The great surgeon's legacy lives on through those whose lives he touched

|

|

By RUTHANN RICHTER

The father of heart transplantation, Norman E. Shumway, MD, PhD, died Feb. 10 at his Palo Alto home of complications from cancer at 83.

One of the pre-eminent heart surgeons of our times, Shumway, professor emeritus of cardiothoracic surgery, nearly didn’t become a doctor at all.

When the Kalamazoo, Mich., native entered the University of Michigan in 1941, he had intended to study law. But two years later he was drafted into the Army and took a medical aptitude test that changed his course. The test asked him to check a box for a career interest: medicine or dentistry. He chose the first and was enrolled in a specialized Army program that included pre-medical training at Baylor University in Texas.

The choice had momentous consequences: Shumway went on to perform the first successful human heart transplant in the United States, in 1968 at Stanford. The recipient, 54-year-old steel worker Mike Kasperak, lived for 14 days.

The landmark operation created a burst of enthusiasm for heart transplantation, though cardiac surgeons quickly lost interest because of the high rate of post-surgical deaths.

Related story: |

|||||

Shumway nonetheless persevered in the field amid controversy over legal and economic issues, particularly the issue of what constitutes brain death among potential donors. For nearly a decade, Stanford stood virtually alone as a center for performing the pioneering operation. Shumway and his colleagues made steady progress, paving the way for a procedure considered routine today.

Nearly 60,000 patients in the United States have enjoyed longer lives because they received new hearts through transplant programs at some 150 medical centers around the country. At Stanford, some 1,240 patients have benefited from heart transplants.

|

|

| Shumway and Donald Harrison, MD, meet the press after performing the first U.S. adult human heart transplant. |

Shumway, a reticent man who did not like to tout his accomplishments, told a crowd of transplant patients at a 2003 Stanford reunion that it was “gratifying to see the changes that have made this (heart transplant) an almost ordinary experience.” At the reunion party, which also marked his 80th birthday, he praised the patients, saying, “You made us look good.” He called them “the real heroes … so marvelous, so strong, so courageous.”

Philip Pizzo, MD, dean of Stanford School of Medicine, called Shumway “one of the 20th century’s true pioneers in cardiac surgery.”

“He developed one of the world’s most distinguished departments of cardiothoracic surgery at Stanford, trained leaders who now guide this field throughout the world and created a record of accomplishment that few will ever rival. His impact will be long-lived and his name long-remembered,” Pizzo says. “We will miss Norm Shumway and the dignity and excellence that he brought to medicine and surgery — and to Stanford.”

|

|

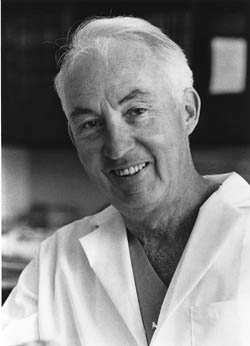

| Shumway checks on a patient. |

Shumway, the Frances and Charles Field Professor of Cardiovascular Surgery, Emeritus, cherished the fact that he had trained so many of the world’s leading cardiac surgeons. His approach, contrary to the conventions of the time, was to step back from the spotlight and give his young trainees major responsibility in the operating room, greatly improving the learning experience.

“I never worked so hard in my life and never learned so much and had so much responsibility at a young age,” says William Brody, MD, PhD, president of Johns Hopkins University, a Shumway trainee. “He was a brilliant teacher and a master psychologist. With his humor, he always made it fun. To be in the operating room with Shumway was the height of your day because he was brilliant and witty. At a time when everybody made cardiac surgery seem complex, he made it seem easy.”

Shumway did his internship and residency at the University of Minnesota, where he became fascinated by cardiac surgery. After another two-year stint in the military, this time with the Air Force, he continued his surgical training in Minnesota and obtained his PhD in cardiovascular surgery in 1956.

He came to Stanford in 1958 as an instructor in surgery. Shortly after his arrival, the medical school moved from San Francisco to Palo Alto, giving Shumway the opportunity to launch the cardiovascular surgery program at the new, expanded campus.

In 1959, working with then-surgery resident Richard Lower, MD, he transplanted the heart of one dog into another. The transplanted dog lived eight days, proving it was technically possible to maintain blood circulation in a transplant recipient and keep the donated organ alive. Shumway and his colleagues spent the next eight years perfecting the technique in dogs, achieving a survival rate of 60 to 70 percent.

|

|

| Bruce Reitz, MD, (left) and Shumway perform the world's first successful combined heart-lung transplant. |

“We started out doing this as a technical exercise, and the animals began to survive,” he said years later.

In 1967, he announced that he was confident enough in the research to start a clinical trial and that Stanford would perform a transplant in a human patient if a suitable donor and recipient became available. Shortly thereafter, Christiaan Barnard, MD, of South Africa performed the world’s first heart transplant on a patient who lived for 18 days, using the techniques Shumway and Lower had developed.

