The hitch with the breast cancer marketing pitch

By AMY ADAMS

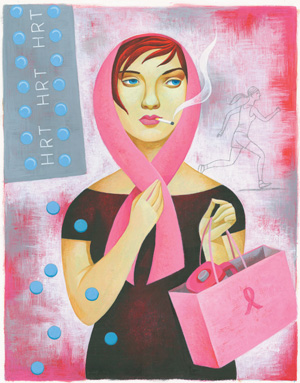

Jody Hewgill |

|

|

|

Women living in the San Francisco Bay Area have a risk of breast cancer that’s 15 percent higher than the national average, and it’s mostly because of women like me. Sure, we try to be health-conscious. We eat our organic produce and hike the coastal trails regularly.

But where our breasts are concerned nothing can overcome all those years spent in school, shunning motherhood in favor of a bright and illustrious future career.

Or at least an interesting career. And one that covers the cost of those organic vegetables.

As with many women living in areas with a high breast cancer risk, including the San Francisco Bay Area, Seattle, Hawaii, and west Los Angeles, the decisions that allow me to live in this high-priced locale have had some health consequences. If some studies are to be believed, holding off on kids until age 35 raised my risk of breast cancer. Add to that a hearty enjoyment of the area’s vinicultural bounty to the tune of a drink or so a day (with that “so” being closer to two than zero) and those same studies suggest my risk is pushed up even more.

Related News

Knowing what I do about my higher-than-average breast cancer risk, I have a choice to make if I want to avoid the disease. I can: a) take steps to put a cap on my increased risk; b) donate money to the cause and hope they find a cure; c) stock up on pink-ribbon-emblazoned products as a talisman against the disease, or d) do all of the above, because you just never know.

So far I’ve chosen “a.” I’ve tried to push back my risk by breast-feeding as long as possible, hauling around a ball and chain in the form of a breast pump to and from work and everywhere else I went, including Italy (not that I’m bitter) for the first year of my children’s lives. Maintaining a healthy weight, exercising and not smoking also lowers my risk.

But why not be inclusive and choose “d”? Would a house full of donation thank yous and pink appliances help stave off breast cancer? As the most common cancer in women, donations made through a new set of pink golf clubs could one day help me or someone I love. Right?

Seeing the relentless advertisements for pink awareness has got me wondering if I’m missing out. Should I stock my kitchen with a pink blender, travel with a pink microfiber towel, write reminders to myself on special edition pink ribbon Post-It notes, freshen my breath with pink Tic Tacs or even tweeze my ever-burgeoning supply of chin hair (thanks kids!) with a set of pink tweezers — all of which provide small amounts of money to the cause? Well, donating to breast cancer research directly or through pink products might feel good and could lead to treatments for breast cancer — but it won’t reduce my chances of getting the disease.

As for those pink products, here’s one tidbit that gets me thinking about who benefits. When 3M made a 70-foot-tall pink ribbon entirely of Post-It notes in 2004 and put it on display in Times Square for breast cancer awareness month, it spent $500,000 building and promoting that public art project. The company’s sales increased 80 percent over expectations thanks to the publicity, of which 3M gave only $300,000 — about half the cost of the campaign — to breast cancer research.

Am I alone in thinking those numbers don’t add up to a corporate culture that’s concerned about me and my health? In fact, it’s part of a new strategy called “cause-related marketing.” Basically, it goes like this: Appear to care. People will like you better. They’ll buy your products. Corporate profits will rise. Shareholders are happy. Although the term emerged in the 1980s, it is born out by a 2006 study finding that nine out of 10 people would jump to a new brand if they liked that company’s cause affiliation. As one of the most supported causes, breast cancer is seen as a sure win for many companies.

In response to what it sees as misdirected spending on the part of women, the San Francisco-based Breast Cancer Action organization has been running its Think Before You Pink campaign during breast cancer awareness month to draw attention to the pink marketing tactics. Its point is that companies are doing more to improve their bottom line than to prevent breast cancer. BCA believes that a pink show of support is nice, but a direct donation to a breast cancer organization, such as BCA, would go a lot further.

It irks BCA director Barbara Brenner that companies come off looking so good when they do so little. “Women are being encouraged to buy something rather than do something,” she says. In some cases the companies promoting breast cancer awareness might actually be doing harm. She points to BMW, which gives $1 per test drive during the month of October to breast cancer research. That same test drive spews toxins into the environment that, even if they don’t contribute directly to breast cancer, certainly aren’t a net health positive. Or there’s the bottle of Sutter Home white zinfandel that earns $1 for breast cancer research with each purchase. That’s despite the fact that alcohol increases breast cancer risk.

