immunization Information, hospital patients who have received the vaccine have a lower incidence of respiratory failure, kidney failure and heart attack; spend two fewer days in the hospital on average; and are (depending on the study) 40 to 70 percent less likely to die than unvaccinated patients.

“At Stanford, we make a concerted effort to immunize as many people as possible who are hospitalized,” Pompei says. “We try to ensure that people who are admitted for other reasons are offered the pneumococcus vaccination, because they’re both a captive audience and a high-risk population.”

Shingles

Shingles, whose formal name is herpes zoster, is the evil twin of chicken pox. Although both rashes are caused by the varicella zoster virus, they occur at either end of the age spectrum with strikingly different symptoms. About one-third of all adults will get shingles at some point, and 10 to 18 percent of those who do will develop a severe pain syndrome — post-herpetic neuralgia. In surveys, about half of those with this nerve inflammation describe their pain as “horrible” or “excruciating.” It can last for weeks or months after the rash itself has cleared up. No effective treatment exists for post-herpetic neuralgia. An additional 10 to 25 percent of shingles patients suffer eye-related complications, such as cataracts.

But the shingles vaccine’s a hard sell.

“There are people who’ve just never heard of it,” says Pompei, “and they ask, ‘Why would I get a shot for something I’ve never even heard of, and I don’t know anything about?’ Unless they’ve known someone who’s had shingles, it’s hard to describe how debilitating it can be. So they don’t want to take foreign proteins into their body. I try to convince them otherwise. I try to explain that even though the likelihood of getting shingles may seem small to them, if it does happen it could be disastrous. The vaccine is a simple, well-tolerated way to reduce that risk.”

“Chicken pox causes an induction of the immune response that lasts for several decades,” says Ann Arvin, MD, the Lucile Packard Professor of Pediatrics, who is a world expert on shingles, professor of pediatric infectious diseases and, with Greenberg, co-director of the Stanford-LPCH Vaccine Program. But the virus sticks around for a lifetime, she says. “Once you’ve been infected, you’re always infected. And the fact is that virtually every adult in the United States was infected with chicken pox in childhood. The virus is inside of you, and you’d better have some immunity or it will reactivate. But there’s an age-related decline in immunity beginning at around age 45 or so and continuing year by year after that. So people are susceptible to their own virus reactivating.”

As your immune system lowers its guard, the virus particles, which have been holing up near the spine in sensory nerve cells, work their way down these cells’ long arms to the skin, causing the painful rash known as shingles.

Deaths from shingles are rare, but severe consequences aren’t. Post-herpetic neuralgia, an exquisite sensitivity to touch, long outlasts shingles’ characteristic skin rash. Even friction from light clothing or air blowing across the skin can induce intense pain.

A study Arvin published in 2002 established proof of principle that an existing vaccine for chicken pox could prevent shingles outbreaks in individuals with compromised immune systems. Later on, a huge study involving more than 38,500 healthy people age 60 or older showed that a vaccine composed of the same weakened viral strain that was in the children’s chicken pox vaccine — but administered at a dose at least 14 times higher — cut the number of shingles cases by more than half and, just as important, dropped the incidence of post-herpetic neuralgia by a full two-thirds. While this vaccine, approved by the FDA in 2006, was considerably less effective in protecting the very oldest study participants from getting shingles, it retained most of its ability to shield them from the extreme pain of post-herpetic neuralgia.

According to a 2007 CDC survey, only 1.9 percent of those who should get immunized for shingles do. This is partly due to the vaccine’s relative newcomer status, which means physicians are less familiar with it so are a bit less likely to recommend it, says Gina Mootrey, MD, associate director for adult immunization at the CDC. It’s also partly because the CDC recommends it for people as young as 60 — five years before Medicare kicks in. Some private plans don’t cover the otherwise pricey shot, whose uninsured price runs in the low triple digits.

Better safe than sorry

Even in the case of influenza and pneumococcus vaccines, the CDC would like to see vaccination rates rise from today’s approximately two-thirds of the 65-plus population to more like 90 percent, although it has no plans to increase the current outreach efforts. “One of the reasons we hear most often for people not being vaccinated is that they didn’t know they needed the vaccine,” says Mootrey, who recommends that seniors ask about their vaccination status at every doctor visit.

Nowadays, researchers are broaching the possibility of vaccines for many diseases of aging — not only infections, but cancer, heart disease and Alzheimer’s. Although a couple of promising vaccines are in late-stage clinical trials for certain classes of cancer, most of immunologists’ vaccination dreams are still years from realization. So, while we’re waiting, we should take advantage of the vaccines we have. With full vaccination, tens of thousands of seniors would live longer and thousands more would be spared needless pain. Over 65? Roll up your sleeve, please.

Related story:

What to do when immunity wanes

One straightforward tactic is the “multiply and conquer” method.

Simply upping the chicken pox vaccine’s dose yields a product that’s effective against shingles — the adult disease caused by reactivation of the same virus.