On Jan. 6, 1968, Shumway performed his landmark first procedure which — to his chagrin — attracted worldwide media attention, with journalists climbing the walls of the hospital, trying to get a peek into the operating room.

Years later, Shumway said of the transplant: “We put in the heart and nothing happened. There were slow waves on the EKG and then the heart began beating stronger and then, exuberance…. We knew we would be OK.”

Edward Stinson, MD, then chief resident in cardiac surgery who assisted Shumway, describes the operation as awe-inspiring. “After we removed the recipient’s heart, we stared at the empty pericardial cavity and wondered what we’d actually done,” recalls Stinson, professor emeritus of cardiothoracic surgery at Stanford. “His (Shumway’s) wit always came through, no matter how challenging the circumstances. He said, ‘I’m not sure. Time will tell.’ We proceeded with implanting the new heart. It was pretty exciting to see it start up.”

Shumway and his colleagues progressed steadily over the next decade through careful selection of donors and recipients, increasing the donor pool, improvements in organ preservation and in heart biopsies, and advances in drugs to prevent rejection of the foreign organ, among other developments. His team was the first to introduce cyclosporine for heart transplantation in late 1980. With use of the immunosuppressive drug, the field took a giant leap forward.

The Shumway family asks that any memorial donations be made to the Stanford University Heart Transplant Patient Care Fund, in care of the Department of Cardiothoracic Surgery, 300 Pasteur Drive, Falk Building, Stanford, CA, 94304-5407. |

|||||

In 1981, Shumway and Bruce Reitz MD, the Norman E. Shumway Professor of Cardiothoracic Surgery, performed the world’s first successful combined heart-lung transplant in 45-year-old advertising executive Mary Gohlke, who lived five more years and wrote a book about her experiences. By the late 1980s, they were transplanting hearts into infants as well.

Shumway rose to become chief of the division of cardiothoracic surgery at Stanford in 1965; in 1974, he negotiated the creation of a separate Department of Cardiothoracic Surgery, which he chaired until his retirement in 1993.

His accomplishments were not limited to the field of transplantation. Shumway also made significant contributions to treatment of congenital heart problems in children, as well as valve problems and aneurysms in adults.

Over the years, Shumway received dozens of honors and awards. In 1980, he was named honorary president for life of the International Society of Heart and Lung Transplantation. He also received the Scientific Achievement Award from the American Association for Thoracic Surgery, the American Surgical Association, and the American Medical Association, as well as the Trustees Medal for Distinguished Achievement from Massachusetts General Hospital, to name a few.

Remembering Norm Shumway

Excerpts from an online memory book

Dozens of the great man’s admirers posted condolences and memories at mednews.stanford.edu/shumway/guestbook/.

A sampling follows:

I came to pediatrics at Stanford as a brand new graduate nurse in late 1966 when, after three days of orientation (!), I was assigned to nights as the only RN on peds. To say I was young, stupid and terrified gives me more credit than was due. A little after midnight, this smiling guy in rumpled scrubs strolled in and asked me who I was, what was going on and how the kids were.

I rather tearfully replied that there were these four kids who had heart surgery and were on monitors that I had no idea how to work and was afraid something bad would happen and....

He smiled, escorted me to the room, gave me a 20-minute crash course in the basics with lots of laughs thrown in, walked out on the patio, brought in a lawn chair and stayed there with me until morning. I had no clue who he was, and I did not care because he clearly cared about those kids and about me.

That is the Norman Shumway I knew for the next several decades, mostly from afar. Kind, professional, caring, funny, dedicated and a real gentleman. His passing made me cry and laugh at the memories much like that first night. — Cele Quaintance, RN

_______

Goodbye, Dr. Shumway. You inspired hundreds of young physicians by your optimism and confidence in their future. There is always room at the top, you said. There was room, because you believed in our potential. We are sad because we doubt we will ever meet anyone like you again. We are thankful because you will always be with us in our memory. — William Nolan, MD

_________

I am deeply saddened by the news of Dr. Shumway’s death. He holds a very special place in my heart — which functions because of him and the grace of God. In 1972 my pediatric cardiologist, Dr. Marvin Auerback, was playing tennis with Dr. Shumway and asked if he would be willing to take a look at a young girl with transposition of the great arteries.

Dr. Shumway took a chance on me and performed what would become life-saving cardiac surgery. I have wonderfully fond memories of his gentle, humorous spirit and of him playing with my “Mrs. Beasley” doll every time he came to see me. I am grateful for his tenacity and for not giving up when my prognosis did not look so good. I now serve as a hospital chaplain and teach in a program that trains chaplains. My work is profoundly motivated by my experience at Stanford and Dr. Shumway. May God bless him and keep him. — Susan Roberts (“Susie”)

Comments? Contact Stanford Medicine at