America veering toward theocracy

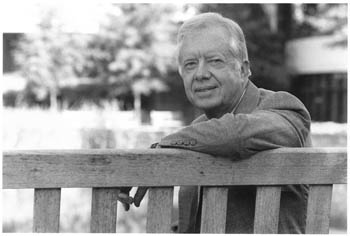

Rick Diamond |

|

|

|

Since leaving office, Jimmy Carter has dedicated his life to the pursuit of justice and equal rights around the globe. The 2002 Nobel Peace Prize winner uses the Atlanta-based Carter Center as the hub for his humanitarian pursuits.

The 39th president of the United States is the author of more than 20 books. His latest, Our Endangered Values, America’s Moral Crisis (Simon & Schuster, 2005), details his concerns about the threat religious fundamentalism poses to America’s values.

Paul Costello, executive director for communication and public affairs at the School of Medicine, spoke recently with the former president about religious fundamentalism, evolution and Carter’s belief that the United States is spiraling toward theocracy. Costello was a press spokesman for First Lady Rosalynn Carter during her White House years.

Good morning, Mr. President. I want to begin by asking you about your religious beliefs. You were a nuclear engineer who studied advanced physics. At the same time you’re a committed Christian. Yet scientists are more likely to be agnostics or atheists than the average person. What sustains your belief in God?

Carter: I don’t have a doubt about my faith in God as the ultimate creator of the universe — and so I’ve never had the problem that some have had. I find no incompatibility between the existence of a supreme creator and discoveries that human beings have made through our own intelligence, that God’s given us. I think that God, the creator, has given human beings an ability, maybe even a responsibility or obligation, to learn all that we can about our own existence.

Your latest book, Our Endangered Values, describes the great harm inflicted on our nation by Christian fundamentalists, giving repression of women as one example. Is science also under threat in this new era of Christian fundamentalism?

Carter: I don’t think there is a restraint on the advanced scientists in the realm of microbiology or astronomy or chemistry or other physical sciences, no. But it does mean that a large number of American schoolchildren, certainly in the elementary and secondary schools and, to some degree, certain colleges, are being deprived of effective science classes.

What’s behind the significant shift toward fundamentalism around the world? What do you think is the catalyst there?

Carter: I think part of this is caused by globalization, by instant communications, by doubt and uncertainty. As a result, you’re required to look at the nuances of complex subjects, at both sides of issues. It pushes people to say, “Some of the things I believe might have to be modified because they are mistaken, and other people might know more.” This is a very difficult thing for certain people to accept, and they revert back to self-assurance: “I cannot be wrong. God is on my side. Anyone who disagrees with me must be mistaken — and inferior.”

You have said that America is moving toward theocracy.

Carter: Yes. I did. I don’t think there is any doubt about it. The elements of fundamentalism have been extant for centuries. I think lately it has become more prevalent, mostly originating with the Southern Baptists, but that is not the only group. As this is happening, the separation between church and state has been broken down. Religious voices are becoming increasingly dominant in Washington.

The origins of this debate are both secular and religious. Thomas Jefferson actually said that we should build a wall between church and state. And Jesus himself stated, “Render unto Caesar the things that are Caesar’s and to God the things that are God’s.” To me, this justifies the separation of the two.

Some politicians claim that their run for office is divinely directed. They also claim that their faith encourages them to take certain actions as civil servants. What role did your faith play in the execution of your duties?

Carter: Well, about the implication that God has anointed a particular human being in public office: It embarrasses me. And the favoring of a particular religious faith by a president or public officials, to me, is contrary to my basic beliefs.

For the most part, my secular duties as president were compatible with my Christian beliefs. But on very rare occasions, as a Christian, I had some conflicts. I’ve never felt that Christ would have approved of abortion on demand. So I’ve thought abortion should be avoided if possible. I’ve always thought that abortions result from a series of human errors and tried every way I could to minimize them. Yet the Court ruled under Roe v. Wade that it was permissible in the first trimester. I took an oath to uphold the law as ordained by the Supreme Court and I did so.

You write that scientific knowledge has never threatened your religious faith, and point to a Bible verse that has fortified you since childhood: “Now faith is the substance of things hoped for, the evidence of things not seen.” What does this verse mean to you?

Carter: Yes, it’s in Hebrews, I think. It is a definition of faith itself. I don’t have to have faith to know that a ball is round. I don’t need faith to know that the desk that I’m sitting behind is firm and hard, and so forth. Faith comes when you have beliefs that you cannot prove, feel or touch or see. I can’t see God or prove God. I have not seen Christ walking through the roads in the Holy Land. But I have faith that Jesus Christ lived as the son of God and that he’s the epitome of proper human behavior. I think the verse is ultimately succinct and clear. Faith is a thing that you cannot see, but you still believe.

Why are so many Americans suspicious of evolution?

Carter: Some people cannot accept that any word in the Scripture could possibly be mistaken. Some, including some in my own church whom I teach every Sunday, have a very devout belief that the world was created by God in 4004 B.C. in maybe six calendar days. I never had any problem accepting the fact that the Earth is billions of years old and that it revolves around the sun rather than the other way around, but I don’t see a need to argue with my church members about it.

One of the significant breaks between fundamentalists and scientists seems to be the notion that human beings and apes evolved from a common ancestor.

Carter: There is an aversion on the part of proud human beings to attribute our origins to what we consider a lower animal. I think that it is a matter of lessening the assessment of God-like attributes to a human being — that I am a little less than an angel.

As a Nobel Peace Prize winner, what do you think the chances are of brokering this conflict?

Carter: Well, I’ve tried. But I think that the two extremes, at least, are incompatible. There are some scientists, as I think you pointed out, who are either agnostics or atheists. They don’t want to face such a thing as a supreme being or standards that are imposed on us by a superior entity. There are others, mentioned above, who take Scripture literally. Those two extremes are incompatible.

I have written poems about it and I have written theses about it. I’ve made speeches about it. I teach in my Sunday school lessons about it. And the main point is that there is no incompatibility between science, on the one hand, and my religious beliefs, on the other hand.

Comments? Contact Stanford Medicine at