|

|

Dear Readers,

Remember the 1970 rock anthem War? The lyrics asked the question: “War, what is it good for?” “Absolutely nothing,” came the reply. Along with many other songs and anthems, it caught the anti-Vietnam War spirit of the time. But is its message valid?

History shows that war has indeed advanced medicine, at least in some areas. For example, the critical matter of protecting soldiers from infection during World War II inspired the U.S. military and pharmaceutical industry to find a way to mass-produce penicillin. Before 1942, antibiotics were just being discovered and not yet part of the clinical armamentarium.

The use of radar served as a prototype for ultrasound technology, and even some of the chemical poisons used during WWII served as the foundation for modern cancer chemotherapy. The need for speed in treating battlefield injuries has brought medical innovation to soldiers — and to civilians: Gunshot victims benefit from techniques learned by battle surgeons.

It’s easy to find examples of medical spin-offs from wartime, but I personally believe the lyrics of that antiwar song are inherently true. War is good for nothing. Of course, I acknowledge that some situations, e.g., Adolf Hitler’s rise, demand war. But as a physician who has focused on helping children who face catastrophic disease, I find it abhorrent to observe children and families suffering from war’s consequences. Indeed, one might have hoped that our civilization would have evolved beyond the indiscriminate violence that is increasingly the face of war today. As a child I believed that war should be fought directly by the national leaders calling for it. In practice, this admittedly naïve fantasy might have saved countless lives.

In the modern era, casualties to innocent civilians have been tragic. The war in Iraq is a case in point. Though estimates vary, it’s apparent that hundreds of thousands of additional deaths have occurred among Iraqi civilians since the war began.

I recognize that war can drive physicians to brilliant achievements and great acts of humanity on the battlefield and in military hospitals. Yet, deeply concerning to me is the shadow war casts by creating circumstances that set physicians on a collision course with the ethics of our profession.

Consider the troubling role of doctors in the treatment of Iraqi prisoners. When evidence of the U.S. military’s use of torture emerged from Abu Ghraib prison, I was disheartened to learn that a number of physicians failed to uphold their professional obligations and make public the atrocities.

Part of the problem is the Bush administration’s narrow definition of torture, which at one time held that only acts resulting in “organ failure, impairment of bodily function, or even death” constitute torture punishable by law. I gained further insight from M. Gregg Bloche, MD, JD, a law professor at Georgetown University who has investigated U.S. military physicians’ involvement in torture at Guantanamo Bay in Cuba. In his July 7, 2005, New England Journal of Medicine article he writes: “…psychiatrists and psychologists have been part of a strategy that employs extreme stress, combined with behavior-shaping rewards, to extract actionable intelligence from resistant captives.” Their role was to provide interrogators information about prisoners’ physical and psychological soft spots.

It’s dangerous — to medicine and society — for governments or physicians to violate medical ethics during conflicts or war. War is unquestionably bad for health. But if the contract between the doctor and the patient remains intact, the integrity of the medical profession can be sustained despite the ravages of war.

With best regards,

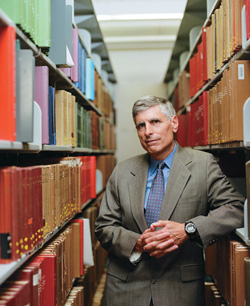

Philip A. Pizzo, MD

Professor of Pediatrics and of Microbiology and Immunology

Carl and Elizabeth Naumann Professor

Dean, Stanford University School of Medicine