Hey, I’m not pointing any fingers here. I like a glass of wine as much as the next woman. But donating to a breast cancer cure through purchases that increase my risk of breast cancer seems like a questionable strategy.

Brenner’s take on what should be done to prevent breast cancer is more expansive than mine. Me, I’m all about what I can do for myself. Breast-feeding, eating well, running. Brenner, she cares about other people, too. That’s why she’s an activist and I’m just in really good shape. She feels that our society is set up to force us into cars, to eat bad food and to be exposed to environmental toxins. “Most of the prevention focus is on personal responsibility issues, telling women that if they just made better choices they wouldn’t get cancer. I want to change society so that you have to get exercise and encounter fewer environmental hazards.”

Basically, instead of encouraging every woman to go out of her way to find healthy food choices, get exercise or avoid toxins, she’d like to see those health-promoting choices be a normal part of society.

That’s an idea that, in a scaled back format, has also occurred to Christina Clarke, PhD, who is an epidemiologist with the Northern California Cancer Center in Fremont. Clarke is hoping to reward companies for putting their policies where their pink-ribbon profits are. She and her colleague at the NCCC, Pamela Priest Naeve, want to develop a “pink ribbon worthy” designation for companies that support breast health.

“If you affiliate your company with the breast cancer cause to your customers then you should be consistent with your employees,” says Clarke, who is also a consulting assistant professor in health research and policy at Stanford and a member of the Stanford Comprehensive Cancer Center.

On the list of what makes a company worthy would be having healthier snacks available on site, helping employees get exercise, encouraging longer breast-feeding with decent maternity leave and an appealing space for nursing mothers to pump, as well as enacting policies that support women who are undergoing breast cancer treatment. These might include leave time for cancer treatment and flexible hours when women initially return to work.

Clarke’s take on breast cancer awareness and prevention comes from many years spent investigating the causes of breast cancer. At the NCCC she has access to raw data on all new cancer cases in counties surrounding San Francisco. The organization is tasked with collecting that data as part of the state-mandated California Cancer Registry intended to track the rise and fall of cancer within the state. The NCCC contributes this cancer data to a national registry orchestrated by the National Cancer Institute.

Using that information, epidemiologists at the NCCC have been at the forefront of piecing together who gets cancer and why. Although what they and others have found so far accounts for less than half of breast cancer cases, Clarke says she wishes people would take the known precautions in addition to funding other causes through pink purchasing, direct donations or participating in fundraising athletic events.

Clarke’s not arguing that all women should have kids at 19 to lower their risk of breast cancer; as someone who also looks back with a weary sigh on her days trucking around her own breast pump, she knows breast-feeding isn’t always easy. However, she also points out that no amount of walking or shopping for a cure will mitigate the effects of, say, smoking or being overweight.

Clarke says that if I or other women are already eating well, exercising and otherwise taking care of our breast health and are looking for additional ways to be involved, we should consider responding to surveys and participating in research. Some of the money that starts out as a donation or a well-intentioned purchase goes to organizations such as Komen for the Cure, among the largest recipients of pink ribbon campaign funds and which recently awarded $82 million in breast cancer research grants. Of that money, some of it goes to researchers like Clarke, who need both healthy women and those with breast cancer to talk about their lifestyle. But many women aren’t talking. Ironically, women are making donations and funding research that is lagging because they won’t participate.

“My sense is that we are bombarded with junk mail, spam and phone calls, and research requests get lost in all that. People are just fed up,” she says. Because of that, it’s hard for Clarke and her colleagues to get the answers that women need. “Maybe women think they’ve done their part by giving money to research, but they don’t understand that we also need them to participate in that research.”

All of this is more than just food for thought as I run off my disease risk. With two kids and that writing job that kept me in school all those years, time is one thing I don’t have in abundance. And with the mortgage that comes from living close to interesting work, a scattershot approach to breast cancer spending is out.

That brings me back to options “b” through “d.” Direct donations might be an option to organizations that use all of that money to prevent and understand breast cancer. But for now, pink ribbons aren’t for me. If I want the most breast cancer bang for my buck, I’ll spend that money on running shoes and organic apples instead.

That, and from now on I’ll answer when Christina Clarke or other researchers come knocking.

Comments? Contact Stanford Medicine at