SPRING 2009 CONTENTS

Home

The demonization of immunization

Shots get the once-over

What is a vaccine?

Immunization demystified

Asking How

Vaccine Side Effects Probed

When science gets hijacked

NBC News chief medical editor tells why she broke her silence

Insourced to India

A vaccine for a scourge of the developing world

Peet’s passion

The medical education of Amanda Peet

Field yields

Can genetically engineered plants provide vaccines?

Shoot it, donít smoke it

An injectable tobacco-grown vaccine

Golden needles

Vaccines for seniors

Grow up

Can vaccines built for kids work in older immune systems too?

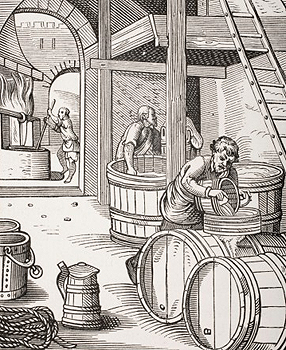

Lager heads

Geneticists chart the evolution of beer

By Krista Conger

Art by Jost Amman (created 1568)

It all started with some unhappy Bavarians.

It was 1553 and, dissatisfied with the sour, medicinal taste of ale brewed in the summer, the ruler of Bavaria, Duke albrecht v, restricted brewing to the cooler months — from Sept. 29 (St. Michael’s Day) to April 23 (St. George’s Day). What they wanted was consistently good ale. What they got was a brew of a different sort: the first-ever lager.

What happened? The cold inhibited the traditional ale yeast and fostered the rise of a mixed-breed yeast fortified with DNA from a second species, better adapted to winter conditions. Once the new strain arose, the Bavarians encouraged it further by reusing the same barrels to brew batch after batch. Gone was ale’s trademark cloudy fruitiness, replaced with a clear, crisp bite.

Now a few hundred years later, scientists have investigated the resulting genetic mélange. Gavin Sherlock, PhD, a Stanford assistant professor of genetics, and Barbara Dunn, PhD, a senior research associate, studied 17 lager yeast strains from Europe and the United States. After much sampling (of the yeast!), they determined that the DNA mixing occurred not once, but twice, creating two distinct hybrid lineages.

One player, commonly known as baker’s yeast, has been used for thousands of years to make both bread and ale. It grows best between about 85 and 90 degrees. The other, which also hung around near breweries in the Middle Ages, grows best at 70 to 75 degrees and can tolerate even colder temperatures. Each partner brought specific, unique advantages to the match.

“Yeast generates hundreds of by-products during fermentation and can greatly influence the flavor of the beer,” says brewer and beer writer Horst Dornbusch. For example, the typical banana, clove and bubblegum taste of wheat-based beer is due to the strain of yeast used in fermentation, not, as many believe, the switch to wheat from barley.

Sherlock and Dunn traced the spread of the progeny across Europe, marking which genes were kept and which were lost through the centuries. The research, recently published in Genome Research shows that one lineage is associated primarily with Carlsberg breweries in Denmark and others in the Czech Republic and Slovakia, while the other strain localizes to breweries in the Netherlands, including Heineken.