Activists say Hollywood is blowing smoke about movie ratings

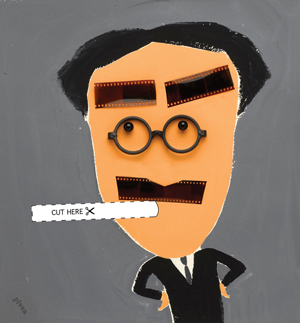

Hanoch Piven |

|

|

|

By BRIAN LEE

The battle over R ratings for films with smoking continues to smolder despite Hollywood’s concession to anti-smoking advocates this summer.

Though the Motion Picture Association of America agreed to consider smoking alongside foul language, sex and violence in setting film ratings, that’s not enough, the advocates say.

“The MPAA pretended to solve the problem,” says Stanton Glantz, PhD, a professor of medicine at the University of California-San Francisco who spearheaded the initiative. “The good news is that they were forced to recognize a real problem. Now there are a lot of people expecting to see a real solution,” says Glantz, a Stanford School of Engineering alumnus and former cardiology fellow.

R ratings for smoking would save children’s lives, he says: “The science clearly shows that the more smoking in movies kids see, the more likely they are to take up the habit.”

According to a 2001 study in the Lancet medical journal, more than 85 percent of the top 25 U.S. box-office films from 1988-97 contained tobacco, and during that same period, 32 percent of PG-13 movies included branded cigarette appearances. Also in 2001, Glantz started the Smoke Free Movies campaign to stop the movie industry from promoting tobacco to children. Anti-smoking activism had captivated Glantz since his epidemiological research in the ’90s identified secondhand smoke as a cause of heart disease and the third-leading preventable cause of death.

“Stan really understands how to translate science into public health gains. I would say he founded the movement,” says James Sargent, MD, associate professor of pediatrics at the Dartmouth-Hitchcock Medical Center and co-author of the 2001 Lancet study and another landmark Lancet study in 2003. That study, which followed 2,600 adolescents for up to 26 months, found that teens who watched more movies with smoking were more likely to light up.

Glantz’s group has fought to slap R ratings on all new movies with smoking. The initiative took out full-page ads in the New York Times and Variety to help raise public awareness. The campaign fuels grassroots activism by urging letters to the MPAA, Congress, state prosecutors, film studios, movie stars and local theaters. Glantz keeps on the pressure by testifying before Congress and meeting with members individually.

The science prompted the attorneys general from 41 states to send letters to the MPAA in 2003, 2005 and 2006 requesting action to prevent youth smoking. Physicians also put on the pressure. In 2005, Stanford doctors and Lucile Packard Children’s Hospital pediatricians sent entertainment executives 300 flattened cigarette cartons scrawled with notes from children, community members and medical school faculty demanding that kid-rated movies be cigarette-free.

It seemed likely change was coming when in October 2006, MPAA president Dan Glickman asked for recommendations from the Harvard School of Public Health and in February was advised by the researchers to eliminate smoking in films accessible to youth.

Then in May the MPAA announced its new policy — falling short of Harvard’s advice. And in July the Walt Disney Co. announced that new Disney family movies will show no smoking. “So far, these policies have made little difference,” says Glantz.

On Glantz’s Web site (www.smokefreemovies.ucsf.edu), parents can find a list of current smoke-free movies as well as steps on how to pass and publicize local council resolutions supporting action. “Hollywood should just stop making youth-rated films that promote smoking,” he says.

Comments? Contact Stanford Medicine at